Except for the five years I lived in Texas, I’ve never lived more than 15 miles from the Mississippi River. In known and unknown ways, the river has shaped my life.

My earliest memory of the Mississippi was, oddly enough, a manmade extension of the river. It’s called the Industrial Canal, in the Lower Ninth Ward of New Orleans. My mother was raised in the Lower Ninth, and when I was a child two of her sisters lived there, one of them about 50 feet from the levee. Nothing was more natural (and occasionally terrifying) than to run up the levee and see the ships moving to and from the river. It was terrifying because my cousins and I were always warned by my uncles about the dreaded nutria that inhabited the levee. We never saw one, but we always believed the stories. Why would our uncles lie to us?

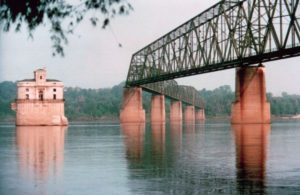

One of the steamboat houses on New Orleans’ Industrial Canal (information via Wikimedia)

We’d walk the top of the levee toward the Mississippi. It wasn’t far, perhaps 500 yards. And we’d pass what were known then and now as the “Steamboat Houses,” built by ship captains for their families. Colorfully painted and decorated with architectural gingerbread, they were set back from the levee, with the main living quarters on the second floor (a hedge against a levee break or flooding during a hurricane).

Years later, while in college at LSU in Baton Rouge in 1973, I went with friends to stand at the top of the levee and look a few feet down at the river. It was the Great Flood of 1973, and none of us had ever seen the river that high. Twenty years later, I was in St. Louis during another natural disaster — the Great Flood of 1993. St. Louis is an island, surrounded by the Mississippi, Missouri and Meramec rivers. All three flooded in 1993.

It was bicycling that reacquainted me with the river. I followed trails and marked streets that eventually led me to the Mississippi River overlook at a small park in south St. Louis. The view was (and is) majestic –— you can look east a good mile or two to the Illinois bluffs, south to what’s called the Jefferson Barracks Bridge (Interstate 270/255), and north to the bridges reaching across the river into downtown St. Louis. I’ve composed more than one poem standing and sitting in this spot.

The Chain of Rocks Bridge in St. Louis (Wikimedia)

And then I could bike north, finding my way to the Arch and the River North Trail. The trail follows the river for about 12 miles, and that’s 12 miles of old mostly abandoned, industrial St. Louis on one side and the treelined river on the other. The trail ends at the Chain of Rocks Bridge, which opened in 1929 and closed to vehicular traffic in 1970. Today it’s used only by pedestrians and cyclists. The view from the bridge to the south is inspiring — you can see all the way to the skyscrapers of downtown St. Louis.

And, yes, I made sure I biked all the way to the Illinois side.

This great river, this Mississippi River, drains 32 states and two Canadian provinces.

One author “owns” the river, and that’s Mark Twain. He was raised in the Mississippi River town of Hannibal, Missouri. In his 20s, he learned to pilot a steamboat. His longish short story, Old Times on the Mississippi, was published in 1876, and his collection of articles and essays, Life on the Mississippi, was published in 1883. Today, you can visit the castle-like, brownstone, Tudorish Mark Twain House in Hartford, Connecticut, which also offers a museum experience.

It was The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1884) that established Twain’s clear literary title to the river. He had begun writing the novel several years before but had run into a major writer’s block that he couldn’t get around. Why would a runaway slave (Jim) head south into the heart of slave-owning territory? Twain couldn’t answer that one. Eventually, he solved it in typical Twain fashion: He ignored the problem and finished the story anyway.

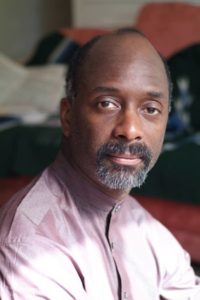

Eddy Harris

Some 30 years ago, a St. Louis writer named Eddy Harris decided to canoe the river from its source (Lake Itasca in Minnesota) to New Orleans. He started in late October of 1985 and finished not long after Thanksgiving. He recorded his journey in Mississippi Solo: A Memoir, which veteran travel writer Paul Theroux called “an original contribution to the literature of travel.”

