Each day when I come to work, I pull a white card the size of a credit card from my wallet and hold it up to a machine until it beeps. “Callie Feyen, Para-pro” pops up, and I push another button to tell the machine I’m here.

The title of my position is At-Risk Literacy Specialist, and it falls under the para-professional category in the school district where I work. The first time I clocked in and read the word “para,” I looked it up in the dictionary. I learned it is a “word-forming element.”

I like that phrase. It suggests something that wasn’t there can now exist.

“Nobody really knows what it is you’re going to do,” my principal told me the first day I started.

“Perfect,” I thought as I took a look around the library where I would work. “I get to decide for myself.”

On a cart waiting to be shelved sat stacks of books on their sides; some of them had fallen open. It was as though they were smiling at me, welcoming me into their world, waiting to see what I would do once I stepped in.

A two-foot-tall cutout of Max dancing with his wild things stood tall on the shelf with the S books. I walked to where he was, reached to lift him up and have a closer look, then pulled the sleeve of my yellow winter jacket over my hand and wiped cobwebs from Max’s head and arms. I turned him around looking for any tears that might need to be mended. He was fine. He could still dance.

“Let the wild rumpus begin,” I whispered as I put Max back on the shelf.

The Rumpus Begins

Today, I will see a group of fifth-graders. We are reading Holes by Louis Sachar, and this afternoon I will read my favorite part of the story, when the Warden speaks for the first time.

Nobody expects the Warden to be a woman. For almost 70 pages, we’d been reading about somebody tough, somebody you don’t mess with, somebody who “owns the shade” created by two trees in an otherwise dehydrated lake. Of course, we eventually feel sheepish because we believed that someone with a personality like that would be a man, and it’s a collective delight to learn she isn’t. I love to hear the gasps when she steps out of the Jeep with her wild red hair and black cowboy boots with turquoise studs (a pair of shoes, I must admit, I wouldn’t mind owning).

I know she’s a villain, but I like the Warden. She is cool and menacing, and reading her first scene is one of my guilty pleasures. I like to try on her personality. It’s like wearing a mink coat — I’d never actually buy one and probably I’d never have the heart to put one on, but what would I act like if I did?

In the scene, the Warden doesn’t say much. Mostly, she asks a two-word question — “Excuse me?” — that I’m not sure she really wants an answer to. Asking it brings with it a flood of frantic excuses.

My plan after I read this scene to the children is to play a game I made up with them called, “Excuse Me?” I wrote several statements on index cards: “I don’t like spaghetti,” “I think I’m a robot,” and “I lost your dog.” One student will say the statement to another, and the only thing the other student can say is, “Excuse me?”

The trick, then, is to use subtext to show emotion, whether the question evokes annoyance, shock, joy, or whatever. It will be an exercise in make-believe; students get to see what it feels like to be the Warden. What will they do when they try on her personality?

It’s also an exercise in helping the students see how they can make dialogue work harder in their writing. If all a person can say is, “Excuse me?” how else will they communicate how they are feeling? Will their eyes bug out? Will they drop something? Will they put their hand on a hip? All those actions can be incorporated into a story.

Finally, once we’ve pretended for a bit, I will have students write their own scene between two characters, one of whom is only allowed to say, “Excuse me?”

We start class each week in a space I call “the pit.” It’s filled with pillows, and in the center is a set of pretend fire logs and fire. I think of it as a giant prompt: Let’s sit a while in a world that is not our own and see what we can find out about ourselves.

I think that’s what I’m doing with the Warden and Max and all the characters in books I read. I’m trying on their personalities for a time. The books I read are my “paras,” my word-forming elements. They show me something that wasn’t there before that can now exist. This is what I want the kids who come into the library to know — how to open up a book and open up a part of themselves.

It’s been almost 20 years since I first read this scene to a class, but the magic has not worn off. I can feel the surprise and the nervous silence when the Warden makes herself known and then heard. She is just as commanding as she was when I first read her.

