The poetry of Forward Prize winner Tiphanie Yanique may redefine words like “arresting, ” “jarring, ” and “mind-altering.”

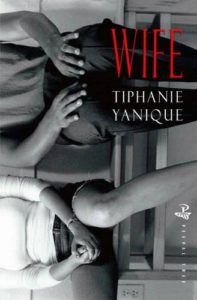

Yanique’s Wife won the Forward Prize, given by the Forward Arts Foundation in the United Kingdom, for best first collection. As the title suggests, it’s a collection of poems about becoming a wife, being a wife, thinking and rethinking the meaning of the idea of wife—colored and shaped by a Caribbean context.

We find the drudgery of housework and considerations of cheating on one’s husband. We find the romance of elopement and musings of divorce in a happy marriage. We find musings about one’s own family and experiences in common with all families. And by the end of the collection we understand that all of these seeming contradictions are held together, even if in tension, in every relationship and marriage.

Consider this metaphor for marriage—what happens inside a distressed airplane.

We fall out of the sky

I will always fight for us to sit side by side.

If the cabin pressure goes

and the plane plummets like a suicide,

we will learn together what the seat belts are for.

One by one the other passengers will give in

to oxygen, then its absence. But not me,

please know, not me.

I will tie your belt around our waists.

In the coma you cannot help,

I will open your mouth to give you my breath

as the windows burst in.

Perhaps we will never know if

we are dead or alive.

The poem is an unusual description for commitment in a marriage, but the basic elements are there—fighting to stay together, refusing to give up, the giving of breath (and life), the sharing of a seat belt. Those final lines, “Perhaps we will never know if / we were dead or alive, ” suggest that the knowing may not actually be important. Instead, what’s important is the being together, the shared experience, and the commitment implied. (The phrase that grabbed me by the throat was “the plane plummets like a suicide.”) These ideas set against each other are found consistently throughout the poems.

Tiphanie Yanique

Yanique, a professor in the MFA program at New School in New York City, is the author of the novel Land of Love and Drowning (2015); the long poem I Am the Virgin Islands (2012); a collection of short stories, How to Escape from a Leper Colony (2010); and the short story chapbook The Saving Work (2007). She is also the co-editor of the poetry anthology Another English: Anglophone Poems from Around the World (2014). She has received the 2011 Bocas Award for Caribbean Fiction, Boston Review Prize in Fiction, a Rona Jaffe Foundation Writers Award, a Pushcart Prize, a Fulbright Scholarship and an Academy of American Poet’s Prize.

Wife challenges our notions of what marriage (and being a wife) means, but ends up reaffirming the idea of commitment.

The Forward Arts Foundation also gives an annual prize for best single poem. This year, Sasha Dugdale received the 1, 000-pound award (about $1, 300) for “Joy, ” published by PN Review Literary Magazine. Read the poem to see how a poem’s title can both contradict and affirm the poem itself.

Related:

Forward Prize: Measures of Expatriation by Vahni Capildeo

Photo by simplydiandra, Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post by Glynn Young, author of the novels Dancing Priest and A Light Shining, and Poetry at Work.

__________________________

“I require all our incoming poetry students—in the MFA I direct—to buy and read this book.”

—Jeanetta Calhoun Mish

- Longfellow’s “Paul Revere’s Ride”: Creating a National Legend - April 17, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Katie Kalisz and “Flu Season” - April 15, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Michelle Ortega and “When You Ask Me, Why Paris?” - April 10, 2025

Will Willingham says

Jarring is right. True to form, I read your comments on the poem before reading the poem, and even then, jarring. 🙂 So glad you chose that poem. Thanks for these introductions to the Forward Prize winners, Glynn.

Glynn says

Thanks for the comment, LW. I read that poem at least five times, and each time I saw it more and more as a very intense love poem.

Maureen says

I wonder if the selection of ‘Wife’ as the title’s collection sets readers up for considering the poems from a particular perspective. For example, in ‘We fall out of the sky’, we don’t know the gender of the speaker; it could as easily be a male as a female voice. If we accept it as female voice, then it’s interesting to consider the implicit senses, in the context of “wife”, as female action-taker/doer/protector/saviour – a kind of feminist reading, if you will. And, if we don’t carry implicitly with us the idea of a wife and her roles, the poem, being metaphorical, could be read as about something other than marriage, including, for example, a mother’s love for her child.

I love that a poem can challenge one’s thinking as this poem does.

I’ll be putting this collection on my list of reads.

Maureen says

I meant to write, ‘… as the collection’s title’.

Bethany R. says

“I will tie your belt around our waists.”

Intentional commitment. Powerful voice.

Sandra Heska King says

“If the cabin pressure goes

and the plane plummets like a suicide,

we will learn together what the seat belts are for.”

This whole poem is a keeper. And I’ve asked for an Amazon gift card for Christmas…

Rick Maxson says

Thank you once again, Glynn, for bring a book of poems and your perceptions to our attention. I am certainly ordering this one. Marriage is one of the most challenging (at times) and rewarding (more than challenging) relationships we humans can commit to. Yanique’s poem for me displays the raw emotions of marriage. Its confusions, its clarities, its temptations, the strengths it imparts and the weaknesses it reveals. The final lines, “Perhaps we will never know if we are dead or alive” speaks to me of how marriage can require the abandonment of control—the practice to let it be.

In our contemporary culture we have so often lost sight of the seriousness of becoming married. It is a sacrament (And what meaning does that word carry in today’s world?), not to be taken lightly for what it can give and what it requires for what it can give.