This is not a story about a nice man. This is a story about a greedy, scruffy, fearless pirate named Boris von der Borch. This is Tough Boris.

Pre-Reading

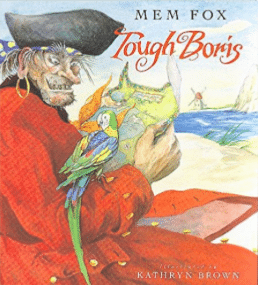

“The story is simple,” I tell my students. “There aren’t a lot of words on the pages, so you’ll want to look carefully at the pictures.” I hold up the cover with Boris on it and say, “That is, if you can.” Boris is not an easy guy to look at.

The kids lean back, disgusted.

“He’s scary!”

“He’s mean!”

I look at the cover, and say, “How can you tell?”

“His eyes!”

“His smile!”

His eyes do have a crazy look to them, and his smile suggests he’s up to no good.

“What is Boris?” I ask.

All at once, they tell me Boris is a pirate. They point out that they can tell because he’s wearing a pirate’s hat, a red pirate’s coat with brass buttons, there’s a parrot on his shoulder, and he’s holding a map.

“Good job,” I tell them. “That’s what I mean when I say look at the pictures.”

It’s not easy to look at a man like Boris, and want to spend time on the kind of person he is. I almost feel guilty introducing these 5 and 6 year olds to him.

Almost.

I turn the page and point to a little boy sitting on a cliff with a case next to him. He can see Boris’ pirate ship.

“You’re going to want to watch for this little boy, and you’re going to want to watch for this case of his.”

“What is that case?” one student asks.

“It’s a snowboard!” another offers.

“It’s not a snowboard, but you’ll find out soon. Just keep an eye on it, OK? When you see the boy, put your thumb next to your heart.”

And so we begin.

The Interactive Read-Aloud

We learn that Boris is tough and massive, scruffy and greedy. Every page reveals a different part of this bad guy, and my students figure out what these words mean by looking at the pictures, and watching Boris in malevolent action.

It doesn’t take long for us to understand that Boris is a maniac, and while the kids look at the book cautiously, and with wide eyes, they also see a little boy: little fists with upturned thumbs shoot to hearts because the little boy made his way onto the ship. He is following Boris’ every move.

“There he is! There’s the little boy!” the students whisper excitedly. They whisper because they don’t want Boris to see this little boy. They are fully immersed in this story.

The little boy has come on the boat because Boris stole his violin. That’s what was in the case on the first page. At one point, Boris holds the violin he’s just snatched in one hand, clearly intrigued and clearly clueless as to what this thing is. Boris might be a vile human being, but he knows what he has is something special, even if he doesn’t know what it does.

So it goes with treasure whose purpose is disguised—can we look at it long enough to see what might glimmer?

One night, Boris takes the violin down to his room, and looks at it. On the next page, the violin is flying out the window, and the students scream, “The little boy! The little boy! He took back his violin!”

Indeed, he did, and that’s when the narrator tells us that Boris is scary. Swords are drawn, the hunt begins, Boris holds a finger simulating a slice of a throat, and the little boy hides.

He runs to a room at the bottom of the ship and begins to play his violin.

“All pirates are scary,” the next page says, and the little boy is now playing his violin surrounded by Boris and his equally disturbing crewmates. Here is where the pictures shift from the story. These pirates are scary, no doubt, but it is not all they are.

“What are they doing?” I ask.

“They’re listening.”

“Is listening scary?” I ask.

“No.”

“Have you ever been terrified to listen?”

They giggle and shake their heads, so I ham it up more. “I mean, have you ever screamed, “I don’t want to go to school today because I’LL HAVE TO LISTEN AND I’M AFRAID OF LISTENING!”

“NO!” their little bodies are wiggling, bubbling with smiles and laughter.

We study the two-page spread some more. The little boy plays his violin in a patch of light from a lantern. The light shines on the boy, and it spills onto the pirates. It creeps to their feet, and shins, like the swells and the tide that can carry their ship to who knows where if they don’t control it.

My students and I look closer. We notice that, even though many of the pirates are holding swords and daggers, the weapons are pointing down, not overhead ready for attack. Boris is actually using his sword to lean on. All of the pirates look mesmerized and soothed by whatever melody the boy is playing.

“Boris still looks scary,” one little boy says, “but he is small scary.”

“Yes,” I say, “there’s something else happening here.” I put the book on my lap and ask, “Has music ever done that to you? You could be in a really bad mood and then your favorite song comes on, and something changes?” I move my body like I’m dancing to a strong beat, and the kids giggle. Some clap along.

“I mean,” I stop, putting my hands up, “you can still remember why you’re angry or sad or afraid. That’s still there, but it’s not all that’s there.”

Music, like water and light has a power all its own—and on this page, though we cannot hear its sound, we cannot see the water, and we do not know how far the light will shine, we see the work they’re doing, revealing ever so slightly what we never imagined could be.

“Shall we keep reading?” I ask.

“Yes!”

The next page is another two-page spread, this time, almost all water. Greens and blues and black mix to form something deep and choppy. Boris’ ship is smaller, off to the side and the words, an unfinished sentence, are at the top in the sky. “But when his parrot died,”

“Oh, no,” the kids murmured.

“What happened to Boris’ parrot?”

“Why did the parrot die?”

I cannot answer these questions just as I cannot explain why we all feel terribly sorry for Boris; a man who is so scary it’s difficult to look at him.

The next page is wordless, but perhaps the most powerful. The little boy steps into Boris’ bedroom and finds him slouched in a chair, his back to us. The parrot lies on Boris’ lap, its bright green feathers hanging over his leg.

“How is Boris feeling?” I ask.

