The fictional friendship is that of Samwise Gamgee and Frodo Baggins in The Lord of the Rings trilogy by J.R.R. Tolkien (1892-1973). The great trilogy is about many things — change, war, relationships, treachery, courage in the face of insurmountable odds. But the heart of the three books is the friendship between Sam and Frodo. In fact, it can be argued that the quest to destroy the ring of power would have failed without the friendship of the two hobbits.

The literary roots of the friendship between Sam and Frodo can be found in three gatherings Tolkien participated in during his life, all three of which were affected profoundly by the Great War.

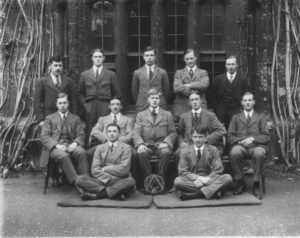

When Tolkien was a teen at King Edward’s School in Birmingham, he and several other friends formed the TCBS, or Tea Club and Barrovian Society, devoted to promoting beauty, literary discussions, and having fun, including jokes and pranks. “Barrovian Society” was a reference to their having tea at Barrow’s Department Store. The TCBS remained in close touch well into 1915, when virtually all of them were involved in fighting World War I. Only two TCBS members, Tolkien and his friend Christopher Wiseman, would survive the war.

The Apolausticks

At Exeter College in Oxford, Tolkien formed the “Apolausticks,” mostly a literary discussion group. According to John Garth in Tolkien at Exeter College, the group was primarily a literary society. Members read, discussed, and debated well-known authors. Colin Cullis was Tolkien’s closest friend in the club. Both had visual and verbal talents, and shared favorite authors. Many of these would fall in World War I as well. (Garth’s Tolkien and the Great War: The Threshold of Middle-earth is one of the best sources on how the war affected Tolkien and his literary work.)

And then, as an academic at Oxford, Tolkien was part of the Inklings, which included C.S. Lewis, Owen Barfield, Charles Williams, and others. This was indeed a creative writers’ group, meeting weekly for years to discuss their works in progress. The friendship between Tolkien and Lewis had already developed by the time the Inklings had begun to meet, and it was this friendship that was critical to The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings. It was Lewis who read early manuscripts of The Hobbit and kept encouraging Tolkien to keep at it, until it was finally published in 1937 and became a commercial success.

The Inklings

Tolkien and Lewis shared something else — both were veterans of the Great War. Both had been wounded and invalided for a time back in England. Both had lost close friends. Both had lost their mothers at a very young age. Tolkien played a significant role in Lewis’s embracing the Christian faith. Their friendship would experience great strains over the years, but it would endure.There are few accounts of funerals more moving than that of Tolkien and his son Christopher attending the funeral of C.S. Lewis in 1965.

It would be misleading to identify Lewis and Tolkien as the prototypes for Sam and Frodo. But the influence couldn’t help but be felt. The two men, very different in their personalities, had much in common, including a love for medieval literature. Tolkien wrote his great stories of Middle-earth, and Lewis was the faithful friend who encouraged him.

The friendship of Sam and Frodo survives great strains as well. And there are few accounts (or movie scenes) more moving than when Sam watches his seriously ailing friend sail off to the Misty Isles.

Photo by Andrew E. Larsen, Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post by Glynn Young, author of Poetry at Work and the novels Dancing Priest, A Light Shining, and the newly published Dancing King.

__________________________

“I require all our incoming poetry students—in the MFA I direct—to buy and read this book.”

—Jeanetta Calhoun Mish

- Great Friendship Tales: The Power of Sam and Frodo Starts With Tolkien - August 15, 2018

- The Kingdom Comes III - September 10, 2011

- The Kingdom Comes II - August 29, 2011

L.L. Barkat says

Very interesting history, Glynn. Sad, that just two men from that early literary group survived the war. Such realities surely must have given more energy to Tolkien’s sense of the lure and darkness of the ring.

In the video, that line that Frodo wouldn’t have gone far without Sam… I don’t know if that’s a line lifted from the books or not. But that’s how the greatest friendships feel: they take us places we wouldn’t have otherwise gone. Which makes me consider: if a friendship takes us nowhere, or if it seems to drag us backwards, maybe that says something we might want to pay attention to.

Megan Willome says

It’s one of the great literary friendships of all time, IMHO.

Katie says

Bilbo

Baggins, his name

Frodo, his son to claim

The ring, my precious, my

near end.

*****

Frodo, Bilbo’s son

Sam Gamgee his friend, his aid

One ring, lord and quest

Katie says

Revised my “almost” cinquain:

Bilbo

Baggins, his name

Frodo his son to claim

The ring, my precious, my near end

Gollum

Bethany R. says

Loved reading this, thank you.