“I am sorry,” she said.

“I did love to fly,” was all he could reply.

— Jackie Morris, The Wild Swans

I feel for her, really.

I mean, what’s a poor princess to do?

Her father has stashed her in a castle so well hidden that even he cannot find it without an enchanted ball of twine (easily stolen by a distrusting wife, it seems). Her brothers have turned into swans and flown south. And a witch (who looks suspiciously like a distrusting wife) has made the girl unrecognizable.

I get why she did what she did. When Morgana, Queen of the Fae Folk, gives you the opportunity to rescue your swan-prince brothers from their feathered captivity and bring them back from on-again, off-again manhood — and warns you that if you utter a single word before you complete your impossible tasks they will all die, every last one — it’s not as though you can very well call an impromptu focus group to get feedback on your plan. No, there in your sleep, you just decide to go out and do it. You’ll get the stinging nettles and stomp on them and spin thread to make shirts like you’ve been told, damn your better judgement and the bloody blisters on the soles of your feet to hell.

There are those, of course, who will readily empathize with Eliza’s plight moreso than that of her brothers. (It’s much easier to imagine being the person given the implausible mission than muddle through the complex emotions that come with being a swan one minute and a boy the next, after all.) And she makes a very sympathetic figure, all in all. Day in and day out, she tirelessly subjects her body to brutalizing pain. She allows herself to be abducted by a prince, albeit a kind one who genuinely cares for her. She is wrongly accused by a scorned and vindictive bishop, imprisoned and sentenced to death on the pyre (a funny little contraption that rhymes, conveniently enough, with fire), all the while silently crafting the garments that are supposed to rescue her brothers — if only they can be found before she dies — even as she is being hauled out to the town square to be killed, all without uttering a single, solitary word. By all appearances, she has sacrificed everything to break the curse under which the young men languish.

In our concern for Eliza, it is easy to miss the one thing she does not give up and it is here that Jackie Morris creates a powerful pivot in her retelling of The Wild Swans tale: she has not given up the idea that she knows what her brothers want and need. She holds close the idea that they are suffering in their dual lives, that they find their swan lives something of a misery.

She does wonder, however briefly, though: “Even as she slipped into troubled sleep, she wondered if Cygfa would thank her.”

We don’t learn much about the other brothers, but we know that the youngest, Cygfa, loves to fly. And he tells Eliza as much. “Sometimes, in the evenings, as a boy again, he tried to tell her that the only time he felt truly free, truly happy, was when he was riding the wind on white swan wings.”

It’s certainly not that Eliza couldn’t relate to such a predicament. She, too, had been on the receiving end of someone else deciding what she wanted, what was best for her. When the prince found her in the forest, “he only saw what he wanted to see, a proud, fierce young beggar woman. In his head he found the words for her, the words he wished to hear.”

None of this would stop Eliza from doing what she felt she must do, from seeing through her mission from Morgana, though even as her brothers swoop in at the last minute to complete their own rescue and snatch her from the flames, the gravity of her decision becomes clear:

One by one Eliza threw the nettle shirts over their white bodies until where there had been swans there now stood princes, tall, handsome princes, until the last swan, the burned swan, Cygfa. He backed away from his sister, shaking his head, all the time shaking his head.

Too late she remembered his love of flying, so caught in this moment that had been her hope and dream for so long. Too late. The last shirt fell over him, molded itself around the blackened feathers, healed the burns and clung to his skin until he stood tall, most beautiful of all, but ragged from the flames and with one wing where his arm should be, as one shirt remained unfinished.

Cygfa, who “would rather, given a choice, be a bird than a prince,” is now both and neither, left permanently straddling the line between man and swan with his one charred swan-prince wing poised in stark contrast to his man-prince body. Still he manages to offer comfort to his sister while simultaneously asserting his loss and his hope:

“I am what I am,” he said. “I have loved to fly. I will fly again.”

* * *

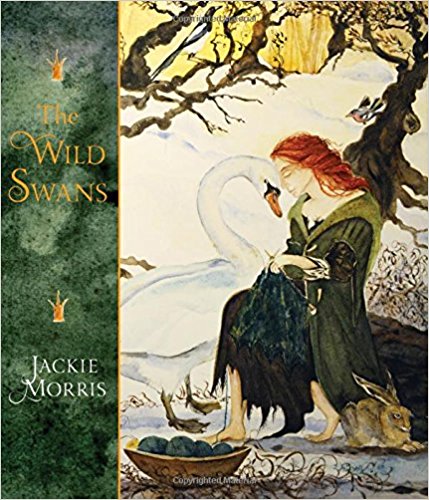

This month, we’re exploring a fairy tale theme, with our group Poetry Dare to commit The Stolen Child by W. B. Yeats to memory and our two-week book club discussion of The Wild Swans, by Jackie Morris. We invite you to share your thoughts on the story (perhaps you love the original) or on the twists and deeper explorations in Jackie Morris’ retelling. And since it’s National Poetry Month, we also invite you to share poems from the story — a poem inspired by the story or a character, a poem written to the fairy tale, or a found poem you’ve gathered from the book’s lyrical prose. Join us back here next week for more poems and thoughts about the tale. Here are a couple of poems to get you started:

Cygfa

If you had but asked

of dreams

of desire

a black-charred

white wing

would answer:

The unbreaking

of a curse.

Ritual

They call it a flight of passage, a boy

pulled airborne into some feathery vortex

driven south — further south, always south —

soaring by day under great white wings

that cloak the sun, and by night

to sleep as only a man,

to dream again of flying,

of a day that comes without promise

of night, of a seamless life

in one-winged body of proof.

Photo by Peter Ealey, Creative Commons via Flickr. Post and poems by Will Willingham, author of Adjustments: a novel.

__________________________

Adjustments is more than a good novel; it is a fine novel. It is, simultaneously, moving and real and surprising and true. We see ourselves and our personal histories in Will Phillips, Joe Murphy, and Pearl Jenkins. Like Will, we bear scars. In Joe, Pearl, and Cameron, we experience offered hope. This is a story about what matters, and it’s told beautifully well.

—Glynn Young, author of the Dancing Priest series.

- Poems to Listen By: Yondering—7: When You Came Back - April 16, 2025

- Earth Song Poem Featured on The Slowdown!—Birds in Home Depot - February 7, 2023

- The Rapping in the Attic—Happy Holidays Fun Video! - December 21, 2022

L.L. Barkat says

This was such a moving retelling of the fairy tale. I like how Cygfa’s story comes forward. This, this is heartbreaking:

“He backed away from his sister, shaking his head, all the time shaking his head.”

Especially after she herself knows what it is to be silenced and misunderstood… that she still does not see her brother for who he is and wants to be is tragic.

Oh, and why didn’t I see this before typing his name? Cygfa. From the beginning he contained what he “became”: a cygnet swan.

Will Willingham says

I had not noticed that either, and thought his name was so curious.

Well then. 🙂

Bethany R. says

I requested a copy of The Wild Swans from my library last week, and enjoyed reading it for the first time. I’m noticing now that it was the Hans Christian Andersen version. 🙂 But it’s interesting to consider the variations you mention here, and your thoughtful take on them. And my goodness—those poems: heartbreaking, beautiful.

L.L. Barkat says

Oh, this is a very different telling by Jackie Morris. Whole new story lines introduced. A must-read! 🙂

Will Willinghamt says

Bethany, if you ever do get the chance to read Morris’ version, it’s really wonderful. But all the better after having read the original story, so I’m glad you got that one too. 🙂 The story has so many things going on. 🙂