It was a packed house at the Southbank Centre Royal Festival Hall in London on Jan. 16. Ten poets were reading from their works, all nominated for the most prestigious award in British poetry—the T.S Eliot Foundation’s T.S. Eliot Prize. The prize is also monetary—20,000 pounds (about $26,000 at current exchange rates). Each of the 10 shortlisted nominees received 1,500 pounds (about $1,900).

Bernard O’Donoghue was there, reading from The Seasons of Cullen Church. Vahni Capildeo read from Measures of Expatriation (reviewed here at Tweetspeak Poetry last November; it won the Forward Prize). With the other eight, they represent some of the British poets writing today.

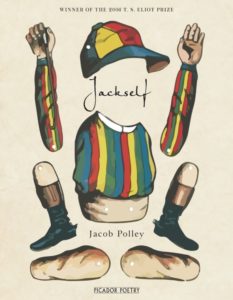

The winner was Jackself by Cumbrian poet Jacob Polley.

Jacob Polley

Polley, 41, teaches at Newcastle University. He’s the author of three previous poetry collections: The Brink (2003); Little Gods (2006); and The Havocs (2012). Both The Brink and The Havocs were shortlisted for the T.S. Eliot Prize. Polley has also published a coming-of-age murder mystery, Talk of the Town, which won the Somerset Maugham Award.

The prize judges called Jackself a “firecracker of a book,” and it is certainly that. It is a work centered in Polley’s birthplace of Cumbria in northwestern England, which encompasses the Lake District and was also the home of English poet Norman Nicholson.

But where Nicholson explored the landscape and the environment, Polley explores the folklore of the region, along with the poems many of us learned in childhood that originated in the area or nearby.

Cumbria is an area rich in tradition and history. The western end of Hadrian’s Wall terminates there; it was the heart of the fabled medieval kingdom of Rheged; it felt the impact of English-Scottish wars for centuries; and the Lake District was home to such writers as Beatrix Potter and William Wordsworth.

In the poetry collection, Polley creates two children on the verge of growing up—Jackself and his friend (and partner in mischief) Jeremy Wren. The two ramble through a childhood of folk tales and landscape, and in a sense become the folk tales and stories of childhood—Jack Frost, Jack Sprat, Jack O’Lantern, the house that Jack built, and Jack O’Bedlam. They are both characters and poem titles. But they stand for something else, something beyond folk tales and stories; they stand for the age of childhood itself.

An Age

today, like a tool in a toolbox,

to try to just be

high in the lovely lofts

of Lamanby

he stands at a cracked

window watching the gulls

flash and snap, like washing on a line

in the pale heat

the wormy heartwood floorboards

swell and creak

he stands for an age

not for a dark age,

not for an ice age or an iron age, but for a

pollen age, when bees

browsed the workshops

of wildflowers for powder

of light, and the cables

of a spider’s web were dusted with gold

by the unreceptacled breeze

Jackself doesn’t stand for “an ice age or an iron age, but for a / pollen age.” He’s describing childhood (I love that phrase “a pollen age”) and the lines that flow from childhood, dusting that spider’s web with gold. It’s beautiful imagery.

All 34 poems of Jackself have this kind of vivid imagining and combined playfulness and seriousness. It’s this creativity that the Eliot Prize judges recognized.

Related: An audio recording of Jacob Polley reading from Jackself at the T.S. Eliot Prize awards presentation.

Photo by Phillippe Put, Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post by Glynn Young, author of the novels Dancing Priest and A Light Shining, and Poetry at Work.

__________________________

“I require all our incoming poetry students—in the MFA I direct—to buy and read this book.”

—Jeanetta Calhoun Mish

- Longfellow’s “Paul Revere’s Ride”: Creating a National Legend - April 17, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Katie Kalisz and “Flu Season” - April 15, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Michelle Ortega and “When You Ask Me, Why Paris?” - April 10, 2025

Rick Maxson says

What a beautiful book, Glynn. I remember The House That Jack Built, one of the first poems I memorized as a child. It was featured in Collier’s Junior Classics with illustrations of each verse. Maybe Jack Sprat is in there somewhere and Jack be nimble.

Glynn says

Richard, “Jackself” is overflowing with Jacks, including some I never heard of.

Bethany Rohde says

Glad you shared the geographic connection between Jacob Polley and Norman Nicholson. It caused me to look up pictures of the Lake District (sigh), and go back and read Nicholson’s gorgeous featured poem again.

I was touched by the innocence, playfulness and realism in “An Age.” I paused after I finished reading it—wanted to “just be.”

Sandra Heska King says

This is beautiful. I love those first lines:

“Jackself is staying in

today, like a tool in a toolbox,

to try to just be”

and the pollen age, of course.

I love how you introduce us to all these poets we might never otherwise get to know.

Glynn says

Thanks for the comment, Sandra!