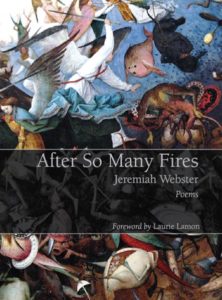

From the first poem in the collection After So Many Fires by Jeremiah Webster, you know you’ve entered a landscape different from so many contemporary collections. There is no irony, no cast of a jaundiced eye or air of boredom and disillusionment, no personal angst or confession.

Instead, in the poem “Credo,” we discover the immense discomfort of attempting to live a structured life in a world gone mad: “There is the torching: / novels, martyrs, torching / of twenty-one centuries as the world falls apart. / I study my books / as the world falls apart.”

It’s a sense of being a stranger in a strange land, of creating a life in a world that has seemed to have gone mad. It’s a madness that runs through our language, our technology, our culture—all of the things we construct to make sense of the world around us.

With simple language and images, Webster has constructed a collection that resonates over and over again. He juxtaposes nature and technology, mixes faith and hope with stories from the Associated Press, ponders how many whales had to die to provide the oil for the light by which Emily Dickinson wrote her poems, and considers how poets are the only ones who after death remain in their line of earthly work . And fish, and the symbol of fish, become part of the ritual in this brave new world.

Ritual

tons of icthyoid offspring

like the time I was in London

hearing vespers in a dead language

not knowing what it could mean

to fish or to sing anymore.

I abandon all expectation

as winter crows fly regardless

of food outside my window.

To wait without hope

is not the same as despair.

I wave on my way past the suicides,

listen to the hum of my voice mosey

off into the maples and by the stream,

where all manner of fish shimmer

to remain in their world.

Jeremiah Webster

Webster is an associate professor of English at Northwest University in Kirkland, Washington. He received his B.A. and M.I.T. degrees from Whitworth University, an M.F.A. degree from Eastern Washington University, and a Ph.D. from the University of Wisconsin. After So Many Fires is his first collection of poetry. He has also written introductions for collections by T.S. Eliot and William Butler Yeats.

Even with all the madness, Webster still finds hope in this world. After So Many Fires is ultimately a hopeful work, one that understands what light glimmers amid the madness.

Photo by Jon Bunting, Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post by Glynn Young, author of the novels Dancing Priest and A Light Shining, and Poetry at Work.

__________________________

“I require all our incoming poetry students—in the MFA I direct—to buy and read this book.”

—Jeanetta Calhoun Mish

- Poets and Poems: Forrest Gander and “Mojave Ghost” - March 27, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Siân Killingsworth and “Hiraeth” - March 25, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Donna Hilbert and “Gravity” - March 20, 2025

Laura Lynn Brown says

“[P]oets are the only ones who after death remain in their line of earthly work.” Hm. Interesting.

I think I need to read this one. Partly for the presence of fish.

Bethany R. says

That line stood out to me too, Laura.

Do you enjoy fish? 🙂

Jim Meals says

This is an excellent review. Jeremiah Webster’s poetry is refreshing because of the total lack of personal angst. Webster has no illusions about the world we live in and yet he remains an optimist. As a result, his poetry has tremendous vitality and more than a touch of humor.

Bethany R. says

I’m always looking for humor in my reading (and in life). Glad you pointed that out, Jim. And welcome to the Tweetspeak Poetry community.

Glynn says

I continue to learn that good poetry is being published, and not only by the large publishing houses. I really enjoyed this collection by Webster.

Megan Willome says

“To wait without hope

is not the same as despair.”

Really, really like those two lines.

Katie says

Glad you pointed out those lines, Megan – I had missed them entirely.

Much to ponder here. Has set me on another meander through Glynn’s posts and reviews:)