Harris was not exactly an experienced canoeist; he had to borrow a canoe. He had had some experience in camping, and virtually every night of his trip found him camped out somewhere along the river. Friends thought he was crazy.

Harris is also a black man who, as he writes, doesn’t think of himself as a black man first. His race plays a role in the story — he’s conscious of the fact that he sees only one black man in Minnesota, fishing along the riverbank in Minneapolis — but Mississippi Solo is more a story of setting a goal, a big goal, and accomplishing it. He meets with storms, discovers the dangers of barge and towboat traffic, finds less prejudice than he expected (but he does find some), and has an encounter one night with two men bent on mischief (at best). He chases them off by firing his pistol. He also finds people who unexpectedly go out of their way to help him.

The Chain of Rocks Bridge in New Orleans, where Harris ended his journey. Today, it’s a double span. (Photo by Dunncon13 via Wikimedia)

Along the way, he considers the topography, how the river moves, and how people have tried to control it. He describes the many times he has had to maneuver through the lock and dam system on the upper Mississippi. As he begins to understand the river’s personality and its moods, he talks to it, and is delighted to find it talks back to him. And while Harris doesn’t describe it this way, he finds the river’s poetry and its song, the poetry and song that have been such a large part of my life.

“But rivers don’t really die, do they?” he writes. “They don’t end. They become the ocean, and the ocean becomes rivers, in a great cycle. And so there is only one river. It flows endlessly, spreading out across the world, multiplying, becoming other rivers, separating, rejoining, always going and never ending, always one with the other rivers. There is strength in the unity of rivers.”

We dredge them and channel them, build up our levees and drain their bottomlands, we build our towns and cities next to them, we fish them and use them for our trade and commerce. But we never really control them.

Photo by Pai Shih, Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post by Glynn Young, author of Poetry at Work and four novels: Dancing Priest, A Light Shining, Dancing King, and the just-published Dancing Prophet.

__________________________

“I require all our incoming poetry students—in the MFA I direct—to buy and read this book.”

—Jeanetta Calhoun Mish

- Poets and Poems: Forrest Gander and “Mojave Ghost” - March 27, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Siân Killingsworth and “Hiraeth” - March 25, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Donna Hilbert and “Gravity” - March 20, 2025

Sandra Heska King says

I loved learning a little more of your story. And this quote from Harris: “There is strength in the unity of rivers.” And that we can’t control them. Good stuff. I’ve added the book to my “want list.”

Michele Morin says

I think this may be the first piece I’ve read from you that tells anything about your own story.

There’s lots of good stuff here!

Thank you!

Glynn says

Michelle – the Mississippi River is a personal thing. It was something always there when I was growing up in New Orleans; you could stand on the levee by the French Quarter and see how wide it gets as it nears its mouth. Even today, biking from where I live in suburban St. Louis to the river is something like going home.

Margy says

Thanks for the review. Eddy Harris’s book sound like a perfect one for me to read. I have only seen the Mississippi River once, but we have many rivers in British Columbia that people canoe for long distances. I read many books about those experiences. I just saw a clip on TV about the nutria. They do look big and foreboding. Good thing you didn’t meet up with one as a child. I reviewed a classic author as a part of my review, John Muir and his hike into the Sierra Nevada, a beginning of what is now the Pacific Crest Trail. – Margy

Glynn says

If I remember correctly, nutria aren’t native to North America but to South America. They came to North America and Europe via fur farmers.

Katie says

Glynn,

A post for much reflection.

Meaningful as always.

In the third picture, what is the structure to the left of the bridge?

Katie

Glynn says

There are several of these scattered along the river. It’s a water pumping station that ties into water supplies.

Katie says

Thanks.