Not long after we moved to St. Louis, we visited the Eugene Field House Museum. I remember an overcast day, a not-well-lit museum, and a focus more on old toys than on Eugene Field, the man once called “the poet laureate of childhood.” And I remember a small story about the museum—it had been saved by schoolchildren.

The museum sits at what was originally known as 634 S. Fifth St. and is now known as South Broadway. It is just south of Busch Stadium, on the southern edge of downtown. Built about 1845, the row house was one of 12 known as Walsh’s Row. Attorney Roswell Field, who represented his law firm’s janitor, Dred Scott, in the landmark Supreme Court case, moved his wife and baby son Eugene there in 1851. A second son, Roswell, came shortly after. When Eugene was six, his mother died, and his father sent both boys to live with a cousin in Amherst, Mass.

Walsh Row on South Fifth Street in St. Louis

When Eugene was 18, his father died. He attended three colleges, including the University of Missouri at Columbia, but never graduated. At 21, he received his share of his father’s estate, went to Europe, and spent it. Two years later, he returned, got married, and went to work for a St. Louis newspaper. He worked for a newspaper in Denver until he was enticed to Chicago, where he spent the rest of his relatively short life, writing a newspaper column called “Sharps and Flats” that became famous.

His columns covered all kinds of topics; they often included poems (newspapers published poems in this period and well into the 20th century). In the late 1880s, he included a child’s poem in a column, inadvertently launching his career as “the poet of childhood.”

All of Field’s poems, and virtually everything else he wrote and published, first saw light of day in a newspaper. But poems like “Wynken, Blynken, and Nod” were universally loved and would be read to and by generations of children. I can remember my mother read it and “The Duel” (aka “The Gingham Dog and the Calico Cat”) to me when I was a young child in the early 1950s.

Wynken, Blynken, and Nod

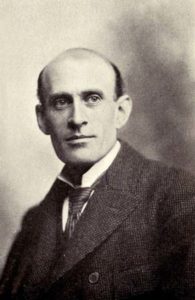

Eugene Field

Wynken, Blynken, and Nod one night

Sailed off in a wooden shoe —

Sailed on a river of crystal light,

Into a sea of dew.

“Where are you going, and what do you wish?”

The old moon asked the three.

“We have come to fish for the herring fish

That live in this beautiful sea;

Nets of silver and gold have we!”

Said Wynken, Blynken, and Nod.

The old moon laughed and sang a song,

As they rocked in the wooden shoe,

And the wind that sped them all night long

Ruffled the waves of dew.

The little stars were the herring fish

That lived in that beautiful sea —

“Now cast your nets wherever you wish —

Never afraid are we”;

So cried the stars to the fishermen three:

Wynken, Blynken, and Nod.

The statue of Wynken, Blynken, and Nod in Denver was originally in a fountain.

All night long their nets they threw

To the stars in the twinkling foam —

Then down from the skies came the wooden shoe,

Bringing the fishermen home;

‘Twas all so pretty a sail

it seemed

As if it could not be,

And some folks thought ’twas a dream they’d dreamed

Of sailing that beautiful sea —

But I shall name you the fishermen three:

Wynken, Blynken, and Nod.

Wynken and Blynken are two little eyes,

And Nod is a little head,

And the wooden shoe that sailed the skies

Is a wee one’s trundle-bed.

So shut your eyes while mother sings

Of wonderful sights that be,

And you shall see the beautiful things

As you rock in the misty sea,

Where the old shoe rocked the fishermen three:

Wynken, Blynken, and Nod.

Field began to publish both his poems and his columns as books. The books included a collection of songs, Hoosier Lyrics: short stories, sketches, columns, and poetry for both adults and children. His output was remarkable, but he is best remembered for his children’s poems. He died relatively young, at age 45 in 1895, of heart failure.

The Eugene Field House Museum today

In 1902, a memorial plaque was affixed to the house in St. Louis. Mark Twain spoke at the dedication ceremony, and was interrupted by Eugene’s brother Roswell, who pointed out that Eugene was not born in the house, as Twain had just said. Twain shrugged it off and said it was still the official birthplace.

The St. Louis Board of Education was eventually given ownership of the house and opened a museum there in 1930. But within a few years, area development threatened destruction of the entire block. A local newspaper columnist began a campaign to save the Field House, and the schoolchildren of St. Louis collected and contributed $2,000 in pennies, saving the structure—and this during the Great Depression. In the 1960s, ownership was transferred to the Landmarks Association, which continued to operate it as a small museum.

In 2015, a capital campaign raised $2.4 million to refurbish the Eugene Field House, and also add a garden and a one-story wing extension for exhibit space, a library for rare books, and offices. The museum celebrates not only the poet and childhood but also the history of toys; it has both permanent and rotating exhibits.

Roswell Field’s study in the house

Surprisingly, there are extraordinarily few biographies of this well-known and -loved poet. His close friend and fellow Chicago newspaperman Slason Thompson (1849-1935) wrote a two-volume biography, Eugene Field: A Study in Heredity and Contradictions, in 1901, and followed it up with Eugene Field: The Poet of Childhood in 1926. I’ve read the 1926 biography, and it is as old-fashioned (as in “warmly admiring”) as it is charming. Thompson knew his subject and had insights only a friend and fellow journalist would have.

Thompson also edited a published quite a few of Field’s collections, including Sharps and Flats. But other than a small biographical work published in the 1990s, you’re hard-pressed to find a recent book-length biography of the man’s life.

But the schoolchildren didn’t forget him. Field has had countless schools named after him across the country.

The dining room in the Eugene Field House Museum

Denver makes a claim on him as well, with a sculpture of Wynken, Blynken, and Nod in Washington Park and even its own Eugene Field House, which he and his family lived in while he worked there. Chicago’s Lincoln Park has a statue called “The Dream Lady,” which is actually the poem by Field entitled “The Rock-a-By Lady from Hush-a-By Street.” And Wellsboro, Pennsylvania, has a duplicate statue of the one in Denver. Imagine creating a statue for a poem today; Field has two.

But St. Louis is home. He lived here for a few short years as a child and then as a newspaperman. He felt more connected to New England and Chicago, but it was St. Louis that memorialized him, saved his house, and made a small gem of a museum.

It may be that we St. Louisans look backward more than forward. It may be that we remember our mothers reading “Wynken, Blynken, and Nod.” Or it may be that we maintain our childhood hearts, and we’re still mystified by the disappearances of the gingham dog and the calico cat. Did they really eat each other?

Photo by Pai Shih, Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post by Glynn Young, author of the novels Dancing Priest, A Light Shining, and the newly published Dancing King, and Poetry at Work.

__________________________

“I require all our incoming poetry students—in the MFA I direct—to buy and read this book.”

—Jeanetta Calhoun Mish

- Poets and Poems: Siân Killingsworth and “Hiraeth” - March 25, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Donna Hilbert and “Gravity” - March 20, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Emily Patterson and “So Much Tending Remains” - March 18, 2025

Megan Willome says

I knew the poems; did not know the name Eugene Field. Thank you.

Glynn says

What I find fascinating is that virtually all of poems were first unlisted in a newspaper. For much of the 19th century, and well into the 20th, Poetry was a staple offering of the daily newspaper.

Donna Falcone says

I can’t read Wynkin, Blynkin, and Nod without hearing the music of the song (which is how I came to know the poem). Love this, Glynn.