Dystopia is a powerful theme in contemporary culture. Consider the Mad Max movies, The Walking Dead, The Hunger Games, or even the fantasy series Game of Thrones. One could argue that the fictional genre of fantasy is often characterized by a sense of dystopia, post-apocalyptic worlds in which people must survive by brute power and cunning. British poet Matthew Duggan takes the idea of dystopia a step backward, however, and applies it to the world and landscape surrounding us today.

Dystopia 38.10 contains some 98 poems, most of which suggest a sense of dislocation, dystopia, the idea that life and the landscape around us have changed, almost while we weren’t watching. The changes can be physical, social, cultural, or political, or perhaps even a combination of all of these.

“London is burning” says one poem, amid bonfires, charred effigies, and the halting of a crowd wandering in aimless direction. “The Asylum” is another kind of dystopia, as its residents “reside for eternity in bedlam.” The landscape is a “wasteland, ” says “Dystopia, ” as cameras scan “the flesh and ashes of dead shopping malls.”

These descriptions do not sound like a fantasy world suitable for inspiring television series. Instead, they sound disturbingly like contemporary life. Consider the poem “Langharne.”

Laugharne

sound of a pony’s hooves scraping against granite,

following the forest to a road of open borders

guarded by rooks that thread the castle remains.

I walk on the shill of black air

sills of light like children jumping for a higher shelf,

peaking bright pocket of sun

crowning the morning with the crispy repeats of dew.

Reaching an ivy smouldered cabin

window smeared with an amber moss,

a writing desk levelled to a vista of trickling water

a pen cushioned in age and inkling ash.

A morning in black hoods of cloud

where a moon lights up a castle like a cathedral,

I saw discarded fishing wrecks sleeping in dribbles

simmered by a slow tide of blue and wide sparks.

Matthew Duggan

Laugharne is in Wales and where the poet Dylan Thomas lived until his death in 1953. One of the sites it’s known for is Laugharne Castle. Duggan is envisioning a landscape of “black air, ” a cabin covered in ivy and with windows “smeared with an amber moss, ” “black hoods of clouds, ” and discarded fishing wrecks. That last line—“simmered by a slow tide of blue and wide sparks”—is particularly striking.

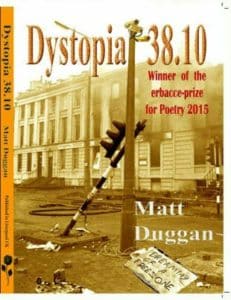

Matt Duggan was born in Bristol, England, in 1971 and lives there today. His poems have appeared in numerous online and print journals, including Indiana Voice Journal and Ink Sweat and Tears. He started and still hosts a spoken word evening at the Hydra Bookshop in Bristol and is co-editor of the political poetry magazine The Angry Manifesto. Dystopia 38.10 won the 2015 Erbacce prize for poetry.

Dystopia 38.10 is filled with unsettling connections and disturbing ideas, made more so by the vivid images and descriptions. The poet and the reader are taking a journey together, and it is a harrowing one because it is so familiar.

Related: Matthew Duggan’s Underworld: The Modern Orpheus.

Photo by Pai Shih Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post by Glynn Young, author of the novels Dancing Priest and A Light Shining, and Poetry at Work.

__________________________

“I require all our incoming poetry students—in the MFA I direct—to buy and read this book.”

—Jeanetta Calhoun Mish

- Poets and Poems: Katie Kalisz and “Flu Season” - April 15, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Michelle Ortega and “When You Ask Me, Why Paris?” - April 10, 2025

- Robert Waldron Imagines the Creation of “The Hound of Heaven” - April 8, 2025

Bethany says

Thanks for exploring this collection and sharing your insights with us. I appreciate your mentioning where Laugharne is: Wales (we have ancestors from there). It’s interesting to have a bit of background when reading the featured poem and the rest of the post.

How unfortunate that there is a connection between these dystopian scenes and life in 2016. Hopefully we will all continue to work together toward something better, “like children jumping for a higher shelf.”