One of the things I’ve learned from writing here at Tweetspeak Poetry is that, when it comes to poetry, the articles you write have a way of continuing to live. They may be reposted or republished on other sites, and they can lead you to continue reading more work by the poets you write about. Consider the poets Norman Nicholson and Frank Stanford.

I was reading A Poet’s Guide to Britain by Owen Sheers, which I wrote about in July. It was there I discovered Nicholson (1914-1987) and his beautiful poem “Scafell Pike.” I did some digging and was able to find several of his poetry collections through used book dealers (mostly in the UK). And then I wrote in August about how he wrote about the landscape and environment of northern England, the Lake District, and the northwest English coast.

Norman Nicholson

In 1951, Nicholson published a biographical and literary study of the English poet William Cowper (1731-1800) that is still considered the best study ever done of the poet. I was only vaguely aware of Cowper, but was intrigued enough (65 years is a long time for a literary study to remain “the best”) to get hold of a copy of the book. And it is a gem.

The study is relatively short – 165 pages – but it is packed with understanding and insight. Associated with the religious revival of the middle and late 18th century in Britain, Cowper wrote numerous poems used as the lyrics for hymns. But his work went far beyond that. Nicholson devoted considerable discussion to Cowper’s major work, The Task; his ballads, like The Diverting History of John Gilpin; and his other poetry. And Nicholson argues that Cowper heavily influenced both William Blake and the Romantic poets.

Here is one of Cowper’s shorter poems, and one can see why a poet like Nicholson, who wrote so much about nature, would be attracted to Cowper.

A Comparison

William Cowper by Lemuel Francis Abbott

The lapse of time and rivers is the same,

Both speed their journey with a restless stream;

The silent pace, with which they steal away,

No wealth can bribe, no prayers persuade to stay;

Alike irrevocable both when past,

And a wide ocean swallows both at last.

Though each resemble each in every part,

A difference strikes at length the musing heart;

Streams never flow in vain; where streams abound,

How laughs the land with various plenty crown’d!

But time, that should enrich the nobler mind,

Neglected, leaves a dreary waste behind.

Nicholson loved the Lake District, and in 1991, a posthumous collection of his writings about the area were published under the title of Lakeland: A Prose Anthology. The book is essentially a collection of journal entries, mostly short observations on the landscape, the coast, the lakes, animals, humanity’s impact on the natural environment of the area, villages and towns, the tourist track, and people who explored the area. A chapter entitled “Poets and Writers” includes observations on Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Robert Southey, Thomas De Quincey, and John Ruskin, but is mostly about William Wordsworth. The Lake District is clearly an area where land and poetry meet.

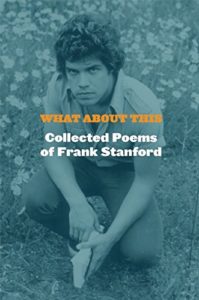

It took some waiting, but I was finally able to get my hands on What About This: Collected Poems of Frank Stanford. Collected and edited by the literary critic Michael Wiegers, it was published in 2015 by Copper Canyon Press and includes the texts of all of Stanford’s published collections as well as a considerable number of poems that were unpublished. (It also has an intriguing note written inside the front cover: “If found, please return to Room 308, Hotel New Orleans, Eureka Springs, Arkansas, ” followed by a name and an address in Rogers, Arkansas.)

Stanford did incredible things with images, such as in this poem published after his suicide.

Dreamt by a Man in a Field (1979)

I am thinking of the dead

Who are still with us.

They are not like us, they are

Young and beautiful,

On their way in the rain

To meet their lovers.

On their way with their dark umbrellas,

Always laughing, so quick,

Like limbs flying back

Ina boat before night,

So constant,

Like the glass floats

The fishermen use in Japan.

But for them there is no moon,

For us the same news

We do not receive.

Discovering poetry and poets can be something of a rabbit trail. An anthology leads to a poet leads to another poet. A collection by one poet leads to a collection by another.

I find this rather wonderful.

Photo by Jeremy Lelievre, Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post by Glynn Young, author of the novels Dancing Priest and A Light Shining, and Poetry at Work.

__________________________

“I require all our incoming poetry students—in the MFA I direct—to buy and read this book.”

—Jeanetta Calhoun Mish

- Longfellow’s “Paul Revere’s Ride”: Creating a National Legend - April 17, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Katie Kalisz and “Flu Season” - April 15, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Michelle Ortega and “When You Ask Me, Why Paris?” - April 10, 2025

Mary Harwell Sayler says

Glynn, it’s such a joy to find another poet who truly loves poetry in all its forms and enjoys discovering new or unheard voices. Thanks and blessings for enthusiastically sharing your “finds.”

Glynn says

Mary – thanks so much for the comment. Poetry is always a journey of discovery.

L.L. Barkat says

Little poetic maps. 🙂

I find it wonderful, too, that you follow these one to another. And that people like Maureen come along in our comment boxes and reveal whole related bookshelves that link one to another. Simple richness, for which I’m grateful.

Glynn says

This connectedness – it’s the best part of the worldwide web.

Maureen says

Yours is the equivalent of a poetic “6 degrees from. . . .’

Glynn says

And sometimes it’s even fewer degrees! Thanks for the comment, Maureen!

Sandra Heska King says

“Discovering poetry and poets can be something of a rabbit trail.”

I’ve found this true. In fact, I’m writing about one of those trails right now. (Sometimes I get dizzy on the trail wondering which detour to follow next.)

Glynn says

Oh, but the trail can be great fun! Even occasionally getting lost can be fun.

Bethany R. says

“(It also has an intriguing note written inside the front cover: ‘If found, please return to Room 308, Hotel New Orleans, Eureka Springs, Arkansas,’ followed by a name and an address in Rogers, Arkansas.)”

Eureka Springs, Arkansas? Hm. I think I see a little rabbit trail over there through the brush. Isn’t there a poet here at Tweetspeak that enjoys exploring that very city?

https://www.tweetspeakpoetry.com/2016/02/26/memoir-notebook-searching-for-arkansas/

https://www.tweetspeakpoetry.com/2016/03/18/best-buildings-carnegie-library-eureka-springs-arkansas/

I wonder what he knows about Room 308…

Glynn says

There was also a name, which I left off, and it wasn’t that Tweetspeak poet. I suspect this had to do with Frank Stanford being so strongly connected to Arkansas, and that part of Arkansas in particular.

But I’m always intrigued by book inscriptions like that. The William Cowper biography by Nicholson, for example, apparently lived for a very long time in the central library of Belfast, Northern Ireland. It made its way to England, and sat in England for some extended period of time, before this odd person in suburban St. Louis found and ordered it on Amazon. So it leaped the Atlantic Ocean and came to rest in the middle of the United States.