Editor’s Note: Some of the best work Tweetspeak has to offer is regularly set aside as thanks to our Patrons, whose generosity helps us bring kindness, friendship, and joy to the world.

Today, we hope you’ll enjoy this touching piece as our holiday gift to you—a piece that ordinarily would have been for patrons only.

***

When Anatoly Nayman recounts his first meeting with Anna Akhmatova, he describes her gesture of hospitality.

The woman who had let me into the flat brought in a saucer on which lay a lonely boiled carrot, which had been peeled perfunctorily and had already dried up somewhat. Perhaps such was her diet, perhaps it was simply Akhmatova’s wish, or the result of disregard for housekeeping, but for me at that moment this carrot expressed her infinite indifference–to food and everyday routine, which was almost asceticism, especially viewed alongside her unkemptness and her poverty.

Akhmatova was born Anna Andreevna Gorenko to an upper-class family in 1889 in Odessa on the Black Sea coast. Her parents soon moved to St. Petersburg, and she spent much of her early life at Tsarskoye Selo, the imperial summer residence. She began to write poetry when she was eleven years old. Her father was afraid her poetry would bring shame to the family name, so she assumed the surname of her maternal great-grandmother. She did, however, retain her patronymic (middle) name based on her father’s name of Andrei. (Russians often address each other using first and patronymic names, especially colleague to colleague or student to professor.)

During her lifetime Akhmatova saw famine and wars and repression and resistance and revolution. There were false charges and secret surveillance and purges and imprisonments and executions. Millions of people died. There was literary censorship.

Her first husband was executed. Her second husband died from tuberculosis. Her third husband died in prison. Her son was imprisoned several times. Out of the four great poets of her time (including herself), Mandelstam died in a work camp, Tsvetaeva died by suicide, and Pasternak was forced to refuse the Nobel Prize. Akhmatova herself contracted typhus and tuberculosis. She lost touch with her family. She was labeled “half harlot, half nun,” probably with many connotations. The secret police kept her under constant surveillance.

The majority of her life was lived out amid loss and grief and in poverty. Nancy Anderson writes, “Like a nun she saw herself as having a vocation that required her either to live on the charity of others or go without.” She did earn some money from translation. For thirty years she had no home of her own and lived as a guest with others. When she was expelled from the writer’s union, she lost access to food ration cards. By the end of her life, though, the government finally awarded her a small pension and an even smaller cottage.

Akhmatova could have fled like some others but chose not to. She stayed to write the stories, to honor the dead, and to keep memories alive. James Joyce wrote in Ulysses, “You cannot leave your mother an orphan.” She later modified the line to “You cannot leave your Motherland an orphan.” There was much government opposition to her work and her apartment was secretly bugged, but she loved her country, and the Russian people loved her.

She and her friends helped each other—whether taking up collections for clothing or even memorizing each others’ words. Once, in August of 1920, Larisa Reisner, a former mistress of Akhmatova’s first husband, visited and found Akhmatova “emaciated and dressed in rags, boiling soup in a borrowed saucepan.” (p. 34) Reisner used her connections to get food, clothing, and medical care for Akhmatova’s second husband, Vladimir Shileyko, and arranged for Akhmatova to get a library job.

According to Joseph Brodsky in his introduction to Nayman’s Remembering Anna Akhmatova, “In her time, the smallest scrap of paper had the knack of becoming a piece of evidence. Therefore, she’d put her pen to paper only in the case of linguistic necessity, i.e., because of a poem.” But sometimes even necessity had to be nixed.

