I consider J.R.R. Tolkien (1892-1973) and Middle-earth (timeless), and I find myself eventually arriving at Homer.

I’ve been reading about Homer and his Iliad and Odyssey, and the archaeological work that’s been under way for several years on what’s believed to be the tomb of Odysseus, or someone like him. We’re still learning that stories we believe to be myths, in the contemporary sense of that word, may actually be grounded in historical fact. It doesn’t mean they’re completely or historically accurate, but it does mean that the oral tradition they come from may be more historical than we realized.

Homer’s works were considered mostly fiction until 1870, when the German archaeologist Heinrich Schliemann discovered the site that is now considered the battleground of the Trojan War. Troy turned out to be a real place.

My introduction to Tolkien came through the paperback editions of his works pirated by Ballantine and published in the United States in the late 1960s. I was a college sophomore when I read them. Five years later I reread them, this time in the authorized edition published by Houghton Mifflin. I’ve reread them twice since then, once right before the start of the Peter Jackson movies and once after. They’re still astonishing works. And we wouldn’t fully understand how astonishing without the work and research of Tolkien’s son Christopher over more than five decades.

Christopher Tolkien is now 94; The Fall of Gondolin, published in August, is the last of the Tolkien tales. Christopher became Tolkien’s literary executor in 1973, with the death of his father. But his direct involvement had begun some 30 years before that, when he would occasionally attend meetings of The Inklings as they read from and discussed their works in progress. Christopher also accompanied his father to the funeral of C.S. Lewis in 1965.

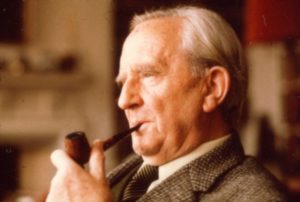

J.R.R. Tolkien

Without Christopher’s scholarship, research, and painstaking editing, we would not know that his father’s best-known works were actually only a relatively small (yet important) part of a grand, invented mythology, complete with chronological ages, geographies, peoples, and languages. While the writings were often incomplete, we can see the creative shape of what Tolkien envisioned.

It is a world of good and evil, where evil often triumphs. It’s a world where small numbers of small people (like hobbits) play outsized roles and accomplish heroic things. It’s a world of elves, dwarves, men, orcs, balrogs, wizards, and the living trees called Ents. It’s a world where men are often tempted and fall, and then pick themselves up again and fight on.

Where did this incredible world come from? The events and conditions that influenced Tolkien are well documented.

He and his younger brother were orphaned early. Following their mother’s wishes, they were raised by a priest in the Roman Catholic faith. Friends, and bands of friends, were always important, whether it was in school days, at university, in the war, or in the academic world. His love for the Edda and Norse mythology has already been noted. His academic expertise in Old and Middle English were important; he was a professor of Anglo-Saxon at Oxford’s Merton College (and “Middle-earth” is an Anglo-Saxon term).

Two influences are unmistakable.

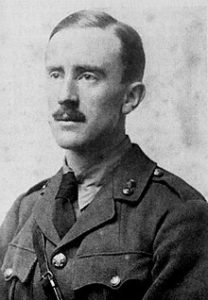

Tolkien in World War I

His early writing was shaped by the horrors of the Great War; he would spend his off-time at the front writing stories like The Fall of Gondolin. And the moonscape of the battlefields of France and Belgium certainly suggested the terrain for a place like Mordor. The war also taught him loss; of all of his close friends at Exeter College at Oxford, only one survived the war. (Two good resources on Tolkien and World War I are Joseph Loconte’s A Hobbit, A Wardrobe, and a Great War and John Garth’s Tolkien and the Great War: The Threshold of Middle-earth.)

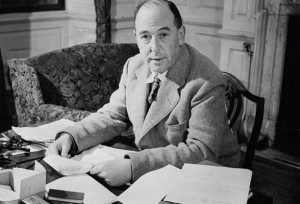

The second influence was C.S. Lewis. Lewis became one of Tolkien’s closest friends at Oxford. They were the heart of the Inklings. Tolkien played a critical role in Lewis’s accepting the Christian faith, and Lewis played a critical role in encouraging Tolkien, over an extended period, to keep at the writing and publish The Hobbit. Without Lewis, there might not have been The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings that eventually followed.

C.S. Lewis

Tolkien, thanks to his own writing and the tireless work of his son, has left us a legacy of abounding creativity and imagination. He’s left us with terrifying villains like Sauron and everyday, common-man heroes like Sam Gamgee, Frodo Baggins, and their friends Merry and Pippin. He gave us Gollum and Aragorn and Elrond of Rivendell. He showed us betrayal and he showed us selfless sacrifice. And he told us how myths can be made.

Best of all, he gave us the sheer enjoyment of enthralling stories. Middle-earth may or may not have the staying power of Homer. But its stories are worthy of the great battle of Troy and the great wandering that followed.

Related:

The Last of the Tolkien Tales: “The Fall of Gondolin”

A New Exhibition: Tolkien and the Making of Middle-earth

“The Fall of Arthur” by J.R.R. Tolkien

Tales of the First Age: “Beren and Luthien” by J.R.R. Tolkien

“The Children of Hurin” and “The Lay of Aotrou and Itroun” by J.R.R. Tolkien

Poets and Poems: J.R.R. Tolkien and “Beowulf”

Poetry Date: Sisters Read Tolkien and One Wears Dagger

Photo by Pacheco, Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post by Glynn Young, author of the novels Dancing Priest, A Light Shining, and the newly published Dancing King, and Poetry at Work.

__________________________

“I require all our incoming poetry students—in the MFA I direct—to buy and read this book.”

—Jeanetta Calhoun Mish

- Poets and Poems: Christina Cook and “Roaming the Labyrinth” - April 22, 2025

- Longfellow’s “Paul Revere’s Ride”: Creating a National Legend - April 17, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Katie Kalisz and “Flu Season” - April 15, 2025

Megan Willome says

I love the idea that the old, old stories (like Homer’s) are drawn from oral traditions of historical events. It makes sense as to why these tales get told and retold and continue to resonate.

I have not read all the Middle Earth stories, but the ones I have read feel similar, like ancient history. I expect we will still be talking about them 100 years from now.

Sandra Heska King says

As you know, I’m re-reading Madeleine L’Engle’s Walking on Water. She writes, “If the artist reflects only his own culture, then his works will die with that culture. But if his works reflect the eternal and universal, they will revive.” Or survive. Homer and Tolkien and Lewis and Shakespeare and others wrote timeless stories. Yes? And how cool to know they are based in fact as well as fantasy.

I am always amazed (and a little jealous) at how much detail you remember and have absorbed from your school years. That’s why you are legendary.