I first read Kate DiCamillo’s story about Despereaux Tilling several years ago. But I should say that differently: A friend read The Tale of Despereaux to me.

Reader, do you know what it is to be read to? Not as a child, but as an adult? I might go so far as to say the world would be different—better, mind you—if the grownups kept reading books and stories to each other from time to time.

I suspect that DiCamillo believes something of the same, writing books that are immensely out-loud readable and in such a way that respects the sensibilities of readers along a broad spectrum of ages.

But that is not what we are here to talk about, is it. We’re here to talk about Despereaux. Despereaux and his family, Despereaux and the Princess Pea, Despereaux and the dungeon, Despereaux and Miggery Sow and Roscuro the rat. And soup. At some point we should talk about soup.

First, though, let’s talk about Miggery Sow for just a minute. I know, it’s out of order, but you’ll indulge me, yes? The introduction of Miggery Sow to the story came as something of an annoyance. I signed on to read—or have read to me—a story of a heroic mouse and a beautiful princess. All the wrongness that could possibly be born into a tiny mouse with too-big ears—he was sickly, he was born with eyes wide open, he didn’t wish to learn to scurry, he read books instead of nibbling the delicious pages, he talked to humans instead of hiding from them in fear for his life—improbably fell in love with a beautiful princess and even more improbably set off to save her when she was snatched away to the dungeon (the same dungeon he’d just narrowly escaped from), never to be seen again.

This was the story I wanted.

Instead, right in the middle, there was Miggery Sow with her desperately hard-luck story, with all of her wanting and no one’s really caring, with her improbable wish not to rescue Princess Pea, but to become her. Before long there I was, feeling unwished-for sorrow for Miggery Sow whose main job, it seemed to me, was taking up pages with her cauliflower ears.

I wanted the story of the mouse and the princess, and here I am talking about Miggery Sow. And don’t get me started on what the author does with outright evil characters like Roscuro, a rat so embittered by the loss of his chance to be in the light that he is determined to drag as many into the dark as he can. Let’s not talk about the way she makes us wish for him to be in the light. Reader, do you know what “empathy” means? I have a feeling you do. This is a thing that DiCamillo does—it’s part of the beautiful unruliness of her stories—making us feel something, even root for, her less savory characters.

Empathy or not, I wanted the princess story. I wanted Despereaux, the embodiment of disappointment, to rise fully above expectations, limitations, even his heart palpitations, and get the girl. In the end, he did and he didn’t. He set off to save the princess, armed only with a sewing needle and an entire spool of the red thread that had earlier marked his own sentence to live out his few remaining days in the dungeon. And he did it. He saved the princess, Mig, even Roscuro

And what of Despereaux? Did he live happily ever after? Well, he did not marry the princess, if that is what you mean by happily ever after. Even in a world as strange as this one, a mouse and a princess cannot marry.

But, reader, they can be friends.

The stories of Miggery and Roscuro end, if not perfectly neat and tidy, at least reasonably happily. Despereaux, it seems, settles for what he can get: the friend zone. Though perhaps he was not disappointed, even if I was.

This was the story that DiCamillo opted to tell. A story about darkness and light (and how close they live to one another), about love and loss, about identity and hope and soup. But maybe more than anything it was a story about stories, and how they too are light, are love, are identity and hope, even if they are not soup. When Despereaux is first banished to the dungeon (outed to the mouse council by his own family, no less, for being so disappointingly less than mouse-like) he encounters Gregory the jailer. Gregory has never before saved a mouse from the inevitable quick death in the dungeon. Despereaux asks why he would save him, then.

Because you, mouse, can tell Gregory a story. Stories are light. Light is precious in a world so dark. Begin at the beginning. Tell Gregory a story. Make some light.

The very last thing DiCamillo asks of her reader is to find some light in the story:

I would like it very much if you thought of me as a mouse telling you a story, this story, with the whole of my heart, whispering it in your ear in order to save myself from the darkness, and to save you from the darkness, too.

