On April 5, 1860, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (1807-1882) climbed the stairs of the tower at Old North Church in Boston. The view had changed considerably in the 85 years since the start of the American Revolution—more and taller buildings, countryside and woods swallowed up by development, and certainly more people on the streets below and nearby.

But Longfellow thought back to April 18, 1775, and the tense and desperate times the colonials were living and shaping. And like any good poet, he considered those times, and his view from the church tower, and a poem began to form. He began writing it the very next day.

“Paul Revere’s Ride” in The Atlantic Monthly, January 1861

Paul Revere’s Ride was published in The Atlantic Monthly in January, 1861, and since then has passed into folklore and American legend. For more than a century after, American schoolchildren memorized the poem, individually and as a classroom exercise (I can testify to the reality of both individual memorization and classroom recitation, often in groups).

The poem is not historically accurate, as Longfellow well knew. There were actually three riders that night, spreading the alarm of the arrival of the British—Paul Revere, William Dawes, and Samuel Prescott. And it was Revere himself who hung the lanterns (“One if by land and two if by sea”) in the church tower, before he began his ride.

But Longfellow was more interested in narrative and myth. It made a better story if there was only one rider, that rugged American patriot exemplifying individual resolve, courage, and determination. It also made a better-flowing poem. It’s hard to imagine a poem entitled “The Midnight Ride of Paul Revere, William Dawes, and Samuel Prescott.”

The poem, like all poems, was written in a context, and that context was the nation preparing to tear itself apart. It was an election year, and the splitting of the vote would result in the election of Abraham Lincoln. But the United States had experienced a decade of rising tension, violence in “bleeding Kansas and Nebraska” and even in the halls of Congress itself, when Senator Charles Sumner, Longfellow’s good friend, had been beaten nearly to death with a cane by a congressman from South Carolina. And now, with the election, tensions were rising even more.

By the time the poem was published the following January, South Carolina had already seceded. The nation was being sundered, and Longfellow, staunchly anti-slavery, hoped the poem would prove a rallying cry for the country to do what was right and perhaps, by appealing to a common history, calm the political explosion. It didn’t. The explosion happened anyway, and more than 500,000 Americans would die.

The inn in Sudbury that was the model for Wayside Inn

In 1863, Longfellow wrapped the poem inside a new collection, Tales of a Wayside Inn. Seven friends sit around the fire at an inn in Sudbury, Massachusetts. To pass the time, they begin to tell each other stories or tales in poetic form. The seven are the landlord, a student, a young Sicilian, a Spanish Jew (Longfellow would not likely use that name or description today), a theologian, a poet, and a musician. The landlord kicks off the storytelling and recites “Paul Revere’s Ride.” The other friends follow with their own tales. Longfellow worried that people would think the collection was a rip-off of Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, but was counseled to go ahead. And while some drew a connection, the already familiar “Paul Revere’s Ride” mitigated the comparisons.

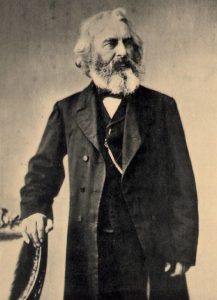

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

By the time Tales of a Wayside Inn was published, Longfellow also had a personal context for the poem. He was still grieving the loss of his wife in an accidental fire in 1861, and his son had been injured in a Civil War battle. A poem liked “Paul Revere’s Ride” spoke to the sense of national urgency, the mission to be accomplished, and the reason for terrible events like revolutions and civil wars.

The poem may not be memorized today as much as it once was, but it still very much alive. Recently, radio show host and author Eric Metaxas challenged schoolchildren with a contest, to film themselves reciting the poem. What resulted is something wonderful.

Perfectly accurate from a historical perspective? No. The kind of poem that might be written today and published in The Atlantic Monthly? Not likely. But “Paul Revere’s Ride” is still our best-known patriotic poem, and it still speaks of unity, common heritage, and common purpose in a divisive time.

Related:

The ebook version of Tales of a Wayside Inn are free from Amazon Kindle, Barnes & Noble Nook, and Project Gutenberg

Photo by Dong Ji, Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post by Glynn Young, author of the novels Dancing Priest and A Light Shining, and Poetry at Work.

__________________________

“I require all our incoming poetry students—in the MFA I direct—to buy and read this book.”

—Jeanetta Calhoun Mish

- Poets and Poems: Forrest Gander and “Mojave Ghost” - March 27, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Siân Killingsworth and “Hiraeth” - March 25, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Donna Hilbert and “Gravity” - March 20, 2025

Bethany R. says

“‘Paul Revere’s Ride’ is still our best-known patriotic poem, and it still speaks of unity, common heritage, and common purpose in a divisive time.”

Thank you for this post. My daughter and I enjoyed watching the kids recite the poem. Happy Independence Day!

Megan Willome says

That video is excellent!

Katie says

I so agree, Megan!

Yay for Eric Metaxas contest and all those that participated.

SandraHeskaKing says

This video puts my measly efforts to shame. This poem is on my list to memorize–but never to be recited as well as those kids.