Here I am working on only my third barista badge. I have a ways to go, but I can’t look too far ahead. If I do, I’ll panic and start muttering in the streets about having to recite all “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock” at once. This is a long poem, so I know it’ll take time, but I really thought I’d be further along by now. Part of the problem—and maybe it’s not really a problem—is something Glynn Young said, “Discovering poetry and poets can be something of a rabbit trail.”

I’ve been chasing rabbits.

Because I’m paying more attention to the words, I’m seeing things I’ve missed before—or just skipped over. I’m noticing rhymes and repetitions, though I haven’t yet figured out a pattern. I got sidetracked with researching sawdust restaurants and oyster shells. I even phoned a few friends. It turns out that sawdust was sprinkled on floors to absorb spills (and smells?) from, shall we say, rowdy patrons. And oysters were a cheap eat—as well as a possible aphrodisiac. Clearly Prufrock wasn’t inviting me on a date to the most savory part of town, which makes me curious about these women and this room and Michelangelo.

I took a break and backed up to that Italian stuff, I mean the epigraph, a “funny literary convention” that excerpts lines of another work to introduce a piece of writing. I don’t understand a word of it (yet), but I know it comes from Dante’s “Inferno.” It seems wise to read that to better understand, so I downloaded a Kindle edition of The Divine Comedy translated by—wait for it—Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. I need to sit with that revelation for a bit. Am I the only one who didn’t know the dude who wrote “The Song of Hiawatha” and “Paul Revere’s Ride” also did translation? In Italian?

Jumping down to the second stanza (after Michelangelo’s refrain):

The yellow fog that rubs its back upon the window-panes,

The yellow smoke that rubs its muzzle on the window-panes,

Licked its tongue into the corners of the evening,

Lingered upon the pools that stand in drains,

Let fall upon its back the soot that falls from chimneys,

Slipped by the terrace, made a sudden leap,

And seeing that it was a soft October night,

Curled once about the house, and fell asleep.

It took me more than a minute to get straight in my head that it was the yellow fog that rubbed its back upon the window-panes and the yellow smoke that rubbed its muzzle on the window-panes.

Struggling to get that correct made me want to curl around the house and go to sleep like my yellow cat. But, by Thomas, I got it. Then, in the next stanza, it’s the yellow smoke that’s rubbing its back on the window-panes. That reversal disturbed my universe for more than a minute.

While I was dealing with this foggy situation, I thought about Carl Sandburg’s poem.

Fog

The fog comes

on little cat feet.

It sits looking

over harbor and city

on silent haunches

and then moves on.

— Carl Sandburg

See? Rabbit trails.

Some say Sandburg sometimes copied other poets and that he published “Fog” a year after “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock.” It might be true. As the story goes, Eliot was not a fan of Sandburg’s poetry. Sandburg thought Eliot had no sense of humor. And I get the idea they were politically polar opposites. One day they both ended up in their publisher’s office at the same time. The publisher, fearing fireworks, tried to confine them to separate offices while he, in his words, went “to the John or something.” He says that when he came back just five minutes later, “Carl was sitting in my office, right next to Eliot, and Eliot had a big grin on his face. Carl said, ‘Bob, look at that man’s face. Look at the suffering in that face.’ And Eliot shot back, ‘You can’t blame him for the people who ride on his coattails.’”

Now where was I? Oh yes. Working on my third barista badge. I’ve got time. Indeed there will be time. And when I complete this section, I’ll treat myself to some toast and tea.

Photo by Rifca Peters, Creative Commons license via Flickr. Post by Sandra Heska King.

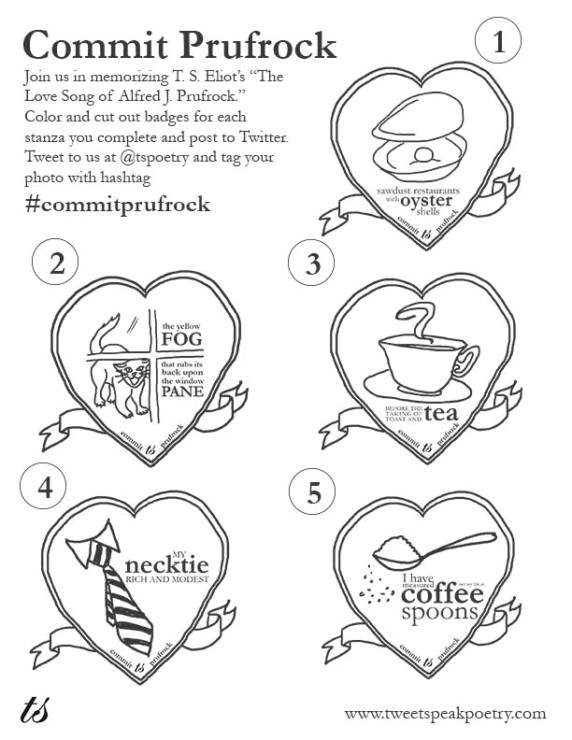

Want to commit Prufrock with Sandra? Download your own Committing Prufrock Poetry Dare Printable Barista Badges that you can cut out and color to celebrate all 15 sections as you memorize them. Tweet a photo with your badge to us at @tspoetry and use the hashtag #commitprufrock.

__________________________

“I require all our incoming poetry students—in the MFA I direct—to buy and read this book.”

—Jeanetta Calhoun Mish

- 50 States of Generosity: Rhode Island - June 2, 2025

- 50 States of Generosity: Iowa - April 7, 2025

- 50 States of Generosity: Montana - January 27, 2025

L.L. Barkat says

This delights! 🙂

Your daring is producing more daring from within. How cool is that?

Sandra Heska King says

This is seriously fun. Who knew?

Glynn says

Longfellow is not popular today because (a) he wrote some poems about patriotic themes and (b) his poetry rhymed. This likely says more about us than it does about Longfellow.

Eliot’s “Prufrock” is considered by many to be the most important poem of the 20th century because everything changed after it was published. It was published in 1915 by Poetry Magazine, after Ezra Pound badgered them into printing it. Poetry buried it at the back of the issue.

But its influence has been profound.

And Longfellow is still worth reading.

Sandra Heska King says

Thanks for this background, Glynn. And for another rabbit trail to follow. (I really like Longfellow. What does that say about me?)

Maureen says

You deserve more than another badge for doing this. Love what you’re doing and discovering and learning.

Sandra Heska King says

So… memorization becomes more than memorization. But… I still can’t picture myself reciting the entire thing. Fiddle-dee-dee. I’ll think about that tomorrow.

Sandra Heska King says

And thank you. I hope you’re on Italian standby. 🙂

Bethany says

Beautiful, Sandra. Love how the breeze rises up through your hair and the branches as you finish—as if to applaud. I’m clapping too.

Megan Willome says

Nice observation, Bethany!

Sandra Heska King says

I love that, Bethany. Thank you!

Will Willingham says

This is so great. 🙂 This is why we give people poetry dares. Because there is always more to it than what you are dared. It’s what you bring to it, what you go looking for, what you stumble upon.

So glad you are doing this, and bringing us along. 🙂

Martha Orlando says

Such an achievement so far, Sandra! You’re tempting me to go down a few rabbit trails myself.

Blessings!