Some 40 miles southwest of St. Louis is the Missouri Botanical Gardens’ Shaw Nature Reserve, more than 2,400 acres of forest, prairie, woodlands, and trails. It was first utilized in the 1930s, when air pollution became so bad in the city of St. Louis that the Botanical Gardens moved endangered plants out to “the arboretum,” which is what St. Louisans still call the reserve.

The gravel bar on the Meramec River at the Shaw Nature Reserve

On most days, it’s difficult to find a crowd at the reserve. One can walk the trails and perhaps pass one or two or perhaps as many as three people. Many times, I’ve walked the five-mile-round-trip river trail and not seen a single person or heard a single human noise other than the sound of my feet on the gravel path. The trail ends at the Meramec River, and one can walk out on the gravel sand bars and simply watch the river flow.

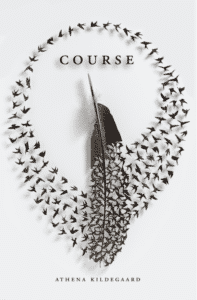

The reserve is a kind of natural sanctuary. It is that idea of natural sanctuary that permeates the 64 poems of Course by Athena Kildegaard. In quietly profound ways, she considers the natural landscape and its inhabitants. More than ask questions, she simply listens to what she hears. It may be deer, a snake, a raccoon, snow geese, herons, flowers, or blackbirds, but Kildegaard listens to them all. And she listens to the river.

Nothing Stays the Same on the River

surge high

past the sloughs

and are gone.

Swallows fall

From the bridge’s eaves.

They skim for bugs

then return

to their early nests—

crimped clay wombs

or eye sacs—

pockets into which

the swallows

reach wormy beaks.

The river has muscled

the banks right up

to where salyx

shiver down pollen.

Athena Kildegaard

What she brings is the eye and the ear of the naturalist. Even when she speaks of people and the memories of family vacations, it’s the naturalist speaking, keenly aware of how the landscape and nature shape the people who live there. A particularly powerful poem in the collection is “The River Speaks to My Mother,” in which the poet turns natural images into a description of the maternal.

Kildegaard, a lecturer at the University of Minnesota, has taught English composition, environmental ethics, and creative writing. She is the author of four previous collections of poetry: Rare Momentum (2006); Bodies of Light (2011); Cloves & Honey: Love Poems (2012); and Ventriloquy (2016). She’s received grants from the Lake Region Arts Council (LRAC) and the Minnesota State Arts Board and the 2011 LRAC/McKnight Fellowship.

Course is a poetry collection, but it is also a place, a place to watch and listen to nature and the landscape. It is also a place to find sanctuary.

Related:

Poetic Voices: Elizabeth Onusko and Athena Kildegaard

Photo by Jeffrey, Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post by Glynn Young, author of the novels Dancing Priest, A Light Shining, and the newly published Dancing King, and Poetry at Work.

__________________________

“I require all our incoming poetry students—in the MFA I direct—to buy and read this book.”

—Jeanetta Calhoun Mish

- Robert Waldron Imagines the Creation of “The Hound of Heaven” - April 8, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Luci Shaw and “An Incremental Life” - April 3, 2025

- Ben Palpant Talks with 17 Poets About, Well, Poetry - April 1, 2025

lorrie says

Absolutely lovely!!

Maureen says

“…where salyx/shiver down pollen.” Beautiful phrasing.

According to Kildegaard’s Website, some of the poems are being set to music. Would love to hear the song cycle.

The book has a beautiful cover.