During an in-service training about how to help children with their writing, I heard Lucy Calkins tell a story about a writing conference with a boy who wrote about a trip to an amusement park. His story went something like this: Me and my dad went to Great America. I went on a roller coaster. I drank pop.

We teachers simultaneously cringed and chuckled, knowing the work that needed to be done in order to pull out more of the story. I was already in correcting mode, imagining going over the draft with a red pen: “More detail!” I’d command. I was considering stories I could recommend about dads and sons so this boy could get some ideas about how to frame his story.

Lucy did none of those things. Instead she talked to the boy about his story.

“You rode a rollercoaster? Wow! That must’ve been fun!”

“Your dad took you? How nice!”

“You got to drink pop? What a treat!”

Hearing his story enthusiastically told back to him, the boy told Lucy more — it was a fun day; his dad doesn’t come by so much.

“I still have the can,” the boy told Lucy, referring to the can of pop he drank at the amusement park.

I wrote his words on an index card and taped it to my desk. “I still have the can,” was the first thing I looked at every morning, and since it sat in the center of my desk, I saw it frequently. It reminded me that before I get out that red pen, I must first listen.

I don’t know many of us who admit to writing with ease, especially when we come to a point in a story when there’s conflict. Writing about pain or shame or anger is agonizing, and that’s for those of us who’ve been writing for a while and have built up our endurance muscles. How much harder must it be for students who are still learning their letters or sentence structure or any number of literacy skills.

I’m not sure there is an easy way to teach writing, but I think listening is an essential step to building trust with children — no matter their age. And trust leads to better storytelling. Recently, I tried to build trust with a group of kindergarteners and first-graders by reading and then writing about Ezra Jack Keats’ The Snowy Day.

Before we read the book, I asked the students what they like to do in the snow. Some of the most popular responses were “make snowmen and snow angels,” “have snowball fights,” “drink hot chocolate,” and “put on snow pants,” and I agreed that those were some of my favorite things, too.

“Sledding!” they said, some of them throwing their arms in the air and smiling at a memory. “I forgot! Yeah! I like sledding, too!”

It was a casual conversation, but it was important because I established trust, and if I’m going to help these wide-eyed children with their words, I must have their trust. I prepped them to write their own stories, no matter how jagged or rough those stories might be. I wanted them to believe they could do it.

When I’m reading aloud to children, I discuss the story as we go. I think this is important because talking about the story’s arc, characters, and setting provides context, and context allows us to relate. I love Keats’ decision in The Snowy Day to set Peter’s snow adventures in a city, and my favorite part is when Peter asks his friend across the hallway to join him in the snow.

Peter lives in an apartment. It’s a seemingly small detail, but when I was a new mama, living on the third floor of a condo building and my toddler girls had their faces and hands pressed against the windows when the first flakes fell, it was Peter who reminded me that playing in the snow is for everyone. He showed me that it isn’t a matter of whether or not I like snow. The question is, do I have enough imagination to play in it?

And so it goes with stories. Seeing a character try something new, explore her world, or stand up for what he believes allows us to connect and think, I could do that, too. Reading gives us a safe world to try on experiences and even personalities we might not explore otherwise.

“Watch what Peter does throughout the story and see if you do the same things. What are some things you do differently?” I asked the children as I began to read.

And so they told me. Students pointed to the pages and said, “I’ve done that!” or, “That’s happened to me, too!” Some said, “I can’t wait to try that.”

We took our experiences with snow and put ourselves in Peter’s story. Perhaps a good term for this exercise could be “reciprocal storytelling” because listening helps us empathize, and in turn, find ourselves in our own stories.

