Is it possible I graduated from high school without having memorized at least some poetry? I don’t remember doing so. I do remember my best friend once said her favorite poet was e. e. cummings. I don’t remember why, except maybe for his love of the lowercase and funky forms and the way he played with words and punctuation. I faintly recall having read these lines from i thank You God for most this amazing:

i thank You God for most this amazing

day: for the leaping greenly spirits of trees

and a blue true dream of sky; and for everything

which is natural which is infinite which is yes.

I don’t remember memorizing the poem. It seems I may have, though.

Some say cummings was the second most widely read poet in the United States (following closely behind Robert Frost, who was twenty years his senior) when he died in 1962, five years before I clutched my diploma. While I’ve forgotten a lot about those years, I do recall a fear of poetry, and letting my eyes roam around the room or stare at my book while I mentally begged the teacher not to call on me in class.

Yet if I really was so scared, why did I torture myself by enrolling in an English Literature class at the University of South Florida as a young adult? This makes it all the more remarkable that now, fifty years later, I’m saying an infinite yes to poetry—and that I’m memorizing poems. By choice. It’s a road not taken by many, and though way has led on to way, I’ve been able to return to it thanks to the daring editors here at Tweetspeak Poetry.

In Moonwalking with Einstein: The Art and Science of Remembering Everything, Joshua Foer suggests that “To really learn a text, one had to memorize it.” And as the early-eighteenth-century Dutch poet Jan Luyken put it, “One book, printed in the Heart’s own wax / Is worth a thousand in the stacks.”

Is one poem memorized worth a thousand on my shelf? Could I possibly memorize a thousand poems? Probably not unless I channel Peter of Ravenna who, according to Foer, claimed to have memorized “twenty thousand legal points, a thousand texts by Ovid, two hundred of Cicero’s speeches and sayings, three hundred sayings of philosophers, seven thousand texts from Scripture, as well as a host of other classical works.”

When I started memorizing T.S. Eliot’s The Love Song J. Alfred Prufock, who could have known that path would bend into a vibrant wood trembling with poems of every color just waiting to impress themselves into my heart’s wax? My husband applauds my effort but is still not convinced of the value of memorizing anything (except maybe the multiplication table), especially now that Google has already filed it for ready access. Even so, one night he unexpectedly launched into a recitation of Frost’s The Road Not Taken. He insists he never intentionally took it to heart but loved the poem so much he just spent a lot of time with it. (He also knows Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening but claims he didn’t memorize it in school or elsewhere either. I’m not sure I totally believe him on either count.)

Foer says that “today it often seems we remember very little.” Thanks electronics. Thanks Google. Thanks speedy life. Without the infinite flow of information as close as our fingertips, we might find ourselves more able to commit to memory the poems we could call upon in those rare times when that information is much further away. And as happy as I am for having committed it to memory, I secretly hope I never find myself confined in some solitary space with only Prufrock to keep me company.

It might be good, though, to have some other friends. After my husband’s spontaneous recitation of Frost, I decided to spend some time with Robert Frost and The Road Not Taken. Memorizing it would, comparatively, feel like a leisurely walk in the woods. I was right. While it took me the length of a pregnancy to commit Prufrock to heart, it took all of two days for Frost.

The Road Not Taken

Two roads diverged in a yellow wood,

And sorry I could not travel both

And be one traveler, long I stood

And looked down one as far as I could

To where it bent in the undergrowth;

Then took the other, as just as fair,

And having perhaps the better claim,

Because it was grassy and wanted wear;

Though as for that the passing there

Had worn them really about the same,

And both that morning equally lay

In leaves no step had trodden black.

Oh, I kept the first for another day!

Yet knowing how way leads on to way,

I doubted if I should ever come back.

I shall be telling this with a sigh

Somewhere ages and ages hence:

Two roads diverged in a wood, and I—

I took the one less traveled by,

And that has made all the difference.

—Robert Frost

While “The Road Not Taken” is probably Frost’s most well-known poem, it is, as Glynn Young reminds, perhaps also his most misunderstood poem, initially written “as a kind of joke about [his friend Edward] Thomas’s indecision and a parody on the romantic imagination.”

