In high school, I studied three assigned novels by Charles Dickens (1812-1870). In ninth grade, our English class read Great Expectations. In tenth grade, we studied A Tale of Two Cities. And in 12th grade, it was David Copperfield.

Over the course of some 40+ years, what I remembered most about David Copperfield were the two villains, James Steerforth and Uriah Heep, and the terrible thing Steerforth did (but only that Heep was an evil character). But a few visits to the Charles Dickens Museum in London over the past five years led me back to David, his childhood nurse and housekeeper Peggoty, Dora and Agnes, Heep, David’s Aunt Betsey Trotwood, Mr. Murdstone and his odious sister, and Ham and Emily, and, well, to story of David from birth to manhood.

The original 1849 cover

What a crackerjack story it is! It’s about good and evil, kindness and venality, family real and by circumstance, avarice, power, and perhaps most of all, love. It’s filled with memorable characters with wonderful and distinctive names. It captures the manners and foibles of the time, as only Dickens could do. It tells a story of the working and middle classes in the first half of 19th century England. And it speaks to the nobility and the depravity of the human condition.

The novel is first the story of David. Its official title is The Personal History, Adventures, Experience and Observation of David Copperfield the Younger of Blunderstone Rookery. He is writing an account of his life, long after the events have passed. He records and reflects; he makes notes and what we might called in-text annotations. David Copperfield is Dickens at his most aware of the act of writing.

But it’s much more than David’s story. David also tells the story of his idolized schoolmate James Steerforth, some years older and far more mature. David and Steerforth pass in and out and in again of each other’s lives, and David cannot foresee the tragedy Steerforth will bring with him.

The novel is also the story of the Wickfields, Agnes and her lawyer father, with whom David boards for a time in Canterbury. The law practice clerk is Uriah Heep, and Davis tells the story of how over a course of years Heep exerts and gains control of Mr. Wickfield, his law practice, and, Heep hopes, ultimately even Agnes.

“The Waiter and I” by Hablot Knight Browne (Phiz)

As was the custom at the time, David Copperfield was published in monthly installments between May 1849 and November 1850. In late 1850, it was published in complete novel form. It is a long story—I read the 1994 illustrated edition published by Oxford University Press, which runs to 876 pages. (I can remember the thick paperback edition we read in senior English, with its yellow-orange cover. Some 35 high school seniors could be seen carrying that paperback almost everywhere at school, reading a few pages here and a few pages there, desperate to finish it in time for the writing the paper and taking the test.)

The serialized version and its published book form included the illustrations by artist Hablot Knight Browne, who illustrated many of Dickens’ works and was known by the nickname of “Phiz.” My edition included these illustrations, and they are charming, striking a sense of wonder about what appealed to reading audiences in mid-19th century Britain (and America).

What only became understood long after its publication was that it is the most autobiographical of all of Dickens’ novels. Dickens never said much about his childhood until very late in his life. Today, we take the story of his child labor in the blacking factory for granted (his father was in debtors’ prison), but it wasn’t generally known to his first readers. And Dickens’ father indeed makes an appearance in the novel as Wilkins Micawber, a genial and kind man with a devoted wife and large family who stays barely one step ahead of his creditors.

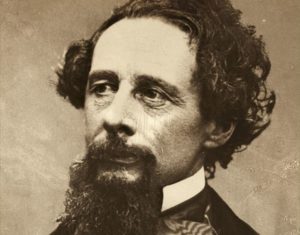

Charles Dickens about 1850

David’s birthplace of Blunderstone is based on the town of Blundeston in Suffolk. While there is no direct Dickens connection, the town remains quite proud of its literary heritage and connection to the novel.

David Copperfield could easily be called Dickens at his best. The story has withstood the test of time. It is filled with familiar themes, wonderful details, and wildly individualized characters whose names are simply brilliant. It is a story worth reading and rereading. You will laugh and cry, feel your blood run cold, and feel your heart break when certain characters die. Just as Pickwick Papers is critical to understanding why Dickens became popular in the first place, David Copperfield explains why his stories have endured.

Photo by Phillippe Put, Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post by Glynn Young, author of the novels Dancing Priest and A Light Shining, and Poetry at Work.

__________________________

“I require all our incoming poetry students—in the MFA I direct—to buy and read this book.”

—Jeanetta Calhoun Mish

- Longfellow’s “Paul Revere’s Ride”: Creating a National Legend - April 17, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Katie Kalisz and “Flu Season” - April 15, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Michelle Ortega and “When You Ask Me, Why Paris?” - April 10, 2025

Bethany says

Thank you for this book recommendation, I haven’t read it yet, but it’s actually on my bookshelf.

I remember reading and loving dear Oliver Twist. Dickens had quite a gift for creating characters that warm up the empathy pot.

Sherry says

I love David Copperfield. I have wanted to re-read it for a while now, but it would take so much time away from books that I haven’t yet read.

Marilyn Yocum says

All these characters have a place in my heart. Your mere mention of their names brings them back. Aw, the Micawbers….something is bound to turn up! Dickens is my favorite author, BUT…true confession….it’s taken me years to stop writing long, one-sentence paragraphs with one dependent clause after another. 🙂