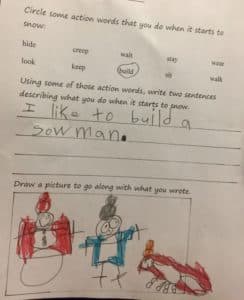

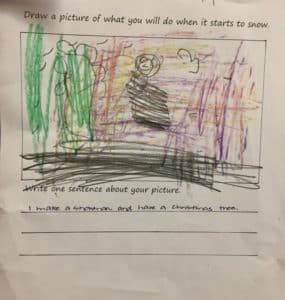

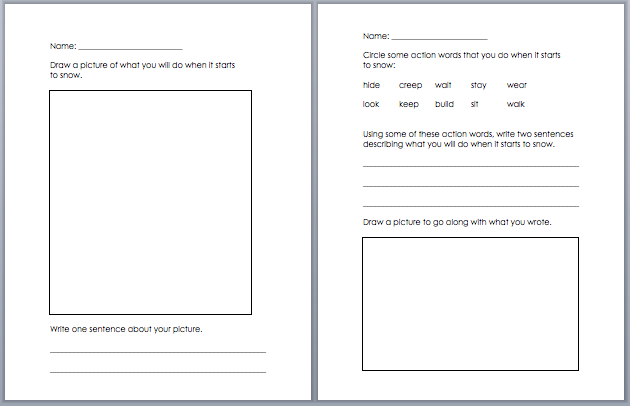

After we read the book, I passed out a worksheet and asked students to draw a picture of what they liked to do in the snow and write one sentence about their picture. For the first-graders, I typed a handful of snow words they might like to use. For example, instead of “make a snowman,” they could use the word “build.”

For many of the kindergartners, even writing their own name, was overwhelming. But they still had a story to tell — they raised their stories and illustrations to my face and said, “Look! Here I am in the snow!”

I knelt next to the table where they sat, took a pen from my pocket, and said, “Tell me all about it!”

“This is me and my sister throwing snowballs,” one student narrated. She was quiet while I wrote, watching my hand push the pen across the page. I was careful to write slowly and neatly, and I said the words as I wrote them.

“I miss my sister,” she whispered to me.

“I bet,” I whispered back. “It looks like you are having a lot of fun in this story.”

She nodded, and I asked her if she would like me to write that she missed her sister. She nodded again, and so I wrote that down.

I wanted to ask more: Why does she miss her sister? Where is her sister? Is she at college? Dead? I don’t know how much to push. Writing is mysterious. The story that needs to be told doesn’t always reveal itself until further down the road. My hope with this child is that I cemented a memory in her mind of a person who listened attentively so she could keep telling the story when she is ready. When the time is right, I hope she pulls up that memory, trusting herself.

Another boy showed me his picture — a stick figure and a snowman with a pink border. “What’s going on in this story?” I asked.

“Hmph,” he said, crossing his arms and furrowing his brow. He was feeling shy or angry or maybe ashamed. I don’t know, and I’m not sure if he told me I’d know how to convey the emotion. So I looked at his picture again.

“It looks like you’re outside with a snowman,” I said.

“I’m throwing snow,” he said, sharply.

I wrote that down.

He gave me more. “I’m throwing snow and making a snowman.”

“It’s a nice snowman,” I said when I finished writing.

“He is not moving,” the little boy said, uncrossing his arms and stepping closer to me. He took my hand and pushed my pen down so I couldn’t write. He picked up his paper and studied it, his face softer now, his eyes wide and curious.

“We are outside,” he said quietly.

What memory did this child hold? What did he see? I thought of Peter, when he put the snowball in his pocket and brought it inside for safe-keeping, but it melted once he came home. Peter was so sad. Was this boy sad as well, seeing something he thought was gone? I worried that, like the little girl who whispered to me that she missed her sister or the boy who told Lucy he still had the can, if this boy was holding on to this mysterious memory with both hands. Maybe he was doing all he could do for one day.

“Would you like me to write down that you are outside with your snowman?” I asked.

He looked at me, a mixture of surprise and maybe irritation, and I felt bad that I pulled him out of his memory. He handed me the paper and nodded.

“We are outside,” I wrote.

“Thank you,” he said.

“You are welcome,” I said, putting the cap back on my pen.

In The Snowy Day, Peter dreams all the snow melts, but when he wakes up, he sees “his dream is gone,” and he calls to his friend across the hall to come outside with him and play in the new snow.

New adventures to be had. New memories to build. New words to form.

I am here to listen.

Photo by Gabriel Caparó, Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post, pictures, and worksheets by Callie Feyen. Reprinted with permission.

Browse more about The Snowy Day

Browse more teaching resources

_______________

Want to use Callie Feyen’s worksheets with your students? Click here!

- Poetry Prompt: Courage to Follow - July 24, 2023

- Poetry Prompt: Being a Pilgrim and a Martha Stewart Homemaker - July 10, 2023

- Poetry Prompt: Monarch Butterfly’s Wildflower - June 19, 2023

L.L. Barkat says

I think it is very telling that he pushed the pen down, and there’s a part of me that wishes early educators as a whole would “push the pen down” in favor of lifting the hands in play.

