Poet Don Paterson is a presence in British letters. He’s known for his poetry, his criticism, his dramas (including radio dramas), his anthologies, and his aphorisms. Patterson has won most if not all of the major British poetry prizes. He’s won the T.S. Eliot Prize twice. His work has been lauded by such diverse readers as mystery writer Ian Rankin, American poet Billy Collins, and English novelist A.S. Byatt. He received the Order of the British Empire (OBE) in 2008.

Born in Dundee, Scotland, in 1963, Paterson teaches at the University of St. Andrews and serves as the poetry editor for the London publisher Picador. He has translated Rainer Maria Rilke’s Orpheus; written critical commentaries and three books of aphorisms; and edited and co-edited general and thematic poetry collections. He’s also co-authored the guidebook for a 2008 exhibition of the paintings of Alison Watt at the National Gallery in London.

Like I said, he’s a presence.

His poetry tends to the formal, often with rhyme and meter. Not that there’s any direct connection, but his poetry was first published about the same time as the New Formalists (i.e., Dana Gioia) gained popularity in the United States. But it’s formal with a significant difference: Paterson is known for both his light and dark humor, and for occasionally writing in Scottish dialect. This poem, for example, offers a rather horrifying subject until you realize that he’s speaking metaphorically about himself:

The Lie (From Rain)

before the house had woken to make sure

that everything was in order with The Lie,

his drip changed and his shackles all secure.

I was by then so practiced in this chore

I’d counted maybe thirteen years or more

since last I’d felt the urge to meet his eye.

Such, I liked to think, was our rapport.

I was at full stretch to test some ligature

when I must have caught a ragged thread, and tore

his gag away; though as he made no cry,

I kept on with my checking as before.

Why do you call me The Lie? he said. I swore:

it was a child’s voice. I looked up from the floor.

The dark had turned his eyes to milk and sky

and his arms and legs were all one scarlet sore.

He was a boy of maybe three or four.

His straps and chains were all the things he wore.

Knowing I could make him no reply

I took the gag before he could say more

and put it back as tight as it would tie

and locked the door and locked the door and locked the door

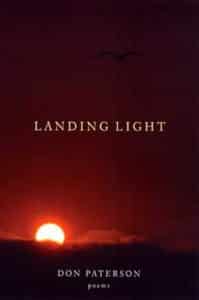

His 2003 collection Landing Light won both the T.S. Eliot Prize and the Whitbread Prize for Poetry. Its 36 poems address Dante, Romulus and Remus, the fabled library at Alexandria, love, acknowledgements to Rainer Maria Rilke, and the idea of place. The range is startling in such few poems as the collection includes, but they are each uniformly fine.

His books of aphorisms seem more like footnotes to his poetry that what they actually are. In The Book of Shadows, he includes sayings (and often witticisms) on love, sex, male-and-female relationships, writing, poetry, and more. Two of my (many) favorites: “Writers dream of discovering some dead genius they can plagiarize in absolute secrecy, ” and “The emphasis is all wrong; the tale of his life will read like a great book underlined by an idiot.”

Don Paterson

Paterson’s poetry collections include Nil Nil (1995); God’s Gift to Women (1997); The Eyes (1999); The White Lie: New and Selected Poetry (2001); Landing Light (2003); Rain (2009); Selected Poems (2012); and 40 Sonnets (2015). In addition to the T.S. Eliot Prize and the Whitbread Prize, he’s won the Geoffrey Faber Memorial Prize, the Forward Prize for best first collection, the Eric Gregory Award, three awards from the Scottish Arts Council, and a Creative Scotland Award. He’s also an accomplished jazz guitarist.

Don Paterson is an important voice in British poetry and letters. He writes of both the light and the dark in life and in ourselves, and he writes to find the true.

Photo by Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post by Glynn Young, author of the novels Dancing Priest and A Light Shining, and Poetry at Work.

__________________________

“I require all our incoming poetry students—in the MFA I direct—to buy and read this book.”

—Jeanetta Calhoun Mish

- Poets and Poems: Forrest Gander and “Mojave Ghost” - March 27, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Siân Killingsworth and “Hiraeth” - March 25, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Donna Hilbert and “Gravity” - March 20, 2025

Bethany says

Love that aphorism by Paterson: “The emphasis is all wrong; the tale of his life will read like a great book underlined by an idiot.”

Glynn says

He does sound like a more erudite Mark Twain.

Laura Lynn Brown says

What a chilling poem. Especially the repetition in the last line.

Rick Maxson says

Thank you once again, Glynn, for another great review. I rely heavily on you as a guide to where I should spend my poetry book money.

I’m with Laura on that sample of Paterson’s poetry.