Recently, I spoke to a group of fourth graders about how I go about writing creative nonfiction, and one tip I gave them was that writing a true story is not just about retelling the facts. Unless you’re an elementary school principal listening to who pushed who first on the playground, very few people are interested in a blow-by-blow account of our days. (I’d argue that principals don’t care too much, either.)

“So what you have to do,” I told them, as I sat next to an easel like the one I used to have in my classroom, “is choose something to write about that is true, but also bothers you a little bit.”

I went on to tell them that if they are bothered by the truth, then that is a sign they’ll need to figure it out. “And that means,” I said, as I leaned forward to the circle of kids sitting around me, “that you’ve found yourself a story.”

To sit with what bothers us in order to transform it into a story or poem is not an easy task. It can be downright overwhelming. One response I have for this concern is to suggest reading Marilyn McEntyre’s Make a List: How A Simple Practice Can Change Our Lives and Open Our Hearts.

I’ve read her book and am making my way through the many invitations she offers for list-making, but I also had the pleasure of hearing her speak about list-making at the Festival of Faith and Writing at Calvin College.

She describes lists as a mirror, “Something comes back to you,” she said. Making lists allows us to “drop into deeper places” and — my favorite — “move toward greater subtlety.”

Memories are tricky. I often sit down to write thinking I’ll tell the story of one moment, but in the process, I’ll remember something else. This happens throughout my day too. Such was the case the day I talked with fourth-graders. My plan was to discuss my writing process, but when I walked into the classroom and saw that easel, it was almost as though I was assaulted with nostalgia. It was difficult to concentrate on what it was I planned on saying, and I’m afraid I didn’t say much worthwhile.

McEntyre explained that list-making allows us to name something and “naming helps [us] contend.” My husband, Jesse, and I have been discussing teaching for several months now, and he says that until I can figure what bothers me and turn that into a story I will not be able to figure out how I feel and what I think. I cannot contend.

There seems to be too much to contend with for me when it comes to teaching, but seeing the easel felt familiar and good, like a wave from an old friend and an offer to sit and wonder.

I think I can contend with an easel.

Try It

For this week’s prompt, think of a memory, a moment, or an experience that bothers you. It should feel as though it’s too big to tell, too scary, too sad, even too hilarious. Next, make a list that includes objects, people, or sentences or phrases related to the memory. Finally, see if you can craft a poem using part of the list.

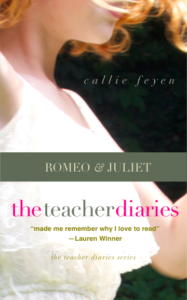

Photo by Noriaki Tanaka Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post by Callie Feyen, author of The Teacher Diaries: Romeo and Juliet.

—JJN Mama, Amazon reviewer

- Poetry Prompt: Courage to Follow - July 24, 2023

- Poetry Prompt: Being a Pilgrim and a Martha Stewart Homemaker - July 10, 2023

- Poetry Prompt: Monarch Butterfly’s Wildflower - June 19, 2023

Sharon A Gibbs says

Callie, I love your writing and see how you teach through it. 😉 This perfectly-timed piece asks me to give attention to my own easel(s). (They seem to pop up in corners when I least expect them.)

A small group of women writers I “guide” have voiced concerns over writing about those things that bother them. Maybe we can look at our easels together. 🙂

Thank you,

Sharon

Callie Feyen says

Thank you, Sharon. I appreciate your comment.

I would love to read a set of “easel” poems, or scenes, or essays. I know it’s hard to write about what bothers us, but I do think that’s the time we have a great story on our hands.

Richard Maxson says

The small Christmas cardigan

lost, the reindeer unraveled,

set free in the snow.

The Milky Way floats

like distant flakes

lost in their drifting.

There is a day, a smile,

in the time that snow

fell in the flash of warm light.

I always find you there.

Callie Feyen says

I feel chilly reading, “small Christmas cardigan,” and, “reindeer unraveled,” even before I read the word “snow.” I wonder if it is the common consonants in each phrase, or if it is the feelings that the images produce.

Then I feel as though I am falling, like the flakes, and the poem seems to move fast.

The last line takes my breath away, and I imagine both a snowflake settling, and on the verge of being swept away. I think that’s why I caught my breath.

Dave Malone says

I second Callie’s observation of the well-chosen words. And I absolutely love that first stanza. What a crisp image—that the sweater unravels, and the reindeer is let loosed. And to where? To the outdoors, of course. To snow. To that mystery. Bravo.

Will Willingham says

“A true story is not just about retelling the facts.”

And this is why, for me, so much fiction rings truer than nonfiction.

Callie Feyen says

Agreed. This is also why I read fiction more than nonfiction, and I ask myself, “How can I do that when I write CNF?” Story, must always come first. Dress the truth up in story. I think that’s the only way to tell it.

Katie says

She walked the shoulder

confusion shown on her face

why did we not stop

why were we afraid

when she looked anxiously up,

down the road to where

she saw us come, go

blowing past, hurrying on

not stopping to see

if possibly there

might be ways for us to help

to show compassion

hearing, listening

asking her, what do you need

what can we do, now?