Joan Didion gets credit for saying “we tell ourselves stories in order to live.” In these days, may we be like Despereaux, and tell stories not only to ourselves, but to others as well, in order to live. Make some light, reader.

___________________

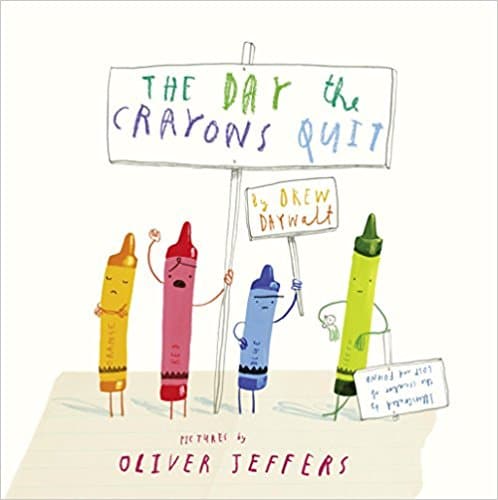

The next Children’s Book Club will meet Friday, June 8. We’ll read The Day the Crayons Quit by Drew Daywalt, illustrated by Oliver Jeffers.

Photo by Madelinetosh, Creative Commons license via Flickr. Post by LW Lindquist.

- Earth Song Poem Featured on The Slowdown!—Birds in Home Depot - February 7, 2023

- The Rapping in the Attic—Happy Holidays Fun Video! - December 21, 2022

- Video: Earth Song: A Nature Poems Experience—Enchanting! - December 6, 2022

L.L. Barkat says

I love this. 🙂

Now, I am quite curious. Did you think that Miggery didn’t have a necessary role in the story? Or, maybe, that the story gave too much play to a necessary character who somehow moved past the necessary page-count for performing her role?

I wonder how it is that stories make light for us. Perhaps it’s the act of imagination itself, or perhaps it’s somehow an assumed connection to humanity (since a story assumes a teller and a listener)?

Will Willingham says

She does play a necessary role, in a manner of sorts. It is her response to not becoming the princess that seems to facilitate their escape from the dungeon.

But then, perhaps the princess would not have wound up in the dungeon in need of rescue were it not for Miggery.

So who knows. 🙂

Story is much about connection, both between teller and listener but also between teller and listener and the characters being told about.

Will Willingham says

I think it is the intrusion. Miggery Sow inserted herself into a story I did not want to be about anyone else.

Selfish of me, yes? But there it is. 🙂

Bethany R. says

I love this idea of friends reading to each other, LW. How sweet.

Makes me think of the Friendship Initiative TSP is hoping to start on Patreon once there are 100 patrons. I don’t know if/how that would work, but wouldn’t it be cool to hear a friend record her/himself reading a poem (maybe a public domain one if copyright could be an issue?) and sending it to a friend? The voice carries something special in the way of knowing each other.

Will Willingham says

I really love that idea, Bethany. Yes, there is something about hearing the words of a story or poem in another’s voice. 🙂

Bethany says

Yes. 🙂 And then there’s all the fun in hearing where one chooses to pause, how they accent words, and how they close a line out.

Megan Willome says

LW, I’m thinking about expectations and story. This is a fairy tale (albeit a new one), and I come to fairy tales with certain expectations. You point out that at every turn, DiCamillo subverts our expectations of the story. I think that happened for you and me in different ways. So I’m now putting myself in DiCamillo’s writing shoes (to the degree I can), wondering what she was thinking as she let this story unfold.

The parts about soup were my absolute favorites. The Cook says, “And when times are terrible, soup is the answer. Don’t it smell like an answer?” Yes, it sure does.

Katie says

LOVE! This post, LW! & the comments LL, Bethany, Megan:)

Eager to chime in, but alas, the holiday weekend activities await!

More later!