My town of St. Louis claims Sara Teasdale as one of its own, but you wouldn’t know it from any sign, memorial, plaque or other designation. The city does not discriminate; T.S. Eliot is treated the same way, although he does have a plaque on the sidewalk in front of where his house once stood.

Teasdale was born in St. Louis in 1884. She lived in a house on Lindell Boulevard, today the northern boundary of Forest Park. In 1902, her family moved to Kingsbury Place, a few blocks north, on what in St. Louis was and is known as a “private street.” The city’s Central West End is filled with these private streets, built by developers for the wealthy. Homeowners on these streets today continue to be responsible for street repair, maintenance, and snow removal, and the homes and the streets have largely survived the vicissitudes of urban decay.

Sara Teasdale

I suspect Teasdale’s family moved because of what was happening on the other side of Lindell Boulevard—all of Forest Park was being converted into the 1904 World’s Fair. An interesting fact: Teasdale’s mother designed both of the family’s St. Louis homes.

She lived here when she was part of a local group of women artists called The Potters, which published its own literary magazine. It was here that she learned her first poem had been published in 1907 by Reedy’s Mirror, a local newspaper. Her first three poetry collections were published while she was a St. Louisan. She lived in the house on Kingsbury Place when she was courted by the poet Vachel Lindsay, who walked sadly away because he was not in the same economic and social class.

She married Ernst Filsinger, an admirer of her poetry, and they lived in St. Louis for a short time until they moved to New York City. It was there that, in 1917, she published Love Songs, which would win the Pulitzer Prize for poetry in 1918.

To read Love Songs today is to step backward in poetic time. During her lifetime, Teasdale’s poetry was broadly accepted by the public and critics alike. She didn’t fare as well with later critics, but her popularity can be seen by the 1918 edition of Love Songs I own—it’s the fifth edition. And while her love poems are filled with passion, it is a restrained passion, in keeping with her upbringing in an upper-class family. Edith Wharton was a generation older, but her writing of upper-class New York life is not unlike Teasdale’s poems.

A favorite poem in Love Songs is “Child, Child,” which is a poem for adults but sounds at first reading like one written by another poet connected to St. Louis, Eugene Field.

Child, Child

The voice and the eyes and the soul of a man;

Never fear though it break your heart –

Out of the wound new joy will start;

Only love proudly and gladly and well,

Though love be heaven or love be hell.

Child, child love while you may,

For life is short as a happy day;

Never fear the thing you feel –

Only by love is life made real;

Love, for the deadly sins are seven,

Only through love will you enter heaven.

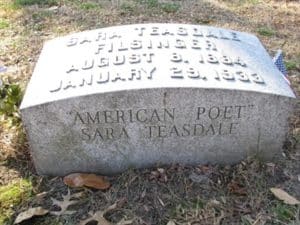

Teasdale’s grave in Bellefontaine Cemetery

The poem was probably written after her move to New York City, but to me, it bears the influence of St. Louis. I can see Vachel Lindsay walking dejectedly down the walk to the street, turning for a last look at the girl watching him from the window. I can see the girl with her young women artist friends, talking excitedly as they walk from Kingsbury Place to the grand spectacle that was the 1904 World’s Fair. I see the woman who, feeling the extreme loneliness of a husband who traveled extensively, later quietly filed for divorce, surprising him when he learned about it. And there’s the woman who reached out to Lindsay after her divorce, but he was married with children by then.

It’s the kind of poem that makes you consider whether it was predicting the future, when you read about Lindsay’s suicide in 1931 and Teasdale’s own suicide in 1933.

Teasdale is buried where all prominent deceased St. Louisans are, in Bellefontaine Cemetery in the northern part of the city. For Teasdale to be claimed as a St. Louis poet, that’s as it should be.

Photo by Omer Unlu, Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post by Glynn Young, author of the novels Dancing Priest, A Light Shining, and the newly published Dancing King, and Poetry at Work.

Browse more book reviews

Read Teasdale’s “There Will Come Soft Rains” and watch videos

__________________________

“I require all our incoming poetry students—in the MFA I direct—to buy and read this book.”

—Jeanetta Calhoun Mish

- Longfellow’s “Paul Revere’s Ride”: Creating a National Legend - April 17, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Katie Kalisz and “Flu Season” - April 15, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Michelle Ortega and “When You Ask Me, Why Paris?” - April 10, 2025

L.L. Barkat says

I loved this, Glynn.

Perhaps because of the wonder of many of the New York poems, it completely passed me by that Teasdale was not a native New Yorker.

It’s really interesting to see the quiet literary heritage of a place that’s tucked away in the center of the U.S. Teasdale, Eliot, Field. Who else? And, is there anything similar happening today in the midwest? (Maybe the Iowa Writers’ Workshop?)

Glynn says

The best known include Eliot, Teasdale, Field, Maya Angelou, Williams Burroughs, William Gass, Tennessee Williams, Kate Chopin, Jonathan Franzen, A.E. Hotchner, and Marianne Moore. Teasdale was a member of the Wednesday Club, a local writer’s club for women that included Irma Rombauer (The Joy of Cooking) and Edna Gelhorn, mother of Martha Gelhorn (one of Hemingway’s wives and a writer herself).

L.L. Barkat says

I’d love to hear more about the writer’s club—how it started, if it persists in some form today.

That is a fine list!

Megan Willome says

I love your “I see” paragraph. It helped me to see too.