If a person were not paying attention, it might be easy to get the idea that Juan Gelman doesn’t think much of poetry, or of the power of words.

Were this truly the case, Gelman would be in good company. Many a rousing speech, good argument or solid critique has been written off by a detractor as “all talk” or “just words.” His body of work itself itself would seem to belie such a notion — the exiled Argentine poet with more than 20 collections of poetry to his credit, a number of prose works, and a long career as a journalist is the recipient of the prestigious Cervantes Prize and the Argentine National Poetry Prize. And yet, the expressions in some of his poems suggest that he might have come to the work with at least some reluctance.

The Art of Poetry

Of all trades, I’ve chosen one that isn’t mine.

Like a hard taskmaster,

it makes me work day and night,

in pain, in love,

out in the rain, in dark times,

when tenderness or the soul opens its arms,

when illness weighs down my hands.

The grief of others, tears,

handkerchiefs raised in greeting,

promises in the middle of autumn or fire,

kisses of reunion or goodbye,

everything makes me work with words, with blood.

I’ve never been the owner of my ashes, my poems,

obscure faces write my verses like bullets firing at death.

— Juan Gelman

The reluctance that seems to find voice ironically enough in a poem like “The Art of Poetry” comes, perhaps, from the nature of poetry itself, at least in those times when it can rise above the sentimentality of a Hallmark card (as Gelman’s undeniably does). Poetry is something he equates with work, and not only with work itself but also with the “hard taskmaster” driving him to it. And words, beyond “all talk, ” become as vital and alive as blood.

Gelman writes in blood, questioning the effectiveness of words, even as he weaponizes them:

Facts

While the current dictator or bureaucrat was speaking

in defense of the regime’s legally established disorder

he took a line or verse born of the cross

between a stone and a bright glow in autumn

outside the class struggle raged on / brutal

capitalism / back-breaking work / stupidity /

repression / death / police sirens splitting

the night / he took the line of poetry and

deftly opened it in half packing

more beauty into one part and then more

into the other / he closed up the line / put

his finger on its first word / squeezed

it aiming at the dictator or bureaucrat

the line shot out / the speech went on / the

class struggle went on / brutal

capitalism / back-breaking work / stupidity / repression / death /

police sirens splitting the night

this explains why so far no line of poetry has overthrown

any dictator or bureaucrat not even

a small dictator or bureaucrat / and also explains

how a verse can be born from the cross between a stone and a bright

glow in autumn or

a cross between the rain and a ship and also from

other crossings no one would know how to predict / in other words

births / marriages / the

shots fired by neverending beauty

— Juan Gelman

In the introduction to the collection Unthinkable Tenderness, translator Joan Lindgren says that Gelman saw “the need for a collision between language and reality.” Here, in the midst of lamenting the shortcomings of poetry — the most eloquent “line shot out” may not ever topple repression and death — he illuminates that collision, shining a light on poetry’s deep power in its “neverending beauty.”

Gelman surely understood poetry’s power, the potency of “just words” to effect change if even in a subtle revolution of our perceptions. Lindgren goes on in her introduction to Unthinkable Tenderness to note that Gelman’s work was one component of a linguistic study aiming to “locate in the function of language itself the capacity — or incapacity — to deny the humanity of ‘the other.'” It is this work of Gelman’s that I think becomes so important — the use of words to unearth and elevate our shared humanity.

In his short verse “The Word, ” Gelman finds poetry’s power in naming, recognizing the power of words to give (or take away) shape.

The Word

To Rigas Kappatos

The word that would name you rests in the shadows. When it

names you, you will become a shadow. You’ll crackle in the

mouth that lost you to have you.

—Juan Gelman

Lindgren recalled the study cited in Ordinary Men of what it took to compel German police in the early days of Hitler’s regime to kill Jews: “Difficulty was encountered only if the Jew spoke German, ” observing the importance of Gelman’s grasp of the “human connection of language and intimacy.”