A small circle of longtime friends dared to risk continued association with her. During the many years that Akhmatova was silenced, she relied on these friends to memorize her poetry. One of those was Lydia Chukovskaya—poet, editor, publicist, and memorist. Chukovskaya recalled,

Suddenly in mid-conversation, she would fall silent, and signaling me with her eyes at the ceiling and walls, she would get a scrap of paper and a pencil; then she would loudly say something very mundane, ‘Would you like some tea?’ [… ] then she would cover the scrap in hurried handwriting and pass it to me. I would read the poems, and having memorized them, would hand them back to her in silence. ‘How early the autumn came this year,’ Anna Andreevna would say loudly [to foil anyone listening in] and, striking a match would burn the paper over an ashtray.” (p 62-63)

Akhmatova’s friends helped keep her work alive. Through a kind of whisper network, they preserved one another’s lines and stanzas before they burned the original copies. Requiem, one of Akhmatova’s most famous pieces, maybe the most important, was “written” this way. She composed it over several years, but could not speak it or leave any trace of its words. It was a dangerous work, especially since it explicitly named Nikolay Yezhov, chief of the secret police during Stalin’s Great Terror. It opens with a prose introduction describing Akhmatova’s personal experience standing in line every day for seventeen months waiting for news of her son.

Instead of a Preface

In the terrible years of the Yezhov terror, I spent

seventeen months in the prison lines of Leningrad.

Once, someone “recognized” me. Then a woman with

bluish lips standing behind me, who, of course, had

never heard me called by name before, woke up from

the stupor to which everyone had succumbed and

whispered in my ear (everyone spoke in whispers there):

“Can you describe this?”

And I answered: “Yes, I can.”

Then something that looked like a smile passed over

what had once been her face.

(translated by Judith Hemschemeyer)

Several “cycles” or shorter poems follow that describe not just her personal grief but the communal grief of all the women standing in the line.

To ensure the survival of Requiem, she taught it to her closest female friends who would remember the poem after her death—especially in the event she might be arrested and killed. When she made changes to her poem, she asked her friends to remember them, insisting that the final draft of the poem be the one they would remember from now on. Martin Puchner writes, “Their minds became the paper on which Akhamatova preserved and revised her poem word by word, comma by comma, with the precision typical of literature crafted with an eye towards the permanence of writing.”

Anna Akhmatova died of congestive heart failure on March 5, 1966, just shy of 77 years of age. This was 13 years to the day after Stalin’s death on March 5, 1953.

On large count because of friends who cared for her, Akhmatova lived a longer-than-expected life before her broken heart gave out. And because they stored her words in their minds, her poetry lives on like a bottomless bowl of tender glazed carrots with 800-plus poems and fragments. She is remembered as one of the greatest of all Russian poets—indeed, one of the great poets of the world.

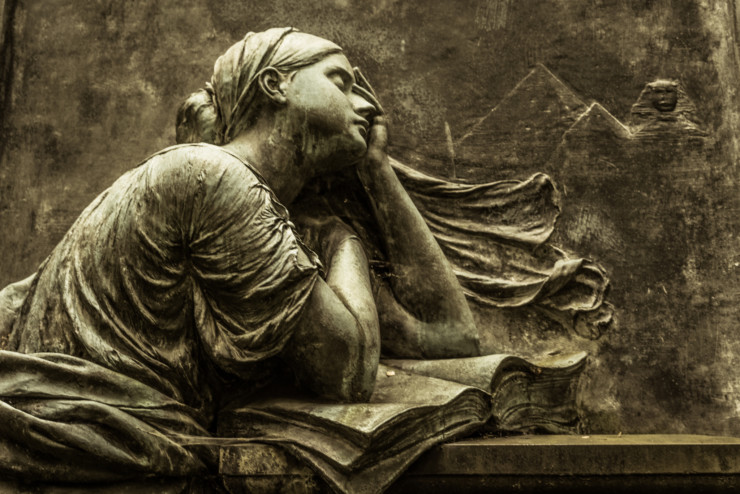

Photo by xk1lima, Creative Commons license via Flickr. Post by Sandra Heska King.

The participants in this podcast begin to talk about “Requiem” at about 17:49, but the entire discussion is worthwhile, including what follows the podcast.