Recently, one of my college professor friends told me she and her colleagues have been asking, “What in the world is going on in early childhood education?”—because the writing skills of their students have degraded so severely over the years of getting a new batch of students to teach each year.

What I told her, believe it or not, is that I think the writing workshop is partly to blame. Because, while I understand the spirit of the workshop, I think it’s eclipsing the natural narrative capabilities of children, narrowing their expansive possibilities into the tip of a pen that does not write fast enough—never can write fast enough—to capture what’s on their minds.

Which isn’t to say that I think children shouldn’t write. But I’d love to see the narrative/composition part broken out from the handwriting part, so that true composition skills can be built in the ways children work best… through hours of pretend play and storying-aloud.

As you know, I tested this theory (with no small bit of anxiety!) when educating my own kids, by letting them “write” by storying-aloud with blocks and dolls and play clothes, for many years. Daily handwriting that focused on copy work of marvelous quotes allowed them to build up the necessary fine motor skills and get the structure of excellent writing into their hands/minds. Daily read alouds also put the structure of excellent writing into their minds. Today, they are two of the best writers I know, and the youngest (who struggled with the mechanics of learning to read and write—so, instead, she *listened* to hundreds of hours of stories on CD) is such a seamless writer that it is rare to have to change even one word of anything she pens, including journalistic pieces.

Anyway. The part of writing workshop that I wish would stay is the *listening* part you’ve so beautifully discussed here. Then I wish the listening would be extended into play, through the hands and body, rather than into the act of having to write it down.

Thoughts? What is your experience with children’s story telling when they are faced with a blank page versus a pile of blocks, a collection of dolls, or a stack of dress-up clothes? 🙂

Callie Feyen says

Yes, I can still feel that part of the story when the little boy pushed the pen down. It’s something I’ve been thinking about for a while now, especially as it feels I am in a transition period trying to figure out what it was I was good at when I taught, and what it is that makes me uncomfortable about teaching.

I think I come from a more “let’s get them playing and I’ll find a lesson from there” kind of person. I think of the first units I taught: A Wrinkle In Time, The Midwife’s Apprentice, Walk Two Moons. All of those stories were STORIES FIRST, and I wrote my lessons plans from how they reacted to the story – how we played with the story.

It’s a confusing time for me as I figure out what to do next, and whether the kind of teaching I want to do is actually the kind of teaching I should be doing. Consequently, my job is changing so that I will no longer be able to read stories to children. It’ll be all worksheet/skill-drill based due to new reading retention laws.

L.L. Barkat says

Oh, say it isn’t so!

Tell me about reading retention laws? What is it that the worksheets are meant to help the children retain?

Callie Feyen says

From what I understand, if students aren’t reading at a third grade level, by third grade, they will be retained. One of the schools I teach in doesn’t qualify for “Title 1,” which allows for two reading specialists to work in that school and help with literacy development. Because of this, they’ve decided the most important thing I can do is pull kids 3-4 at a time, and work with them in 30 minute increments. It’ll be skill and drill type of work, and I have been pretty sad about it until last night when I was reading A Wrinkle In Time with Hadley and Harper, and we got to the part where one of the Mrs. W’s was explaining the sonnet to Calvin. She talked about the very strict rules of the sonnet, but that within those rules, you can write about whatever it is you want to write about. So maybe I look at it that way. Or, maybe it’s time to go back to middle school. I’m not sure yet. You know me, I can find some creative way to stay within the rules and still add some fun in the mix. And if I can’t, well, I’ve left before.

Oh, and I think the worksheets/computer programs they are to complete are to help them learn letter sounds, etc. I respect that, I just don’t respect the way it is taught. i think it can be taught using a good story. Stories first. That’s my new motto.

Katie says

Callie,

“Stories first.” Yes!

I hope and pray those who make the decisions about how children are taught will LISTEN to teachers such as you who really are connecting with the students.

“New adventures to be had. New memories to build. New words to form. I am here to listen.” You are SO spot on with this.

Studies show that one of the best things parents can do for their children is to read to them.

By the same token, I would expect that reading stories to children in the classroom would be more beneficial than worksheets alone.

Katie

Donna Falcone says

NO! Oh Callie. That has all the earmarks of a statistician’s input and I can’t imagine a veteran teacher had anything to do with that decision. Oh my heart is coming out of my chest!