If we keep reading we find that Gelman does accept his assignment from the “hard taskmaster, ” goes on to commit what Eduardo Galeano calls “the crime of marrying justice to beauty.” But he refuses to do so without an acknowledgement that while she might be a lady, poetry is not for the faint of heart; that those “just words” are sweaty and calloused from “hammering verbs together”; and that the poem becomes an embodiment of the soul of a movement, words themselves the worker who cannot be carried off.

Time Schedules

august went off arm in arm with the hydrangeas

and poetry has now settled down to work

regardless of the hot sunday

stretched out over the houses / quietly

transparent in her backdrop of light one she-bird doesn’t sing / one

tree doesn’t grow at the root of its silence / and

yet poetry

has seen august arm in arm with the hydrangeas and

has settled down to work breaking

the siesta’s contracts / ah lady who knows

why they picture you as someone peaceful when you may be

wearing leather aprons / must be sweating / must have

callouses from hammering verbs together or

driving off hatreds betrayals saving

the heart’s clarity / lady

seen in the thick of the fight

caring for the combatant / his childhood

surrounded by gunpowder or casualties / worker

the enemy cannot carry off / surrogate

for these embraces / these lives

—Juan Gelman

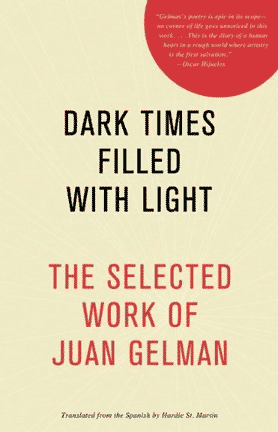

Dark Times Filled with Light Book Club Announcement post

Dark Times Filled with Light: Things They Don’t Know

Photo by Agustín Ruiz, Creative Commons via Flickr. Poems by Juan Gelman, translated by Hardie St. Martin, reprinted with permission of the publisher. Post by LW Lindquist.

- Earth Song Poem Featured on The Slowdown!—Birds in Home Depot - February 7, 2023

- The Rapping in the Attic—Happy Holidays Fun Video! - December 21, 2022

- Video: Earth Song: A Nature Poems Experience—Enchanting! - December 6, 2022

Sandra Heska King says

I’ve been reading these over and over. Glynn might shake his head at me, but these poems literally take my breath away. They are… breathtaking. I don’t know if poetry enslaved him or if he just settled into its call in spite of the sweat and callouses. Either way, we win.

Will Willingham says

Poems like “Facts” feel absolutely stark to me. Clear, no pretense, no blurred lines. And so unsettling even while it makes me feel more clear-minded.

I do think he fully understood the power of poetry, am very grateful he did not resist it. I imagine his hands were utterly calloused.

Rick Maxson says

Calloused hands remind me of the detail in the movie Shakespeare in Love of his ink stained fingers and hands.

I love the use of slashes in Gelman’s poetry. It reminds me of Dickinson’s dashes.

Laura Lynn Brown says

I love the slashes too. It makes those things between the slashes exist simultaneously instead of sequentially.

Will Willingham says

The slash marks actually don’t appear until his later poems and are understood by some to be an expression of his grief, almost like cut marks. This is remarkable to me.

Maureen says

“Facts” offers up such a marvelous metaphor. Gelman is one of the many great poets – Denise Levertov and Adrienne Rich also instantly come to mind – who understand the power of words and beautifully deploy them in protest.

And Gelman’s right that poetry isn’t for the faint-hearted. What one does with words, with a poem, can lead to brutal response and exile, as is so clear from the abbreviated list of poets I included in my piece of several weeks ago. Poems especially seem threatening to dictators. (I’m so pleased to see on FB the many calls for poetry protesting the new Administration.)

Great post, LW! Excellent choices of poems to illustrate your points.

Will Willingham says

I actually feel a little weak after I read Facts, which I’ve been doing, oh, every few days lately. It is the finest demonstration of the power of words I may have seen.