Discuss With Friends (Or Use in Personal Journaling)

1. Look at the sculpture at the top of this post. Take special note of the right side of both the woman’s clothing and the pages of the book. How do these parts of the sculpture potentially alter any first impressions you may have had of the art?

2. What role can visual or literary art play in an oppressive situation? Consider, for instance, Akhmatova’s “Instead of a Preface” (reprinted above), that includes the woman’s question, “Can you describe this?”

3. Are there dynamics in your own life or the life of your community (online or on-the-ground) that threaten to oppress your spirit, or the human spirit in general? What are these dynamics? Do any of them mirror, if even in a small way, the oppression that Akhmatova suffered? How can her story inspire you to preserve your own spirit or the human spirit?

4. Martin Puchner writes, “Their minds became the paper on which Akhamatova preserved and revised her poem word by word…” Do you have friends for whom you play the role of “paper” that preserves their spirit, their art—or something else they care about? Do you have friends who play this role for you? What are the means by which this happens? If the idea is of interest to you, how can you facilitate it more?

5. Akhmatova chose to stay in a country she could have left—chose to be a voice where, literally, she could not freely speak. Consider writing a poem from the perspective of her country or her countrymen, that explores this choice.

when you become part of the Tweetspeak community

that helps us continue to bring

kindness, friendship and joy to the world.

Just click on the gift, then join us through Patreon

for as little as $5 a month, to get started.

- 50 States of Generosity: Iowa - April 7, 2025

- 50 States of Generosity: Montana - January 27, 2025

- 50 States of Generosity: Idaho - December 16, 2024

Glynn says

Akhmatova’s “Requiem” did for Stalin’s regime what Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn did in fiction. She wrote it over 36 years. It was published in the West in 1963, but it wasn’t until 1987 that it was published in what was then the Soviet Union. Sometimes we write for posterity alone.

I can’t even begin to imagine the pain and suffering she experienced.

Sandra Heska King says

Thanks for adding that important bit of information on the poem’s publishing, Glynn. And for reminding us that “sometimes we write for posterity alone.” That’s a sobering–and encouraging–thought.

L.L. Barkat says

From a publishing standpoint, it surely ended up being for posterity (not easy for most writers, I suspect).

But I do think that she wrote for life as well—her life, her friends’ lives, even the life of the woman-stranger who asked, “Can you describe this?” In this way, Akhmatova was a voice, a spirit, in a silent and spirit-destroying place.

Sometimes we write for the moment, not for posterity. And this, too, has profound implications.

I am thinking that this relates to an earlier Friendship Project post, where I suggested that writing becomes “almost a kind of place.” I believe that Akhmatova’s writing was a meeting place, in a landscape where people could no longer openly meet. I believe it was a dwelling place, with a wide open door for those who needed to come in and find solace and hope. It was the kind of place that no police could evict her and her community from.

Sandra, you (and now Megan) are teaching us how to live inside writing together—as, together, we memorize poems from the past, or the present, with wide open doors for those who will take the time to re-construct them in their minds, and come in.

Thank you for this beautiful, if hard, piece, about a fellow writer from the past.

Sandra Heska King says

As always, I love your thoughts, Laura. Our writing can be a place of invitation, community, hospitality, hope, and life. And that’s whether it’s a single boiled carrot on a given day or maybe a deep dish of tender buttered and glazed ones. It can be a gift–and even a responsibility, whether those words are meant to breathe life into a given dark moment or remain for the future. Of course, it’d be nice to think our words could hold a timeless place, but maybe that’s really out of our control.

I was also deeply impressed with Akhmatova’s courage (and that of her friends) in the face of great personal stress and physical danger. I won’t forget her.

Matthew Kreider says

This is wonderful, Sandra. I love how you show us the boiled carrot and the community. Poetry is a gathering of gifts—and those two elements show us exactly that.

