It could be said that the magician was simply doing the very thing he was put on the earth to do: Magic. Amazing, mysterious, impossible magic. How long he had been performing magic is something we aren’t able to know. But it had been long enough, apparently, that making lilies appear from nothing had become commonplace. Too commonplace. On the night the magician made an elephant appear, the lilies were not enough. Confronted with the self-realization that he had “wasted his life, ” the magician sought to rectify the matter the only way he knew, with magic. “He wanted to perform something spectacular, ” Kate DiCamillo writes. (Small-minded though it may be, I should think I would have found lilies, made to appear where there otherwise had been none, to be quite spectacular.)

He had intended lilies; yes, perhaps.

But he had also wanted to perform true magic. (p. 27)

These things that magicians conjure, they do not truly appear from nowhere. Perhaps it is not so noticeable with lilies, but an elephant—she would have to come from somewhere. And when she did, she would surely be missed where she came from (and was no longer) and where she appeared, she would not belong.

The elephant opened her eyes and looked around her and realized she did not know where she was.

She only knew one thing to be true.

Where she was, was not where she should be.

Where she was, was not where she belonged. (p. 15)

But how could this possibly be? If it were indeed true that this feat was the “most astonishing magic of his career, ” the greatest work of a man doing the thing he was born to do, how could it be that such a thing would also bring about so great an injustice as permanently injuring a noblewoman who will never again ask for a front row seat, and uprooting not lilies but an elephant from her not so remarkable (at least in elephant terms) life where she was happily enough living it?

It is often said that “Just becauses you can doesn’t mean you should.” The expression is quite memeable (with even Mr. Bean getting into the act). One could say that the magician should have exercised self-restraint, should have put aside his visions of grandeur, let go his last chance to make a real name for himself as magician fame goes. But to ask him to be satisfied with lilies that would hurt no one, and not cause such suffering for others, it could be argued we would be asking him to do the unthinkable: to be less than he could be.

I assure you, I intended lilies. I intended only a bouquet of lilies. (p. 44)

And yet, The Magician’s Elephant is quick to remind us from time to time, starting with the fortuneteller herself (who, after pocketing Peter Augustus Duchene’s florit and giving him the outlandish revelation that it was an elephant who would lead him to his sister) who says that “the truth is forever changing.”

The elephant, we’ll learn, who was summoned unjustly by the magician in an act of magic we can all agree in hindsight should never have been performed, is the key to Peter finding his beloved but thought-to-be-dead sister. “She lives, ” the fortuneteller says. She lives.

So then, was this an act that should never have been performed? A unimaginable cruelty to the elephant and the noblewoman? Or was this act a great kindness that would reunite the long-separated and lead to a happy life for them both in a home that longed for children?

I am forever wondering as I read this tale, is the truth forever changing, or are multiple things (impossibly conflicting things) true at the same time?

“Wait a while, ” the fortuneteller said. “You will see.”

_____________________

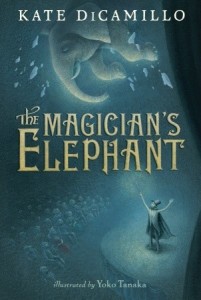

We’re reading The Magician’s Elephant together this month. Are you reading along? Perhaps you would share your observations about the way we exercise our passions and the ever-mystifying nature of truth in the comments.

During our book club, we’ll be exploring some of the overarching themes of the book together, rather than a chapter-by-chapter conversation, so you’ll want to read the whole book before we begin. (Don’t worry, it’s not a book you’ll want to set down once you start anyway.) Then, join us for thoughtful discussion here in the comments again for our last segment, next Wednesday, September 21.

Read last week’s discussion, Naming Names

Read Kate DiCamillo’s Newbery Medal acceptance speech

Get another take on The Magician’s Elephant in What If Natural Selection is Wrong

Photo by Paul van de Velde, Creative Commons license via Flickr. Post by LW Lindquist, author of Adjustments.

- Earth Song Poem Featured on The Slowdown!—Birds in Home Depot - February 7, 2023

- The Rapping in the Attic—Happy Holidays Fun Video! - December 21, 2022

- Video: Earth Song: A Nature Poems Experience—Enchanting! - December 6, 2022

Glynn says

I read what the fortuneteller said, and it raised hackles. She tells Peter that truth is forever changing, but the implication is that she is defining truth as “current circumstances.” Circumstances certainly are always changing. But Peter’s love for his sister did not change. His sense that she was still alive did not change. That was the “truth” in the story.

L.L. Barkat says

That was definitely one of the most beautiful truths of the story, and there were more (which I hope people unfold to us here in this discussion). And now I am thinking that because DiCamillo is not a heavy-handed writer (trying to declare controversial philosophies to the world via messages through her texts), that it could be really interesting to think about the statement in the context of the story. What did it mean—from not only the fortune teller but also the singer (I believe it was)—that the refrain that “the truth is forever changing” was repeated?

