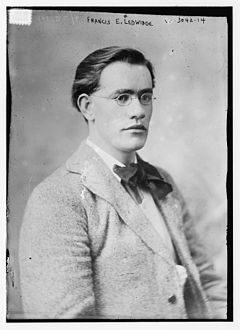

Francis Ledwidge (1887-1917) has not been one of the better known poets of World War I. At first glance, this seems puzzling.

He saw action at Gallipoli, in the Balkans, and in the trenches in France and Flanders. His first collection of poetry was published in 1914, entitled Songs of the Fields. A second was being prepared for publication when he was killed during the Third Battle of Ypres (also known as Passchendaele) on July 31, 1917, just shy of his 30th birthday. He was known, rightly or wrongly, as the “peasant poet,” which did him some injustice but which also helped to sell his poems and his poetry book. He didn’t come from the British upper or upper middle class, like so many of the war poets, but his lack of reputation wasn’t a class thing.

Instead, it was a political thing. Ledwidge was Irish, and an Irishman who volunteered for the British Army. He was also an Irish Nationalist, but not like his more radical countrymen. He believed that fighting for Britain against the Germans would help Ireland gain independence. The fact that he was Irish didn’t help him or his reputation with the British, and the fact that he fought for the British didn’t help his reputation with the Irish.

What ultimately saved his reputation in his own country was a single poem, written in honor of Thomas MacDonagh, the Irish activist and poet who was one of the leaders of the Easter Rising in 1916 and executed by a British firing squad in May 1916.

Lament for Thomas MacDonagh

Francis Ledwidge

He shall not hear the bittern cry

In the wild sky, where he is lain,

Nor voices of the sweeter birds

Above the wailing of the rain.

Nor shall he know when loud March blows

Thro’ slanting snows her fanfare shrill,

Blowing to flame the golden cup

Of many an upset daffodil.

But when the Dark Cow leaves the moor,

And pastures poor with greedy weeds,

Perhaps he’ll hear her low at morn

Lifting her horn in pleasant meads.

Ledwidge’s story and poetry were too good to leave in obscurity. In 1972, Alice Curtayne wrote what is still considered an outstanding biography of Ledwidge, simply entitled Francis Ledwidge: A Life of a Poet (it was republished last year for the 100th anniversary of his death). The second collection of his poetry, Songs of Peace, was published, followed by a third and final volume, Last Songs. Decades later, The Complete Poems of Francis Ledwidge was published.

Ledwidge’s poems are strongly influenced by his understanding of and experience in nature, which might be expected for a man who grew up in rural Ireland and had no college education. But he also writes of war, and lost love, and his poem for MacDonagh speaks to his ardent desire for Irish independence.

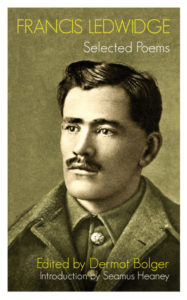

Selected Poems of Francis Ledwidge is a fine introduction to a poet who deserves to be better known, and who stands as an example of what can happen when a poet doesn’t follow the expected narrative but instead follows his own heart.

Related:

Francis Ledwidge: Farm labourer to war poet – The Irish Times

Photo by pbkwee,Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post by Glynn Young, author of the novels Dancing Priest, A Light Shining, and the newly published Dancing King, and Poetry at Work.

__________________________

“I require all our incoming poetry students-in the MFA I direct-to buy and read this book.”

-Jeanetta Calhoun Mish

- Poets and Poems: Sandra Marchetti and “Diorama” - April 24, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Christina Cook and “Roaming the Labyrinth” - April 22, 2025

- Longfellow’s “Paul Revere’s Ride”: Creating a National Legend - April 17, 2025

Donna Falcone says

I always learn so much from your pieces, Glynn.

His poem sang out like a song in my mind – and I could hear the steady beat of the Irish Bodrham…. this line really caught me – the way he shows us that war even hurts the daffodils – we hardly ever even think of the daffodils, do we?

Blowing to flame the golden cup

Of many an upset daffodil.

Glynn says

Donna, I’m so glad – and what a nice thing to say!

I’ve been watching the daffodils in our garden poking their heads up through the soil (followed by the tulips, hyacinths, and English bluebells). Everything is full of promise and hope.

Marilyn Yocum says

Agree, agree, agree, Donna. That poem is marvelous!

Marilyn Yocum says

As a few TSPoetry people know because I admitted it in a workshop once, I have a weakness for Irish poets, and ‘weakness’ is too weak a word. It might be genetic, I don’t know, but I go weak in the knees over them. And now here’s another. Coming soon to a mailbox near me: A bunch more books. Local forecast: I will be up to my ears in Ledwidge all spring and summer. 🙂

Great post, Glynn! So interesting.

Glynn says

Marilyn, thank you!

The World War I period produced a rather astounding number of good poets. But it wasn’t just the war. Changes in British (and by extension Irish) education and schools in the 1870s resulted in an expansion of literacy, literature, and writing. Unlike many of his English poetic counterparts, Ledwidge came from a working class background. Then again, writing and literature (and poetry) has historically been incredibly important to the Irish. (I don’t know if they still are, but authors in Ireland have been exempt from income tax.)

Katie says

Really appreciate your posts Glynn.

After reading this latest one, I back tracked to the other posts you’ve made on WWI poets. They are all excellent.

Here is a cinquain I wrote after reading and following links:

The Lost

Generation

Disoriented men

Wandering, directionless souls

Aimless.

Gratefully,

Katie

Glynn says

Katie – thanks for the note. And for the cinquain!

The last four years have been filled with books and articles about the poets of World War I. Few wars, if any, produced the outpouring of poetry that this war did. In addition to the changes in education i mentioned in a comment above, the war years coincided with a general interest that found poetry in daily newspapers, magazines, and other media, so there was a demand and markets for poetry. Few newspapers today print poems; those that do are often British.

Katie says

Glynn, You’re so welcome. I would love to see poetry become widely published here as it was then in Britain. Here is another cinquain I wrote about WWI:

The war

The Great War to

End all wars, World War I

Trench warfare, Lost Generation

Poppies.

Marilyn Yocum says

Searching for the “like” button on here, Katie. Nice cinquains.

Katie says

🙂 Thank you, Marilyn.

Michele Morin says

I’m always thrilled to learn about a new-to-me poet, and this post came with background as well as a gorgeous sample of his work.

Thanks, Glynn!