Callie Feyen says

I can say that nobody wants it this way. Everyone is all quite sad. I will say that the teachers in both schools I work in are fantastic, and all of them read out loud to their classes consistently. They’re creative and wonderful, and I was just an extension of that. Still, it’s a sad situation. I’m quite overwhelmed at the amount of work I will need to prep for, and the lack of creativity and risk-taking I’ll get to do in the coming months.

L.L. Barkat says

I’m sort of curious about the actual initiative. Is it to cancel read alouds altogether? Or is it to build reading skills using a phonics emphasis?

The thing is that learning to read is virtually impossible for about 45% of children who can’t just “pick it up” from being read to. A strong phonics approach does the trick for these children.

But, you know me: I want both. That’s what inspired the Molly and Joe series (more to come, promise): it works on a playful story-poem basis, but it’s got a phonics underpinning and so do the accompanying activities in the back of the book.

Anyway, I’d be interested to hear more about the actual initiative and its supporting materials and if it’s based on anything that the leadership has seen works in other schools (say, like the program outlined in Sunday is for the Sun, Monday is for the Moon.)

Callie Feyen says

I agree you need both phonics instruction and love of story, or just the opportunity to walk through a story. After a day of doing this new intervention, I will say it is an honor to sit down with these kids and help them with the nuts and bolts of reading.

My sadness, or frustration, comes from the way my job is organized. First, is through a grant, so who knows if it’ll be around next year, but because of the way the grant was written, I am in charge of running a library, truancy, and at-risk literacy. It’s a part-time job, with three full time responsibilities. I am physically unable to do all three. I’m not talking about doing all three well – I know I have perfection tendencies – I’m saying that there are not enough hours in the day to complete these tasks. At-Risk Literacy should be a full time job. Being a librarian should be a full time job. Truancy? Well, I have no passion for that, but that too should be full – time. It upsets me that these kids are getting scraps. They deserve the absolute best. You know I’m doing my best, but I’m in a tough situation regarding these other responsibilities.

I will say that the schools I work in know this, and this is why in one of the schools, I no longer run the library, and only focus on literacy support. I respect their decision to do this, and I appreciate that they are doing their best so that I and the students are successful.

L.L. Barkat says

I would love to hear more about the specific intervention (and I’m so glad to hear it was a good experience).

Also? Wow. Too many disparate responsibilities. I’ll say this: truancy will abate (somewhat) if reading skills rise. So you are, strangely, working on truancy… through the side door! 🙂

Callie Feyen says

We are using the Guided Reading model from Fountas and Pinnell, as model I’m familiar with because that’s how I set up my classroom when I was teaching middle school. It feels like a workshop, and it’s exploratory. At the K-1 level, the stories we use are very basic, but I’m surprised at how much the kids love them, and talk about them when we are reading them.

The other program we use is Lexia, which is 100% skill and drill. I’m not saying it’s not doing the trick – it’s just that the life sort of sucks out of me when I have to implement this part into my lessons. I’d like to find a way to make it more jazzy, I guess.

I’ve been thinking a lot about the conversation from this post, and it’s helped me name a few things that have made me uncomfortable with the situation. One, I have two much to do, and, as you know, when that happens, I get into a real funk because of course I want to do all of it, and do it well. I start saying things like, “If I just tried a little harder. If I was just more organized. If I was smarter….” The second thing that makes me sad is this reminds me of my own education, and all the worksheets I had to do because of my test scores. My teachers were kind, but this way of teaching sent the message to me that I am unable to handle chapter books, or even picture books. I have to know “all these things” before I can enjoy a book. I lived next door to a library, for crying out loud, and once I started school, I stopped going because I figured, “What’s the point? I’m too dumb to figure it out.” Twice in my life I had people tell me that wasn’t true: the very dear Mrs. Grinbard, who worked in the library, and told me about the alphabetizing of the books, and from there, I found Dear Mr. Henshaw (you know that story), and the summer I spent shelving books at the library when I was 16 and found The Princess Bride. I hid behind the bookshelves reading and reading. Laura Brown knows that story (it’s “Toast” on MYM).

I have no doubt I’m a reader. I love stories. But it FEELS like I have to fight with a truth that I don’t want to be true when I work with these kids: that I am too dumb to understand a story, and I am passing that along to them.

KMA says

I went to a conference on writing last week and the presenter, Mary Ellen Ledbetter, clarified that the best way to LISTEN to middle schoolers is to conference with them, and I thought, “That’s a great idea! Use conferencing not only for literary skills but for listening to students describe their writing process, their thoughts, and their development in their writing.”