This makes me think of one of my adult students…she is unemployed, receiving social assistance, and going long stretches of days without spending even a dime…

Yesterday, when I was helping with her resume and cover letter, I noticed she had a folder—named Poems—on her Google Drive. Of course this led to me asking questions—yes she writes poems—and of course I told her that I would love to see one, if she felt comfortable sharing…

She emailed me one of her “intense” poems, and in that moment I felt the beauty inside important things. Like the beauty inside a boiled carrot, inside a community—inside poetry.

Thank you for sharing your words at Tweetspeak…

Donna says

“I felt the beauty inside important things.” Love the way you said that. I bet it meant a lot to her to be able to share her poem.

Sandra Heska King says

I love this, Matthew. And the gift you gave her of asking, and the gift she gave you of sharing. There is beauty in this story. Thanks for sharing it–and the gift of your comment.

Donna says

What she did with her life… oh.

I’m at a loss for words. She was a hero, I think.

Thank you for this, Sandra. It’s beautiful.

Sandra Heska King says

Thank you, Donna. A hero, yes. Her courage and perseverance blow me away.

Megan Willome says

Sandra, this is exquisite. It makes me want to know more of Akhmatova’s work.

Sandra Heska King says

Thank you, Megan. And yes… I’m still reading her words and words about her.

Megan Willome says

Finally wrote from your prompts. Here’s my take on no. 5:

I stand in the gap

of this house divided. This

house that shall not fail.

Sandra Heska King says

Shades of Lincoln. 🙂

I love that these are words you found and that you came back to share them. She was definitely a gap-stander, I think, for the land and people she loved.

Laurie Klein says

Sandy, this is deeply, beautifully wrenching: to read of her life, her losses, her clandestine means of getting the work out. Moving, too, to view her portrait and hear voice given to Requiem.

You’ve made carrots unforgettable.

A quick google (National Eye Institute) alerts me there is truth “under certain conditions” to common lore about beta carotene improving one’s vision. Across the decades, far-seeing Akhmatova stirs and sharpens my admiration, compassion, and aspiration.

I just read this admonition to writers, from Matthew Burnside (over at Brevity): “In short, strive to be that which helps all beside you float onward through the storm.”

Anna did so. As have you.

Sandra Heska King says

Oh, Laurie. Thank you so much. And I love how you’ve seen deeper into that little carrot.

A funny story… my brother used to take a carrot–unwashed and unpeeled, straight from the fridge, to bed with him like some kids take a bottle. (Well, bottles in bed aren’t cool any more.) He ate so many carrots, his skin turned orange.

Michelle Ortega says

Beautiful work, Sandy! I envision the urgency and intensity with which her friends memorized those precious lines. Y

Sandra Heska King says

Thanks, Michelle! Thank goodness for brave friends.

Katie says

Sandy,

I’m perplexed by the pyramids and sphinx in the background.

Do you know the name of this sculpture?

Sandra Heska King says

Katie, I’m so glad you asked! I never (well, I might have a couple of times) follow the photo credit link on these posts. The photo editor searches for them, I think. But I followed the link–and found that it’s called “Girl and Grief.” How perfect is that?

Katie Brewster says

Perfect indeed!

Bethany R. says

I was curious about that too. 🙂

Sandra Heska King says

🙂

Bethany R. says

Haunting and beautiful. This article will stick with me.

Sandra Heska King says

Thanks, Bethany. I still can’t get her out of my head.

Ann Kroeker says

I’m struck by the commitment of those friends, holding her words inside them, smuggling them out of her apartment in their minds and hearts until the poems could find a home.

Sandra Heska King says

Yes. Such courage. I’m not sure I’d be as daring. Thanks for stopping in, Ann. 🙂

sydney mann says

wonder. who read the poem akhmatova requiem so beautifully?

Sandra Heska King says

It *is* a beautiful reading. If you click over to You Tube, it doesn’t credit a specific person, just “A Poetry Channel”