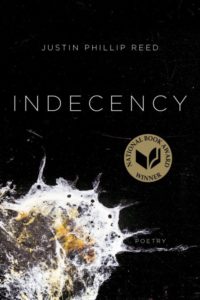

The 2018 National Book Award for Poetry was given to Indecency by Justin Phillip Reed. Reed is a young poet living in St. Louis. Indecency is his first published collection; he published a chapbook, A History of Flamboyance, in 2016.

I saw the National Book Award announcement, but I didn’t realize the St. Louis connection. A couple of days after the announcement, the “good news” columnist for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch had a brief item about Reed living in St. Louis. Later, the book editor included a short note and the Associated Press story about the winners on her book blog.

A St. Louis poet, with strong connections to Washington University in St. Louis, including an M.F.A. degree and a junior writer position wins the National Book Award for Poetry, and that’s how the local paper covers it? Go figure. At least Washington University issued two new releases, one from the university and one from its College of Arts & Sciences. This past May, St. Louis Magazine did an interview with Reed specifically about his new collection, and it’s filled with interesting ideas and discussion. (Read the interview; he explains where the title of the collection came from.)

Indecency is not an easy collection to read. I suspect it was not an easy collection to write. It’s filled with raw scenes and language. It’s about race. It’s about a black man, gay. It’s about the violence inflicted on black people. It’s about relationships. How Reed uses language in these poems reflects the violence of experience. It’s as if he’s walked up to you and grabbed you by the lapels of your coat, demanding that you look. Don’t just turn your face away, pretend to look somewhere else, or drive your car quickly by. Stop, he says, and look. See what’s here.

Black Can Sleep

quick as catch can. Corner

hanger-on, black as a dead

cell waiting to low-ceiling its empty

belly down on a mop-dragged floor.

Lure of draining, black goes

to ground. Rain dangle: black hitches

like hick cargo. Call round. There it is

a thumb in the milk, trunk junk

strewn across a killing

of lilies. Oh Lord,

black the valley. Wise me

slather mirth, lip the gum. The news

their black tomb of tooth sucks out

won’t news. Black know: Pops

a stone stopped quiet

(of all sounds) in the rolling.

Black cancer. Black sugar.

Black pressure. Black taken

off life support’s hollow leg. Use

to be an hour visited

on us, stained Colt & wild

around the neck, ex

of auntie, blackest one yet,

picked up only after zip,

pockets just a snatch of ay

young black, how you live?

The 38 poems in the collection are jarring, always. They’re also disturbing and demanding. For someone like me, who’s lived in St. Louis for 40 years in two of its more prosperous suburbs, to read St. Louis poems like “Gateway” and “About a White City” is to see another city you barely acknowledge but that you know exists. It’s the city I spent nearly a year roaming around and through when I was the communications director for St. Louis Public Schools. But I roamed, helicoptering from one school and community meeting to another. I didn’t live there. I went home at night to my quiet, safe suburb, which after a time seemed almost as unreal as where I was working eight to ten hours a day.

Justin Phillip Reed

The poems of Indecency were born on those streets. They’re as haunting as the streets they come from.

Born and raised in South Carolina, Reed was expelled from high school three times and dropped out of college once. He eventually earned a B.A. degree in creative writing from Tusculum College and, as mentioned, his M.F.A. in poetry from Washington University. He received fellowships from the Cave Canem Foundation, the Conversation Literary Festival, and the Regional Arts Commission of St. Louis. His work has been published in several literary journals.

To read a collection like Indecency is to disabuse yourself of those notions you hold as “part of the background.” These are hard words, expressed in long and short poems, about a young man’s life and experience.

Related:

Justin Phillip Reed accepts the National Book Award for Poetry.

Photo by Lariliikala, Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post by Glynn Young, author of the novels Dancing Priest, A Light Shining, Dancing King, and the newly published Dancing Prophet, and Poetry at Work.

__________________________

“I require all our incoming poetry students—in the MFA I direct—to buy and read this book.”

—Jeanetta Calhoun Mish

- Longfellow’s “Paul Revere’s Ride”: Creating a National Legend - April 17, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Katie Kalisz and “Flu Season” - April 15, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Michelle Ortega and “When You Ask Me, Why Paris?” - April 10, 2025

Van Prince says

*Historic Facts*

Have blacks of today

read America’s History

how the offspring of the slave master

are benefiting from slavery today

yet the descendants of slaves are not-

Have blacks of today

read America’s of History

how black leaders of Africa conspired

with American white leaders

to sell our forefathers into slavery

allowing the Institution of Slavery

of blacks in America to last for four centuries-

Have blacks of today

read American History

on blacks being freed from slavery

without more, no support at all

having to endure Reconstruction,

Jim Crow Segregation, and Affirmative Action-

Have blacks of today

read American Historey

that Africa nor America

haven’t made Reparation for Slavery-

By: Van Prince