Christopher Tolkien, the youngest of J.R.R. Tolkien’s three sons, will be 93 this year. He is his father’s literary executor, and he has spent the years since his father’s death in 1973 poring over papers and files; considering an array of various texts, different versions of stories and poems; staying true to his father’s vision; and helping publish a considerable number of books that represent both wonderful stories and insights into The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings. It is because of Christopher that we have The Silmarillion, The Children of Hurin, many of the lost tales, the elder Tolkien’s translation of Beowulf, and many other works.

J.R.R. Tolkien

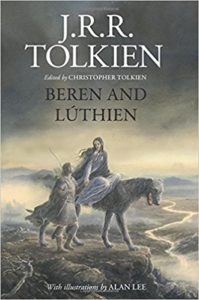

The latest, and possibly the last, is Beren and Luthien, a love story between Beren, a mortal man in exile after his father and clan are killed, and Luthien, an elf princess (the idea of which was carried over into The Lord of the Rings). Luthien is also called Tinuviel by Beren, and it is by that name we see her part in the story. Beren sees Luthien dancing in the woods and falls in love with her. Her father isn’t exactly pleased, and he agrees to the marriage only if Beren can steal a Silmaril, a jewel in the crown of Melkor, the Black Enemy, also known as Morgoth—and a forerunner of Sauron in the trilogy. He’s captured and enslaved in the kitchen, and Luthien travels to his rescue. With the help of a giant dog (who tricks an evil cat), she succeeds in freeing Beren, and then more adventures happen.

Tolkien wrote Beren and Luthien when he returned to England to recover from illness after the Battle of the Somme in World War I, the longest battle (July 1 to November 18, 1916) and the bloodiest battle of the war (one million men killed or wounded). The story was written and rewritten many times, in prose and verse forms. Numerous ideas found their way into his other works, and especially the trilogy and The Hobbit.

What Christopher Tolkien has done with this publication is something special. He includes the original story, and he also includes various prose and verse sections that his father worked on over a period of some 14 years. This is an insider’s view of the working of a story by one of the most creative minds of the 20th century.

Here is a section from one of the verse amplifications of the story, which explains the beginning of Beren’s exile.

his sword and bow, and sped like wind

that cuts with knives the branches thinned

of autumn trees. At last he came,

his heart afire with burning flame,

where Barahir his father lay;

he came too late. At dawn of day

he found the homes of hunted men,

a wooded island in the fen

and birds rose up in sudden cloud—

no fen-fowl were they crying loud.

The raven and the carrion-crow

sat in the alders all a-row;

one croaked: ‘Ha! Beren comes too late,’

and answered all: ‘Too late! Too late!’

Then Beren buried his father’s bones,

and piled a heap of boulder-stones,

and cursed the name of Morgoth thrice,

but wept not, for his heart was ice.

Edith Tolkien’s tombstone

The prose and the verses are the stuff of myth and legend, of stories told and passed down through the generations. They are full of heroism and courage in the face of insurmountable odds, of heroes using trickery when necessary, of love winning in the end even when it loses. Tolkien had the names “Luthien” and “Beren” inscribed on the tombstone for his wife Edith and himself, which suggests some of the deep personal connections he felt to the story he had written.

The volume includes wonderful illustrations by Alan Lee, who has illustrated a number of Tolkien publications.

In a sense, the writings we know as Tolkien’s began with Beren and Luthien, and it takes its place in the grand mythology of the First Age and Middle Earth that Tolkien devoted so much of his life to. It is fitting that this first story may also be the last to be published.

Related:

“The Children of Hurin” and “The Lay of Aotrou & Itroun” by J.R. R. Tolkien

Poets and Poems: J.R. R. Tolkien and “Beowulf”

Poetry Date: Sisters Read Tolkien and One Wears Dagger

Photo by Michael Theis, Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post by Glynn Young, author of the novels Dancing Priest and A Light Shining, and Poetry at Work.

__________________________

“I require all our incoming poetry students—in the MFA I direct—to buy and read this book.”

—Jeanetta Calhoun Mish

- Longfellow’s “Paul Revere’s Ride”: Creating a National Legend - April 17, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Katie Kalisz and “Flu Season” - April 15, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Michelle Ortega and “When You Ask Me, Why Paris?” - April 10, 2025

Megan Willome says

That excerpt reads so well aloud.

Thanks, Glynn!

Bethany R. says

I did not know about the gravestone inscriptions—fascinating. This sounds like a rich book and pairing it with Alan Lee’s artistry puts it over the top for me (he’s my favorite illustrator of Middle Earth).

I remember Aragorn (“Strider”) singing about Luthien and Beren in The Lord of the Rings. Looking online, I see that both Aragorn and Arwen were descendants of them.

Tolkein went to great lengths to give multilayered backstories—not to mention whole languages—to his characters. He makes his stories feel like they’re rooted in our real history, and in way they now are.

Donna Falcone says

That poem is really something special. I loved reading it. I also found it so interesting about the tombstone inscriptions – of course. It makes perfect sense – such a deep connection between the one who writes and the characters he creates. Thank you Glynn!

Prasanta says

My 16 year-old son requested this very book from the library when it was released, and he just finished it! He felt inspired to write a story of his own after reading. It’s wonderful to see how Tolkien incorporated verse into his tale.