“Sad,” they all respond.

“How can you tell?” I prod. “There aren’t any words on the page. We can’t even see his face.”

“He’s not wearing his pirate jacket,” one boy says. Indeed, it is hung neatly, just underneath the empty birdcage.

“He’s holding onto his parrot,” another girl says, reaching towards the page, her index finger pointing to what was once alive.

They are observing sadness, just as they observed evil – with curiosity, care, and empathy.

“Can bad guys feel sad?” I ask in a baffled tone, as though this couldn’t possibly be.

“Yes,” they tell me.

On the next page, the little boy and Boris stand together, both of their faces so filled with sorrow it is perhaps more agonizing to look at then when Boris was planning his next hit. I point to the violin case the little boy offers to Boris so he can bury his parrot.

“Remember I told you to keep an eye on the case,” I remind students. “What kind of case is this?”

They see it’s a violin case, and they see that the boy is passing on something he used to protect what he loves, to Boris, so Boris can bury his own treasure. The case and the parrot slip into the sea, carried off by the water, while Boris cries and cries.

Try a Post-Reading Activity

I found this story in a cardboard box hidden in a closet in the library. I’d been cleaning it out, thinking about setting up a workspace for myself. I’ve been doing the organizing slowly, hesitantly, because I don’t know if they schools I serve in will have me back. I’ve never worked in a school library before, and though I’d like to set up a little place to collect and work out ideas, a place to call my own, I’m afraid someone might say, “No, no. That’s not yours. You don’t belong here.” But like Boris when he first saw that violin, I held on to Mem Fox’s story because I knew it was special – I just wasn’t sure what it could do – or what I could do with it.

The closet I was in is dark, but the light from the library outside was enough for me to read about Boris and what he was capable of. I fell in love with that pirate and I realized I had to share him with the kids I see. Treasure cannot be protected.

When we finish reading, I hold up a rolled up piece of paper tied with yarn. “I thought we could make our own treasure maps.” I unroll the paper, revealing a treasure chest and four islands.

I hand each child her own map and tell the students that they are to put their names on the chest. “Because you are all treasures,” I say.

The chest is open, showing instead of coins, words like shy, wild, scruffy and sad. I tell the students these are all words that make up who we are. “We’re not all of these things, but we understand them, don’t we? We feel them— sometimes more than one —at times, don’t we?”

I point to the islands and I say they are to give each island a name that represents who they are. Some choose to sound out words they have trouble spelling. Some color what they think sad might look like. There are family islands, wild islands, sports islands, and several students draw “parrot islands,” in honor of Boris’ buddy.

“I don’t want to forget,” a little boy tells me tapping on his parrot island. It is green like the feathers that cascaded down Boris’ lap as he held his friend.

I don’t know if he means he doesn’t want to forget the parrot, or Boris, or the story itself, but I don’t ask. I just say, “I don’t want to forget, either.”

We’ve found treasure, and I want us to hold it long enough to see what it can do.

Photo by Ary Chst, Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post by Callie Feyen.

- Poetry Prompt: Courage to Follow - July 24, 2023

- Poetry Prompt: Being a Pilgrim and a Martha Stewart Homemaker - July 10, 2023

- Poetry Prompt: Monarch Butterfly’s Wildflower - June 19, 2023

Megan Willome says

I love every part of this. Thank you, Callie!

Callie Feyen says

Thank you for reading, Megan! This one was good for me to write. I’m glad to know you liked it.

Bethany Rohde says

I second that, Megan. Beginning to end, a colorful, heart-felt, engaging piece. I like the way you keep the kids involved with suggestions like putting a thumb on their heart when they see the boy. Smart. Fun.

(I was enjoying this whole scene so much that I looked at your website and saw you’ve created elementary-age reading journal! 🙂 Had to buy it for my daughter—it will be such a fun end-of-the-school-year surprise. (She loves workbooks, this looks even funner!))

Callie Feyen says

Thank you, Bethany. This book was one of my favorites I read this year. I think I read it to 10 classes and each group was stunned by Boris, and they loved that little boy.

And thank you for purchasing a journal! Those were such fun to make. I hope your daughter likes it! 🙂

L.L. Barkat says

I do believe these children will always remember you. And I hope they remember that someone thought they were a treasure.

I’m guessing that’s not what most kids would come away with, from an ordinary reading of Tough Boris. But then, you don’t do ordinary readings. 🙂

Callie Feyen says

You help make it so that I don’t settle on doing ordinary readings. You help me push past what is ordinary and see what else I can show the world.

Lexanne Leonard says

“Tough Boris” is one of my students’ favorite read alouds. They love to participate in echoing back the description of the pirates. And they all have something to share when we talk about losing a loved one. It’s wonderful to know that read alouds still have a place in other classrooms.

A few years ago we were told that this way of interactive reading should only take five minutes out of our day and then move on to the more important activities.

Of course, I would have none of that. Moving on so quickly will never happen in my classroom – a classroom whose teacher comes from an acting background and knows instinctively how bringing stories alive does more than just entertain students.

Keep up the good work. Our voices need to be heard strong and clear. This is one vital arm in a vibrant literate classroom.

L.L. Barkat says

And we wonder why comprehension is a problem for so many kids? Ai.

Go, you. Keep the love in. 🙂

Donna says

I’m glad you’d have none of that so that your students could have so so so much more!

Callie Feyen says

You know, once people start giving rules to how one ought to read a book, or what one ought to take away from reading a book, or, well, you get the idea, my stomach starts to get upset. I’m glad you “would have none of that.” It would be fun to visit your classroom someday.

Donna says

Callie, this is a beautiful piece…. of love to have been a fly on the wall,… or violin case!