Whan that Aprill with his shoures soote

The droghte of March hath perced to the roote,

And bathed every veyne in swich licour

Of which vertu engendred is the flour,

Whan Zephirus eek with his sweete breeth

Inspired hath in every holt and heeth

The tendre croppes, and the yonge sonne

Hath in the Ram his halve cours yronne…

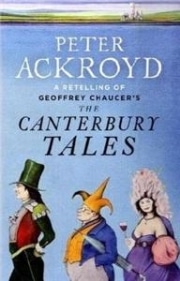

Thus begins the first great English poem. The Canterbury Tales by Geoffrey Chaucer (circa 1343-1400) wasn’t the first poem in what we call Middle English, nor did it cause English to become the official language of the British Isles. What it did do, says author Peter Ackroyd in his modern English prose translation, was mark the emergence of English as the language that was becoming what most people spoke. The royal court still conducted its business in French, but that, too, was changing.

It is a work that stopped as a work in progress. Chaucer completed the General Prologue and less than a third of the planned 120 tales, stories told by a group of pilgrims traveling to and from St. Thomas Becket’s shrine at Canterbury Cathedral. The pilgrims represent virtually all levels of society – merchants, knights, religious figures, tradesman, lawyers, doctors, and more. Chaucer didn’t confine himself to men—in fact, the Wife of Bath is one of the most memorable characters in the entire poem, with a prologue that is the longest of any of the tales.

Americans are usually introduced to The Canterbury Tales in high school. It’s not a work for children. I read and was taught the General Prologue as a high school freshman; we read the entire work in senior English class. I attended an all-boys public high school, and no other work experienced the enthusiasm that The Canterbury Tales did for a class of 17-year-old boys. We read it in verse (likely the 1951 translation by Neville Coghill, still considered one of the best) and most of the class also bought a modern prose translation.

Our teacher, a sweet, soft-spoken soul in her early 60s who loved English literature, was perhaps the most courageous teacher I had. To teach the tales of the Miller, the Reeve, the Friar, and the Summoner to some 30 teenage boys is, in retrospect, amazing. These four (and others) are ribald, risqué, vulgar, shocking, coarse, and wildly funny. Recently rereading the work, I laughed out loud at the crucial scene in “The Summoner’s Tale, ” in which a corrupt friar experiences well-deserved revenge.

What I did not know was that the manuscripts of The Canterbury Tales are numerous and fragmented. We do not have one completed manuscript that Chaucer left for posterity. Instead, we have fragments, with some tales revised and others left incomplete. It’s clear he was revising as he wrote. The first printed version we have was by William Caxton in 1478, and it was based upon a now-lost manuscript. (A 1985 edition of the Tales translated by David Wright is organized by fragments, and gives a good idea of what scholars and translators have to deal with.)

Geoffrey Chaucer

It is still a remarkable work. Chaucer had one of the most varied careers imaginable—royal page, soldier, writer, customs house administrator, songwriter, landlord, diplomat, member of the king’s household, and, of course, poet, among others. Latin may have been the language of the church and French of the court, but Chaucer chose to write in English. English was on the rise, and Chaucer’s writing rose with it. And his insights and understandings of people at all levels of society likely comes from that varied and extensive career.

Coghill’s 1951 translation is still in print; I saw it at a Barnes & Noble just three weeks ago. And Ackroyd’s “retelling, ” as he calls it, is an excellent modern prose translation. Be forewarned: Chaucer’s Middle English might mystify us but Ackroyd’s English makes words very explicit. We can imagine why Chaucer’s songs were sung all over England during his lifetime.

And it’s no wonder that Chaucer was popular with a class of 17-year-old boys.

Here is the modern English of those opening lines of the General Prologue:

When April with his showers sweet with fruit

The drought of March has pierced unto the root

And bathed each vein with liquor that has power

To generate therein and sire the flower;

When Zephyr also has, with his sweet breath,

Quickened again, in every holt and heath,

The tender shoots and buds, and the young sun

Into the Ram one half his course has run…

This week, Tweetspeak Poetry is joining with the Forward Arts Foundation to help celebrate National Poetry Day UK, on Oct. 6. Come back tomorrow for a related article highlighting Random Act of Poetry Day, and on Thursday for the official celebration.

Photo by Mike Beales, Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post by Glynn Young, author of the novels Dancing Priest and A Light Shining, and Poetry at Work.

__________________________

“I require all our incoming poetry students—in the MFA I direct—to buy and read this book.”

—Jeanetta Calhoun Mish

- Poets and Poems: Forrest Gander and “Mojave Ghost” - March 27, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Siân Killingsworth and “Hiraeth” - March 25, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Donna Hilbert and “Gravity” - March 20, 2025

Maureen says

You took me back a bit in time. I took two semesters in Chaucer and, later, the inaugural course at my college of medieval narrative, both taught by a great professor, both in the English used at the time of writing. And that was more than 40 years ago.

I also took two semesters in Shakespeare, who claims so much more fame.

Glynn says

That’s taking you back – what – 10 years?

In college, we had to read the Prologue in the original Old English. Yes, English had changed a bit since the 14th century.

Thanks for the comment!

SimplyDarlene says

Oh! Chaucer was my first dip into poetry via a high school English class. In addition to the readings and discussions, we had to choose a friend and poetically personify him/her into one of the pilgrims. (I bet I still have mine tucked away in a trunk. At least I hope I do.) I wrote about my best friend, who is now my husband of 22 years.

Crazy how I’d forgotten this until reading your piece today, sir Glynn!

Glynn says

And of course you would have written of him like Chaucer’s Knight. Not the miller or the reeve.

Thanks, Darlene!

Bethany R. says

Fun to read a few lines of Chaucer again. I can see what you mean about the courage of your soft-spoken teacher reading this to high school-age boys. I remember blushing a bit myself at some of the readings and explanations I heard in class—even in college.

It was quite another experience to get to visit St. Thomas Becket’s shrine at Canterbury Cathedral in person—amazing to absorb the reality of this destination and all the history and literature that surrounded it.

Looking forward to the celebration days this week with our friends in the UK…

Glynn says

Bethany, our visit to Canterbury Cathedral in 2012 was a highlight of our trip to England. At 3 in the afternoon, one of the priests announced that it was prayer time, and asked all of us to stand silently. He then invited us to join in reciting the Lord’s Prayer. I was standing in the area of the choir, and next to me was a group of about 30 Japanese tourists (and yes, they all had cameras). When it came time to recite the prayer, every one of them joined in, speaking in English. It was a rather profound moment.