Callie Feyen says

That’s an excellent idea. I found that in one-on-one conferencing, even when it’s on their reading or writing, things seep out that add to depth to the student-teacher relationship, and help me understand and teach better anyway. I should do this on a quarterly basis when I return to middle school teaching. Thank you!

Tiffany P says

Oh Callie… I love your writing so much. So many gems in here… Did you have a workshop with Lucy Calkins in person? I have taught her lessons in 5th grade in a title 1 school and I got frustrated because while the students were able to get deep into the writing, there was a lack of understanding because they didn’t know proper grammar and sentence structure. How does one accomplish both with students who desperately need to get their thoughts on paper in a clear way?

Callie Feyen says

Thanks, Tiffany. The workshop I took was via video, so I didn’t see her in person, though I was in several workshops with Nancie Atwell, who uses the same workshop approach.

I absolutely understand your frustration, and I know that this is something that gets the biggest pushback to using this approach. WHEN DO WE TEACH THEM GRAMMAR?!?!? I get that. And, in the last couple of years, phonics, letter identification, sentences structure, grammar…..the vital building blocks for literacy have been what’s on the minds of educators. These are necessary.

The problem is, I don’t believe they can be taught without story. So, for example, let’s say I go to a Chicago Bulls’ game in the early 80s, and let’s say I see Micheal Jordan slam dunk from the free throw line. That’s story. That will be blazed in my memory forever, and any time I hold a basketball, I will remember what I saw that day in the stands, and I will want to see if I can do it, too. Nevermind the fact that I will never be able to slam dunk (or dunk at all) like MJ. We’re talking hypothetical here. However, Jordan showed me the possibilities there are with a basketball. I can’t do that without understanding technique, right? So I have to learn to dribble. I have to……I don’t know, build up my biceps, run, learn how to jump, pass, whatever it is that will “write my own story.” So, yes, you are right – there’s this urgency in all children to tell their story, but many don’t know have the tools they need to tell it. What do we do?

Unfortunately what I’ve learned in the last couple of years being in a few different schools, is that telling stories is a luxury. Even in my daughters’ school, there is no evidence I see that shows they are getting lost in a story. That only happens at home when they are reading, or when I read to them before bed. The kind of teaching that goes on in the schools we are in is teaching without risk. Here is the standard, here is the drill, if you do these exact things and get them exactly right, you may move on to the next step. There are no questions. There is no grappling. There is no curiosity.

How do we combine mechanics with curiosity? How do we keep the urgency of both? In the school I took Calkins workshop in, the Language Arts team was committed to the workshop approach. We were not in an affluent area by any means. Truancy was an issue, as were other things that we can discuss privately if you’d like. However, the teachers and principal I worked with structured the Language Arts courses so that we were able to create a curriculum that allowed for poetry and creative writing, reading books as a class as well as individually, studying and learning vocabulary, grammar, sentence structure. It was one of the best schools I taught in. I had about 130 kids, so the grading was crazy, but we were getting it done, and it was exactly how I think Atwell and Calkins would’ve structured it. And this was a public school.

I don’t know. I don’t have the answers. I think it would behoove everyone if we all had story time every day. I think that would do us all a world of good.

Callie Feyen says

Thank you, Katie. I agree with you regarding stories doing more than worksheets. However, I guess the argument is that there is no way to measure that, which is why my job is changing now. It’s very much a Puff the Magic Dragon kind of situation. No more imagination. No more play. I’m sadly slipping into my cave with my stories.

Donna Falcone says

This is so special… and of all the favorite lines I kept highlighting and copying…. this one is my most favorite:

“Would you like me to write down that you are outside with your snowman?” I asked.

Because you asked. You sent him a world of important messages when you asked.

-this is your story, not mine, and I respect that.

-I want to know what you want to say.

-I want to know if you want others to know what you want to say, because it matters.

-you have rights.

I think the first and last bullet are boundary related, and we need a lot of conscious boundary resilience support/practice in this new world of sound bites and cellphone cameras.

I was going to say asking is the other side of the listening coin, but I suppose listening is a many sided coin.

Callie, I would love to be a fly on the wall of your classroom!

Callie Feyen says

Thanks so much, Donna. That was a really special moment. I get to have lots of those in the one school I’m in. And I agree – listening is so, so important. There doesn’t seem to be a lot of time for that in schools these days, but it feels like one of the most active things I do when I’m teaching.