It’s always striking to consider, too, that while so many lament that poetry is “too hard” to understand that exactly as you point out, it’s led to the exile of many poets. So perhaps it is not so hard to understand, after all.

Michelle Ortega says

No line of poetry has overthrown any dictator, but the poet, the one who bears witness to the dictator, compelled to record the experience for others to connect, to digest and to integrate into their own experience, the words, the blood, prevent the dictator from having the last word. Just as the words project the never-ending beauty, it seems as though Gelman is “enslaved” by his passion, his call, to record the mystery of human experience in verse.

Perhaps he wrestled with his own drive to compose his verse, wondering if his occupation as poet was serious enough for what he observed in the world around him? And that tension is revealed in these poems.

Will Willingham says

I think that tension is most definitely there, Michelle. The wondering if words are enough. And yet I think he also knew just what could be accomplished with them. I do believe, with you, that even if they don’t accomplish the particular aim, bearing witness is a worthy enough pursuit.

Laura Lynn Brown says

I keep going back to the shooting imagery in “The Art of Poetry” and “Facts.” In the first, there’s that stunning last line: “obscure faces write my verses like bullets firing at death.” It makes me think of executions, the gunshot the last thing heard by the victim. But death itself is the target here, and it suggests that a poem can have aim and velocity.

That appears again in “Facts”; the “he” in the poem opens a line of poetry and packs it like a gun, with beauty as his ammunition. He squeezes the first line like a trigger and aims. And there’s that last line, “the/ shots fired by neverending beauty.”

Do the dictators and bureaucrats ever think about beauty? Can they recognize it? Is it one of the things they can’t legislate or execute? These dark times require both shots and beauty, both the stone and the bright glow in autumn, or dim glow in January.

Maureen says

That intersection of beauty and violence occurs throughout Gelman’s work, which, I think, adds such depth to such spare writing. We can observe both but control neither’s existence in our lives. What happens when we extend that metaphor that “Facts” evinces? A poem goes out into the world and is no longer one’s own. Fire the weapon, and it’s impossible to stop the bullet until it finds its target.

When I re-read Gelman, I think often of Picasso’s ‘Guernika’ (‘Guernica’) and the effects it had.

Megan Willome says

I like the woman in the leather apron in “Time Schedules” who is “hammering verbs together.”

Rick Maxson says

The dictator outlives the poetry of his age, yes, but poems are the stones that rise, one on another, as mountains. It is the soughing of the seas making the hand that holds them. Poetry has the long, slow gait of a prodigious beast. Their migration leaves prints in their absence, to be filled by the feet to follow.

Ben Lerner, in his narrow book “The Hatred of Poetry” speaks to the proclamations of poetry’s demise or atrophy in the modern and contemporary fields of time. He notes James Longenbach’s stating ten years ago that in the midst of “the death of poetry” talk there were approximately 300,000 websites in existence for the reading and writing of poetry.

These sites range from those catering to the decanting of the angst of teenage love to those dedicated to the power of poetry to open the world through the reading and writing of poems and strengthen our resolve to live as awake beings. Brenda Hillman writes in her essay, “Cracks in the Oracle Bone” that every effort at poetic creation is of value, a step in the revolution of our thinking, “the shots fired by neverending beauty.” The origins of “Cracks in the Oracle Bone” rise from a practice of divination in Chinese culture from cracks in the bones of ancestors. Hillman notes that it is thought to be, in part, the source of the Chinese language ideographs.

Speaking to the overthrowing of dictators (and this is my interpretation) Hillman writes about an article she read on the recent practice of mountain women of Southern China who developed a secret language, based on oracle bone divination, to communicate with one another in a form men could not interpret.

Authoritarian men are not usually poets. Good poetry is often difficult. It arises from spaces and places in between, in the cracks of the world-at-large. But it is not something belonging to authoritarian “rational” irrationality to be falsely understood. Poetry is slow. It merely invites us to see the ‘joins’ of the world and its “separations” and enter there.