In a box stored in the basement of our home, I have a record of my school history, grades 1 through 12. It was a box my mother kept, and kept adding to, and included everything from report cards and penmanship books to tests and notebooks. Best of all, my mother put a date on everything.

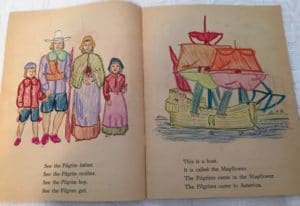

And so, from 1958, I find the “November Activity Unit,” about the size of a very thin comic book. We had one of these for each month of the school year, and the units contained topical information about the month, holidays, and similar events, with every page containing illustrations to color. I suspect this was a form of busy work, something to keep the children in my second-grade class occupied while the teacher did other things. By second grade, I was familiar with Thanksgiving dinner, but it was that activity unit that introduced me to the Pilgrims.

Not bad coloring for a second grader.

A few years later in sixth grade, we read The Courtship of Miles Standish by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, and that reading supplemented what we were learning in history. Longfellow took the names of his main characters in the poem—Miles Standish, John Alden, and Priscilla Mullins—from the names of real people who arrived in America on the Mayflower. The poem includes events that are certainly historical—conflict with native Americans and disease—but how much of the love story is factual is open to debate.

The narrative poem is the story of a love triangle. Captain Miles Standish leads the colony at Plymouth, and he’s certainly egocentric, interested in his own history, pedigree, and importance. His secretary is John Alden, who is almost the polar opposite of Standish. One day, Standish, himself a widower, decides he must remarry, and fixes his attention on the lovely Priscilla Mullins, who just happens to be John Alden’s love interest—of which Standish is naturally oblivious. Worse yet, Standish charges Alden with delivering his message verbally to Priscilla. Standish may be heroic (at least in his own eyes) in how he fights the hostile natives, but he’s tongue-tied and afraid of addressing Priscilla directly.

Alden does his duty for his commanding officer, if not to his own heart. He goes to Priscilla, and begins to praise the wonderful Miles Standish. Priscilla has some objections to both the content and the form of the lover’s suit, but Alden presses on. From Part 3, “The Lover’s Errand”:

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow in 1859. Photograph by Matthew Brady.

Still John Alden went on, unheeding the words of Priscilla,

Urging the suit of his friend, explaining, persuading, expanding;

Spoke of his courage and skill, and of all his battles in Flanders,

How with the people of God he had chosen to suffer affliction,

How, in return for his zeal, they had made him Captain of Plymouth;

He was a gentleman born, could trace his pedigree plainly

Back to Hugh Standish of Duxbury Hall, in Lancashire, England,

Who was the son of Ralph, and the grandson of Thurston

de Standish;

Heir unto vast estates, of which he was basely defrauded,

Still bore the family arms, and had for his crest a cock argent,

Combed and wattled gules, and all the rest of the blazon.

He was a man of honor, of noble and generous nature;

Though he was rough, he was kindly; she knew how during the winter

He had attended the sick, with a hand as gentle as woman’s;

Somewhat hasty and hot, he could not deny it, and headstrong,

Stern as a soldier might be, but hearty, and placable always,

Not to be laughed at and scorned, because he was little of stature;

For he was great of heart, magnanimous, courtly, courageous;

Any woman in Plymouth, nay, any woman in England,

Might be happy and proud to be called the wife of Miles Standish!

But as he warmed and glowed, in his simple and eloquent language,

Quite forgetful of self, and full of the praise of his rival,

Archly the maiden smiled, and, with eyes overrunning with laughter,

Said, in a tremulous voice, “Why don’t you speak for yourself, John?”

Priscilla Mullins is nobody’s fool, and she knows who’s really expressing his love.

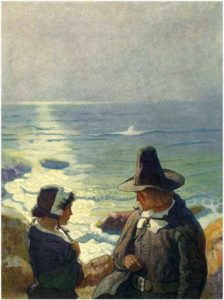

Priscilla Mullins and John Alden, as painted by N.C. Wyeth

What follows are reports of a native uprising, with Standish going off to wage battle. Alden, in despair but loyal to his captain, decides he must leave Plymouth on the return voyage of the Mayflower to England. The poem ultimately ends happily, and with a significant surprise.

The poem was first published in 1858, some 100 years before I colored those pictures of the Pilgrims. In some ways, it is a counterpoint to Nathaniel Hawthorne’s great novel, The Scarlet Letter, published in 1850 and a historical novel about the Puritans in the Massachusetts Bay Colony. We often combine, or confuse, the Pilgrims with the Puritans, but they were originally two different groups of colonists that settled near each other.

Hawthorne painted a rather unflattering picture of the Puritans, showing them intent on shaming Hester Prynne for her illegitimate child and for her pride. He breathed life into the definition of the word “puritanical” we know today. Longfellow painted a much different, and more positive, picture of the Pilgrims, and his poem remained popular well into the 20th century. (One might acknowledge the echoes of the differences between the two in our current national politics.) But the fact remains that both the novel and the poem are fiction and only broadly grounded in historical fact.

None of that would have necessarily mattered to a second-grader working hard on coloring his activity unit pages and trying desperately to keep within the lines. Or even to a sixth-grader, being taught colonial history and reading and studying a poem based on it. But those two exercises, four years apart, were common educational practices in mid-century America, and they helped shape how millions of us came to understand where the United States came from.

And The Courtship of Miles Standish is still a delight to read.

Related:

Our Best-Known Patriotic Poem: Longfellow Visits a Church

The Poem as Modern Myth: “Evangeline” by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

Photo by Joel Penner, Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post by Glynn Young, author of the novels Dancing Priest and A Light Shining, and Poetry at Work.

__________________________

“I require all our incoming poetry students—in the MFA I direct—to buy and read this book.”

—Jeanetta Calhoun Mish

- Longfellow’s “Paul Revere’s Ride”: Creating a National Legend - April 17, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Katie Kalisz and “Flu Season” - April 15, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Michelle Ortega and “When You Ask Me, Why Paris?” - April 10, 2025

Sandra Heska King says

That is some great coloring. I love that your mom kept all of that stuff. I have bins of my kids’ stuff that I need to sort through. I’m not sure how much of it they’ll actually want.

I loved pilgrim days at school. But for the life of me, I don’t remember this poem. I wonder if I just had a poetry block. I’ve got so much catching up to do.

Glynn says

Don’t forget to date the kids’ stuff! They will appreciate it.

I just finished reading Longfellow’s “Hiawatha.” It was nothing like I remembered it being, but it had been more than 50 years ago.

Sandra Heska King says

I think I remember dating most of it.

We have a couple different Classics Collections that I want to start working my way through. Longfellow is in there. Have you ever been to Tahquamenon Falls? It’s kind of awe-inspiring to read Hiawatha next to them.

Glynn says

No, I haven’t been there. But I will have to look into it.

Bethany says

Interesting note about the contrast between the Pilgrims in The Scarlett Letter, and those in The Courtship of Miles Standish. I would like to read the latter.

Katie says

My mother had a bottom drawer of her and my father’s dresser dedicated to our report cards, papers, drawings, etc. At a family reunion a few years ago, my siblings and I sat around mom’s dining room table going through our manila folders. What a fun time we enjoyed revisiting grade school pictures, projects and and even a few VBS crafts. I think the shared remembering brought us closer together.

Thank you for this meaningful post and links, Glynn:)