How I Get the Kids Writing

I put down the book when the chapter ends and with a sly grin, I say, “Let’s all pretend to be the Warden.” I get thirty sly grins back. I explain my “Excuse me” game, and hands shoot up to give it a try.

As the students act, I point out facial expressions, gestures, posture. “You can use all this in your writing,” I encourage them.

When it’s time to write, the room quiets, save for pencils scratching quickly on paper. I relish that sound.

After a while one student raises his hand and asks, “Can we share?” Several students look up from their writing, eager to share what they have written as well.

I’m thrilled they want to read their writing out loud. It means they’ll have a chance to play with tone, hear themselves, and catch what they might’ve missed in the excitement of trying to write down an idea.

“Yes,” I say, “let’s share.”

So they do. One after another they rush to my side with crinkly papers in their hands. I smile and laugh and say, “Good job,” as I listen to how they’ve taken a part of the Warden and tried her on for themselves.

A girl with short blond hair and glasses, who’s wearing a pair of mustard yellow jeans that I’ve coveted since I first saw her wearing them, is the last to read.

“I wrote about hating Harry Potter,” she whispers to me, then quickly adds, “but I don’t hate Harry Potter. I wanted to write something shocking so I could get the ‘Excuse me’ part right.” She looks down at her paper and seems to read it over frantically, then looks up at me again.

“This will be really hard for me to read.”

“It’s scary to be something you’re not,” I tell her. “I love Harry Potter, too. This would be difficult for me to read.”

She nods, but doesn’t make any attempt to face her audience.

“It’s okay,” I whisper. “You’re just pretending.”

“Okay,” she says and turns towards her classmates to read. Her voice is strong and confident, not at all shaky, like when she whispered what felt like a confession moments ago. She entertains the class with her work, and as I listen, I start to feel sorry for the Warden. This scene where she is introduced is her best scene. Afterward, she reveals herself to be more evil with every turn of the page. At some point in her life she came to believe she could only be one thing.

While Holes is fiction, when we choose in real life to believe we are only one thing, it is tragic. The Warden’s identity is built on searching for and protecting something that was never hers to begin with. She loses herself in that search. She revels too long with the wild beasts she creates, and when she wants something more, something different, when she wants to go home and the beasts threaten to eat her up because they love her so, she believes them. And she stays.

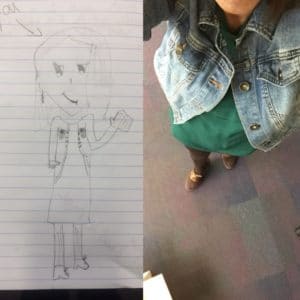

When the girl finishes reading, she pulls a folded-up piece of paper from the pocket of her jeans. “For you,” she says. “This is you.”

I unfold the piece of paper and look at her sketch. Indeed, it is me. She’s drawn me holding Holes and smiling with a hand in the air as though I’m teaching. I’m wearing a green dress, brown tights, brown saddle shoes with a chunky heel, and a jeans jacket. The dress is one of my favorites because there are abundant ways to wear it. The dress can take on a plethora of forms, tones, and moods. What the dress is never changes. What it can do does.

“Thank you,” I tell her, smiling. “This is perfect.”

What the Dress Offered During Dark Days

I almost threw that dress in the garbage last year. I’d decided one morning that most of my wardrobe was too frivolous, too whimsical, too loud, and I went through my closet, yanking clothes from their hangers and feeling like one of Cinderella’s evil stepsisters. No longer could the frivolous, whimsical girl exist. She needed to leave.

When I reached for the dress though, I paused because the fabric was light. Not weak, but uncomplicated, familiar, and friendly.

Maybe I can stay? the dress seemed to suggest, its dark, green fabric twined in my fingers.

“Excuse me?” I said, dropping my arm, but not letting go of the dress.

Navy blue tights and your light brown boots with a matching belt? Black leggings and black boots? Your yellow shoes and matching chevron scarf? the dress whispered.

“Excuse me?” I said again, lifting it from the hanger, dropping my garbage bag and walking with the dress to the full-length mirror in our bedroom. I wouldn’t put it on. I’d just hold it against myself to see.

