We are sitting at the edge of Michigan’s own slice of the Caribbean—Torch Lake. The water is teal, sometimes turquoise. A handful of children are making little crayfish corrals of sand, circled and fortified by rocks, catching the creatures first with a net and pail. As for us, we’re fortified with turkey sandwiches and bottles of water and we’ve gathered ourselves on lawn chairs on the grass. My husband is reading John Grisham’s King of Torts and wonders aloud if the water is as cold here as it was in Lake Michigan the other day. I say it’s probably warmer, but not likely as warm as the Atlantic Ocean back home in Florida. I sprawl out in the sun and recite Romeo and Juliet to myself—completing Tweetspeak’s latest dare to commit poems to memory.

Two households, both alike in dignity,

In fair Verona, where we lay our scene,

From ancient grudge break to new mutiny,

Where civil blood makes civil hands unclean.

I’m thinking about the scene that lay in Thailand where a soccer team of twelve boys—the Wild Boars—and their coach have been stranded for two weeks by monsoon flooding. Households (different yet alike in dignity) from across the world have held their collective breath watching a dangerous international rescue effort that’s taken one life already. Before this day is over, the last four boys and their coach will be stretchered through that fearful passage to safety. If only we wouldn’t once again return to the other daily news that divides instead of mends.

Dennis sets his book down and ventures into the blue. I watch him catch his breath and tiptoe through the water. Considering crayfish and cold, I choose sweat and sunburn.

The next day we walk a narrow trail—the Shingle Hill Pathway (barely a path)—in the Pigeon River State Forest. Trees tower in silence while fern fronds reach to my shoulders. It’s a road seldom taken, the path veiled with dry pine needles and browned leaves. After an hour of trudging along with my head down to avoid brushing against poison ivy or tripping over tree roots, I’m restless. I hope for an elk to come crashing through the brush or a mama bear and her cubs to amble across our path. I’d even be happy to see a chipmunk or one of the many birds I hear. The most adventure we encounter is the man on the mountain bike who skids around a bend when he spots us. I return to Verona when Juliet learns that Romeo has killed her cousin Tybalt.

O serpent heart, hid with a flowering face!

Did ever dragon keep so fair a cave?

Beautiful tyrant! Fiend angelical!

Dove-feather’d raven! wolvish-ravening lamb!

Wow, was she ticked off.

My granddaughter recently posted a beautiful selfie on Instagram captioned, “I don’t wanna be a burden, so I wear a mask.” I told her it made me sad. “The words are from a song,” she said. I can’t find the song. Maybe there’s a song. Maybe there’s not.

I think about the masks in Romeo and Juliet. Romeo lamented of how fair ladies hide themselves behind masks. He wore one to hide his identity when he and his friend Mercutio crashed the Capulets’ costume party—where all the guests were “under cover.” Mercutio exclaimed, “Give me a case to put my visage in: A visor for a visor!” In other words, a tangible mask to cover the intangible mask—a mask for a mask. Juliet is broken up over what she perceives is Romeo’s “flowering face” masking his inner wickedness.

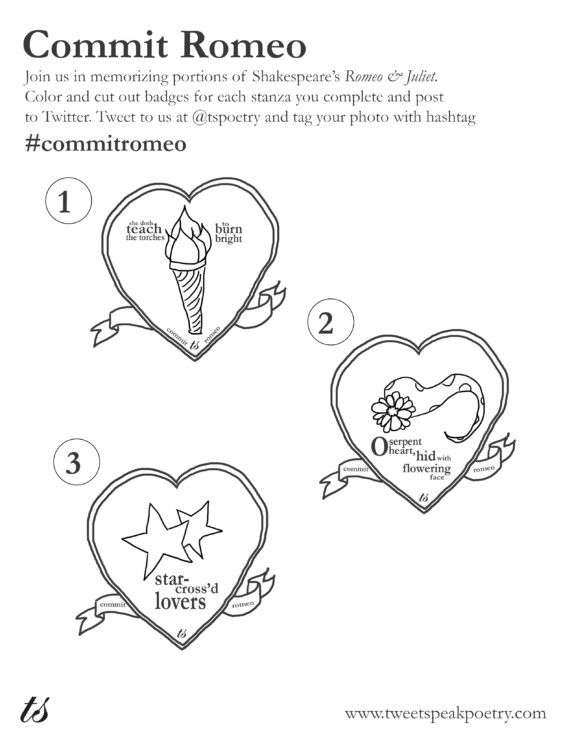

There’s this thing about committing poetry. My neurons fire up connections that may not seem to have anything to do with a poem I’ve memorized. Maybe it’s just a single word or a fern frond, and I go off the beaten path. The memorized lines keep me busy on mundane walks or on a long car ride, when I lie awake in bed or simmer in the sun. Today my brain’s sizzling over the divisions of two households, alike in dignity, and the crises that can pull people together if only for a brief season. In Romeo and Juliet, the death of two star-crossed lovers buried their parents’ strife, maintained over so many years they may have already lost sight of its beginning. Had they spent more time in the sun watching children collect crayfish, it might have been different.

Download Printable Commit Romeo Badges

Browse More Commit Poetry Dares

Photo by Jenny Downing, Creative Commons license via Flickr. Post by Sandra Heska King.

—Gregory Wolfe, Editor, Image

GET A FREE SAMPLE OF THE TEACHER DIARIES NOW

- 50 States of Generosity: Iowa - April 7, 2025

- 50 States of Generosity: Montana - January 27, 2025

- 50 States of Generosity: Idaho - December 16, 2024

Donna Falcone says

Impressive, my dear! I love listening to you recite poetry!

Sandra Heska King says

Thanks, Donna. What will be more impressive will be if I can recall it weeks later when I’ve topped it with other poems. 😉

Bethany says

I enjoy hearing how the poetry you mull over and memorize creates these unexpected connections, Sandra. 🙂

Sandra Heska King says

My connections are sometimes kind of random, but I’ve been reading about how one of the advantages of having children memorize poetry is that it stocks their mental shelves with ingredients to make all kinds of connections with more complex material as they get older.