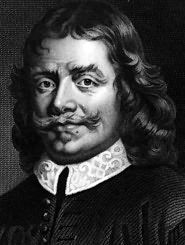

During his lifetime, the English Puritan minister and writer John Bunyan (1628-1688) wrote some 60 works, mostly collections of his sermons. After the death of Oliver Cromwell (1599-1658) and the restoration of the Stuart monarchy in 1660, Bunyan spent 12 years in prison for refusing to stop preaching.

It was during his imprisonment that he began work on his best-known work, still in print today, the allegory Pilgrim’s Progress. The work wasn’t published until 1678, six years after his release from prison.

John Bunyan

Bunyan also wrote poetry. Specifically, he wrote poetry for children. First published in 1686, his A Book for Boys and Girls, or, Country Rhimes for Children is considered to be the oldest book of poetry for children. In 1724, the work was renamed Divine Emblems, which makes it sound less for children and more for religious adults.

The poet takes a deep look at the world around him. The poems aren’t what one would associate with the word “puritanical,” nor are they all directly about religious topics. To be sure, there is a poem about the Lord’s Prayer. But there are many more poems about nature—birds flying in the sky, a lark and a fowler, trees, a meditation upon an egg, sunrise and sunset, fish and streams, and bees. Bunyan often includes references to religion and faith; he was a preacher, after all. But this poem about the time before sunrise is fairly typical of what he does.

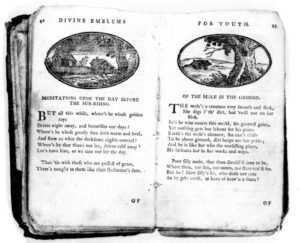

Meditations Upon the Day Before the Sun-Rising

Drives away and beautifies our days?

Where’s he whose goodly face doth warm and heal,

And show us what the darksome nights conceal?

Where’s he that thaws our ice, drives cold away?

Let’s have him, or we care not for the day.

Thus ’tis with who partakers are of grace,

There’s nought to them like their Redeemer’s face.

Bunyan meditates upon a candle, the sacraments, the sun reflections on clouds, moles, the cuckoo, the butterfly, and more. The collection includes a delightful and lengthy conversation between a sinner and a spider, in which the spider convinces the sinner of the errors of his ways.

Two pages from the original published version

These poems are not what a contemporary reader might expect for children. They are grounded in the real, physical world, drawing upon nature and everyday objects and events. The language is the language of adults; these poems do not “talk down” to children but instead assume that a typical child would hear and understand what the poems say. They also speak to behavior that children (and adults) would be familiar with, such as stealing, wearing ostentatious clothes, and showing kindness.

This particular edition includes 40 of the original copperplate drawings from the original publication.

Bunyan’s Divine Emblems open a window on a world long gone, but it is a world we can easily recognize and understand, both as adults and as children.

Photo by Phillippe Put, Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post by Glynn Young, author of the novels Dancing Priest and A Light Shining, and Poetry at Work.

__________________________

“I require all our incoming poetry students—in the MFA I direct—to buy and read this book.”

—Jeanetta Calhoun Mish

- Poets and Poems: Sandra Marchetti and “Diorama” - April 24, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Christina Cook and “Roaming the Labyrinth” - April 22, 2025

- Longfellow’s “Paul Revere’s Ride”: Creating a National Legend - April 17, 2025

Bethany R. says

I’ve read Pilgrim’s Progress, but not this collection. Thanks for highlighting it here.

I can’t imagine what it must have been like to spend 12 years in a 17th-century prison and still find the desire and tenderness to write poetry for children. How beautiful. I wonder what his main inspiration for the collection was.

Megan Willome says

This is so interesting, Glynn. I recently read a book that talked about early Christian morality tales for children, but this sounds quite different in tone.