One day recently I was discussing yoga with my son via text message. Despite the obvious dissonance, it was a good conversation, and mostly amounted to my saying I was looking forward to getting home from work so that I could do some. Yoga, that is. He told me about the poses he was doing and asked a simple question: Do you take a little time for yourself when you’re done?

I said yes, without really thinking of the implications of the question. Yoga itself, it seemed to me, was already taking a little time for myself. So of course, I was doing that. What he was asking, I realized as I thought about it later, was if I go straight from that time into some other busy distraction or if I sit in it a while. If that’s what he meant, then the answer was no.

And so I have changed that. Yoga is a relatively new practice for me and one that I am stretching into. (See what I did there?) Since that conversation, I’ve made small changes to the routine. After trying to move my body into the outlandish positions the guy in the beginner yoga video on YouTube is showing me, I read a couple of poems. I make tea. I take my time and take a few more deep breaths, trying to make them sound like the ocean like the guy told me to because it’s apparent that in all of my fifty-some years I’ve never learned to inhale and exhale properly. I mumble namaste to myself.

It’s ritual. The importance of repeating a practice, with intention, made itself known to me a few years ago. I don’t engage in great ceremony, but I do practice small rituals daily, or nearly so. The yoga is too new to carry much history for me. The poems and the tea, on the other hand, go further back. The scent of a particular black tea calls up pleasant memories. The scent of a particular green tea reminds me that what I am doing intends to tie mind and body together in a healthier relationship.

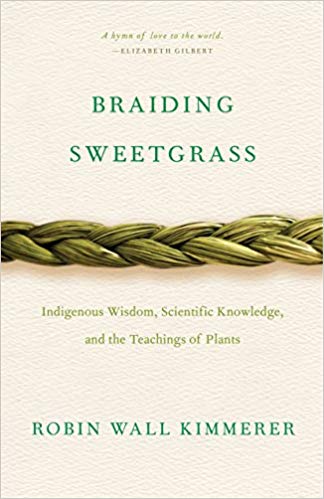

Robin Wall Kimmerer writes in Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants of the ritual and ceremony surrounding this sacred plant, saying “Breathe in its scent and you start to remember things you didn’t know you’d forgotten.” She recalls the teaching of her people’s elders that “ceremonies are the way we ‘remember to remember.'”

She writes of a friend, Wally “Bear” Meshigaud, who uses sweetgrass as a ceremonial firekeeper. Normally, there are those who provide the sweetgrass to him, but at times he doesn’t have enough. “At powwows and fairs you can see our own people selling sweetgrass for ten bucks a braid. When Wally really needs wiingashk for a ceremony, he may visit one of those booths among the stalls selling frybread or hanks of beads. He introduces himself to the seller, explains his need, just as he would in a meadow, asking permission of the sweetgrass. He cannot pay for it, not because he doesn’t have the money, but because it cannot be bought or sold and still retain its essence for ceremony.”

In the meadow, he asks permission of the sweetgrass to be used in his ceremony. In the way of his traditions, he ascribes (or rather, assents) to the earth its autonomy. Kimmerer writes, “Sweetgrass belongs to Mother Earth. Sweetgrass pickers collect properly and respectfully, for their own use and the needs of the community. They return a gift to the earth and tend to the well-being of the wiingashk. The braids are given as gifts, to honor, to say thank you, to heal and to strengthen.” In so doing, she notes, “the sweetgrass is kept in motion … passed from hand to hand, growing richer as it is honored in every exchange.”

I go back to my son’s question, and I like the essence of it, but as I read Kimmerer’s stories, I wonder if I couldn’t reframe it somehow, tying it in some way to to something more communal, something more expansive than the relationship of my mind and body and more connected to our relationship with the earth. For the moment, I’m trying to disentangle my limbs from the pigeon pose, reminding myself as I look forward to steeping a cup of cherry lemon green tea that a better relationship between my own mind and body will put me more at ease with the world.

Photo by Lucas Schlagenhauf, Creative Commons License via Flickr. Post by LW Willingham.

We’re reading Braiding Sweetgrass as a community and invite you to join us as we explore the riches of this book, tugging against the strands we’re braiding between us, together. If you don’t yet have the book, enjoy this reprint of the first chapter.

Buy Braiding Sweetgrass Now

- Earth Song Poem Featured on The Slowdown!—Birds in Home Depot - February 7, 2023

- The Rapping in the Attic—Happy Holidays Fun Video! - December 21, 2022

- Video: Earth Song: A Nature Poems Experience—Enchanting! - December 6, 2022

Maureen says

I enjoyed reading this, LW. I have all kinds of mental visuals of people in yoga positions. (There is an excellent documentary on the subject of yoga on Netflix.)

My adventurous son has a friend who is a Native American. They often go on retreats, and various ceremonies are enacted. D’s been a firekeeper a number of times. When he was traveling in South America, he spent time in the Amazon with a shaman, learning about plants, and learned a few words from Mayans he met as well.

I have this title on my reading list. I have quite a few books I’m juggling right now, so I don’t think I can get to this book now, though I do look forward to reading it.

Will Willingham says

Maureen, I’ve mostly been listening to the audio book with this one, which is read by the author. Her voice is a delightful match for the book. Fascinating, about your son. 🙂

Sandra Heska King says

Miigwech, LW. I’m loving this book so much. A big part of that, of course, is because my grand girl Lil is part Odawa (Ottawa), and we’ve been to pow-wows when she dances. (I’ve also learned some basic words.)

It’s taking me some time to read, though, because I need to linger over lines. I’ve read before about the children having their culture schooled out of them. 🙁

I loved the gift of the first cup of coffee spilled out on the earth and spoken words of thanks as the day began. It was a “second-hand” and “solitary” ceremony, but still Kimmerer said she could almost here the land murmuring, “Ohh, here are the ones who know how to say thank you.”

Her father couldn’t remember how the ritual got started. He thought at first it was to clear the spout of the plug of grounds. “But, you know,” he said, “there weren’t always grounds to clear. It started out that way, but it became something else. A thought. It was kind of respect, a kind of thanks. On a beautiful summer morning, I suppose you could call it joy.”

That, wrote Kimmerer, is the “power of ceremony: it marries the mundane to the sacred.”

This morning when I walked the dog at the park, we bypassed the benches and the picnic tables and just sat for a bit on the grass looking out over the lake. (I scouted for fireants first.) There was something sacred about planting my body directly on the earth.

Will Willingham says

I love the way you’ve been able to share in Lillee’s experience over the years. I loved that about pouring out the coffee and that there was a question about the origin, but that even so, the small ceremony of it had great value in reminding of the relationship with the earth.

Laura Brown says

I’ll start where you ended, thinking about rituals that better acquaint mind and body, and how they might also be stretched to build or strengthen relationships with others. What is my sweetgrass and how can I keep it moving? I don’t know. But I want to find an answer.

Possibly my favorite sentence: “I mumble namaste to myself.”

Will Willingham says

This is a good question, what is my sweetgrass. 🙂

Lauree says

this is long after this posting. i suppose it says something about things coming when your heart needs it. i cried my way through braiding sweetgrass (on audio) in the spring. to me it seems ritual as a moment of peace is more important now than ever.