Let me stay. Give me another chance. Don’t be scared.

It wasn’t the dress speaking, of course. It was the girl in the mirror holding the dress, reflecting what I hoped was still there.

“Okay,” I said, slipping the dress back on its hanger. “Maybe.” I hung it carefully back in the closet and picked up my garbage bag, hoping that because I chose to let the dress stay, something that wasn’t there could begin to exist.

The Dress, One Year Later

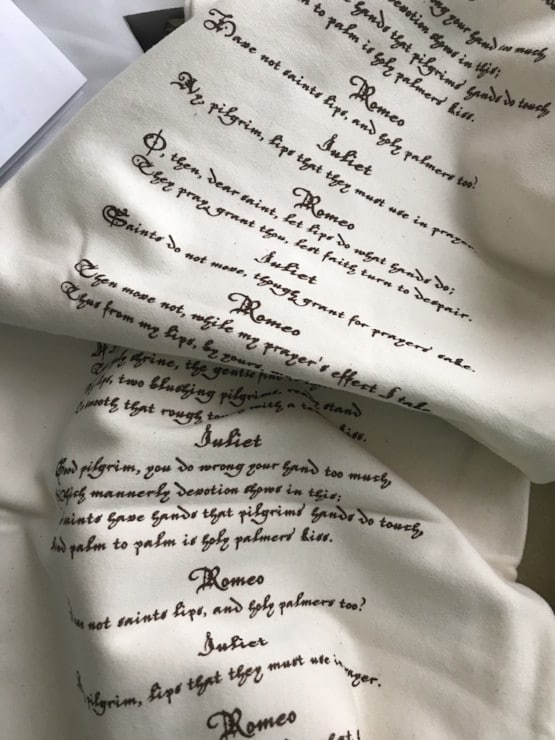

This week, when The Teacher Diaries: Romeo & Juliet launched, is the same week that I started this new job last year and walked into the library to dust off ol’ Max from the shelves. The weekend before I started that job was the same weekend I shoved all those clothes into a bag, but kept the green dress.

Now, one year later, I’m so glad that I let the dress speak during what were dark days for me. I’m glad I agreed to pretend in front of the mirror. And that, twelve months hence, I wore the dress to school on the day my book released—an unexpected book that has hope and courage at its very core.

What scarf to go with? The dress and I agreed: Romeo and Juliet. Then we danced on off to school, where a little girl saw the magic and penciled it down.

Photo by Steve Corey, Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post by Callie Feyen, author of The Teacher Diaries: Romeo & Juliet.

Browse more teaching resources

Callie Feyen’s warm, funny, and deeply felt reflections on teaching Romeo and Juliet to eighth graders took me back to that moment where my own junior high teacher’s line-by-line slog through the play led to my conversion experience to the wonders of great literature. Here is a book that will not only encourage and inspire other teachers but thrill anyone who knows how profoundly literature can awaken and shape the soul.

—Gregory Wolfe, Editor, Image

- Poetry Prompt: Courage to Follow - July 24, 2023

- Poetry Prompt: Being a Pilgrim and a Martha Stewart Homemaker - July 10, 2023

- Poetry Prompt: Monarch Butterfly’s Wildflower - June 19, 2023

Bethany R. says

Love this piece (and your outfit) Callie, thanks for crafting it.

Jerry says

It’s hopeful to hear again from another human that imagination isn’t dead, and in fact, it is shared with young imaginations to reproduce itself uniquely over and over. Praise be!

L.L. Barkat says

I like the idea of listening to objects. I think it’s the heart of great writing, to be able to “see and hear” that which is actually inanimate. Engaging in a conversation with such objects? All the better. A fun exercise in Imagination.

Then Imagination fuels hope, and hope spurs action.

Sandra Heska King says

Good heavens, Callie. I was right there with you–feeling a little sad as you dusted off Max with your yellow sleeve to wanting to hug that girl in the yellow jeans to wondering if you’ve ever worn that green dress with your yellow shoes. Your words are sunshine.