When I read the poem again, my imagination transported me to a yellow wood, like places I’ve been many times in real life. The sun’s rays poured through empty branches, above leaves that now crunched underfoot in the crisp air. I thought about the roads I’ve chosen in my life and where they ultimately led. I felt joy and some regret, but mostly wonder, about where other roads might have taken me. I wanted to gather up some leaves and iron them between sheets of waxed paper to preserve them—like I wished I’d preserved so many things I’ve forgotten.

As for poems, I’m choosing to collect them now, and remember.

Read more on Sandra’s dare to Commit Poetry

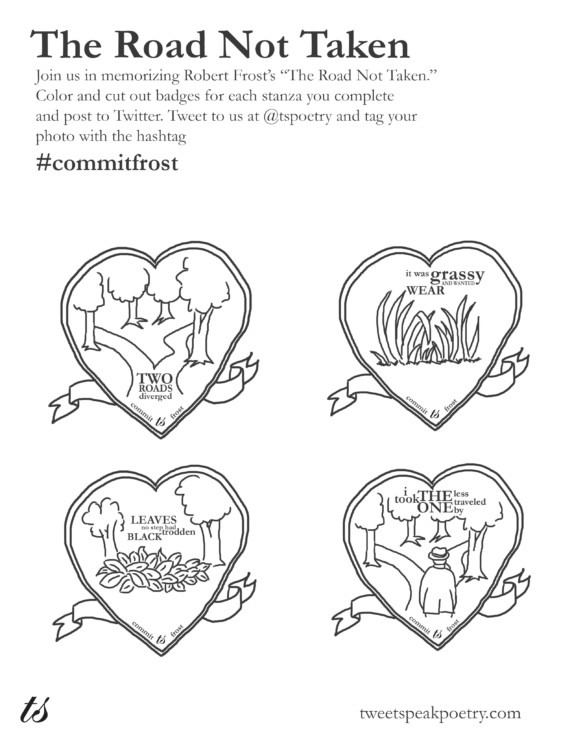

Get your own printable badges and memorize Robert Frost’s “The Road Not Taken” with Sandra.

Photo by geir tønnessen, Creative Commons license via Flickr. Post by Sandra Heska King.

- 50 States of Generosity: Iowa - April 7, 2025

- 50 States of Generosity: Montana - January 27, 2025

- 50 States of Generosity: Idaho - December 16, 2024

Megan Willome says

So glad you got the whole thing recited before getting struck by lightning. 🙂

I thought about you and this poem–the roads you have taken, the roads you are taking, those you will take. Michigan. South Florida. T.S. Eliot and Robert Frost. Thanks, Sandy.

Sandra Heska King says

We do get some pretty wild lightning! I just had this thought–there are a lot of bends and S-curves in South, T.S., and Frost. And the Michigan’s “g” keeps circling. 🙂

I’m glad you’re part of my journey.

Donna Falcone says

Oh Sandra, I just loved hearing you recite this poem! And that LW …. maybe it’s LMW, with a bit of Mischeif in the middle! LOL 😀

I don’t remember memorizing poetry in High School, but I suspect I probably did. I do remember memorizing a lot of music for our Madrigal and other performances, and a lot of lines for plays. I remember I loved ee cummings, and it was his lower case that really drew me in. I was so inspired by such a form-rule breaker! To me, he was just so cool. Ha ha. Yes, I was drawn to the wild ones.

Sandra Heska King says

Ha. Yes. LMW. That works.

I clicked on some slide show yesterday about “stuff you didn’t know about I Love Lucy,” and it said Desi Arnaz had a fantastic memory. That he could read through a script or something and boom have it down. I’m trying to verify that.

And e.e. cummings? I just discovered some of his love poems. I don’t remember learning about them in school.

Bethany R. says

Enjoyed watching your video, Sandra. And the closing of this post is poetic. Absolutely love this and the image of you wishing to iron leaves and preserve them. And then: “As for poems, I’m choosing to collect them now, and remember.”

Sandra Heska King says

Thanks, Bethany. I guess you could say I’m trying to press poems in the pages of my head and heart now. Maybe some pieces will crumble down the road and fall out. Then again… maybe not. I haven’t lost any Prufrock yet. 😉

Sharon A Gibbs says

What a beautiful job! I admire you for taking these challenges. I have memorized a few poems (mostly Neruda) this summer, but I am not sure I could publish them and appear as collected as you.