I mean, what was its import especially for the main characters: for Peter, for the magician, for the policeman and his wife, for Adele? One could also ask what it meant for the sculptor who could sculpt no more, the dog who was now useless for delivering messages, the beggar whose life was invisible, the washed-up general, for the newly-crippled noble woman.

And I like the note, from LW, about people’s truths (their life situations, their ways of being, their desires and actions) in conflict. This feels like a really big part of the story to me.

Will Willingham says

It was indeed one of the biggest parts of this story to me, of how multiple things, that seem to be in conflict, can be true at the same time, the most obvious being the appearance of the elephant being good (for the magician — it’s such a remarkable feat!) and bad (for the magician — it landed him in jail!) and also bad (for the elephant — she’s been painfully displaced!) and good (for Peter and Adele — the elephant will bring them together!) and bad (for the noblewoman — she’s been injured!). Good and bad and bad and good and bad again, all at the same time.

This is life. At least for me. Learning to hold these things in tension.

I do believe there are truths that do not change. And then there are those that do. And then there are those that haven’t changed but appear to (or, our perception of truth has changed). And there we go again. Multiple true things that coexist. This is the way I read “the truth is forever changing.” 🙂

Megan Willome says

LW, what you’ve written here and above is helping me see why the book left me feeling so uncomfortable. It’s this “bothness” of the story, that more than one thing is true at once and that those things are both good and bad simultaneously.

That is a different message than the kind usually found in fairy tales, and I consider this a modern fairy tale. It’s also a very adult message, which is unusual to find in a children’s story.

Will Willingham says

It’s hard to hold that tension, Megan. And yet I find it to be the way so much of our lives are, hanging in that tension of both-true. Do you find that discomfort you’re feeling as you read to be something you can live with, or something you want to make go away (much like an elephant 😉 ?

DiCamillo is pretty masterful at weaving in the adult story. 🙂

Megan Willome says

I’m used to the discomfort. 🙂

I just find it an unusual–and rather bold–choice for a middle grade novel.

L.L. Barkat says

The girls and I are now having a rousing discussion about the truth and the Truth. Well, it’s beyond the scope of this discussion, for now. But it also made me go back to the book, and I read them the first chapter, and here are some interesting further notes about truth, that I suppose are key both for children coming-of-age and adults like Vilna Lutz who have carefully constructed their lives around certain truths. Let us make of these sections what we will. I think they are intriguing to consider:

-Peter spends a coin that does not belong to him, to learn the truth. This is, in his own mind and in Vilna Lutz’s mind, a wrong thing to do, but Peter hopes to make it at least partly honorable by telling the truth about what he did

-Peter has one question, about whether or not his sister lives, but he manages to get two questions answered by how he handles the situation (the second question being how to find her), therefore skirting the fortune teller’s rule that she will only answer one question for one florit

-“There are no elephants here,” says Peter, when he learns that he must follow an elephant to find Adele. “That is surely the truth, at least for now…” notes the fortune teller.

-Peter has trouble believing that Vilna Lutz could be the one who lies, because, “it was not at all an honorable thing for a soldier, a superior officer to lie. Surely, Vilna Lutz would not lie. Surely he would not. / Would he?”

-“‘I hope that he lies,’ said Peter aloud to the darkness. / And his heart, startled at such treachery, astonished at the voicing aloud of such an unsoldierly sentiment, thumped again, much harder this time.”

I also find it interesting that the final image of chapter 1 is of the elephant attached to a rod in the earth. It’s the classic image of a glorious beast accepting confinement it need not accept, because it doesn’t understand the truth: it could break the chain (in fact, it broke a whole opera roof already, but it does not see the similarity and it does not even try to take action).

Donna Falcone says

I hadn’t caught that! Yes, he got two answers for the price of one question! Clever!

I love this moment: -“‘I hope that he lies,’ said Peter aloud to the darkness. / And his heart, startled at such treachery, astonished at the voicing aloud of such an unsoldierly sentiment, thumped again, much harder this time.”

It’s so important in life to face that side of ourselves we would much rather believe would ever do anything like that – the one who would spend someone else’s money at a fortune teller’s booth (no matter how important the question – ahhh) and the kind of honest person who is wishing for another to lie – not only because the lie would be easier to live with, but also so that the other will have committed the worst offense. Surely using a coin isn’t worse than what a soldier must be ready to do every day – kill – and how much worse is a lying killer than a little boy foolishly (?) spending a coin that didn’t belong to him?

Life can make us squirmy, and this kind of squirmy is necessary. Judith Viorst would call it a necessary loss – the loss of the illusion that we would always walk on this side of virtue (as per social standards) no matter what is at stake.

But, as I mentioned below to LW, I don’t think he would have been satisfied with the lie anyway. 😉 I think he wouldn’t have believed him once it sat in his head for a while.

That is really interesting – that the elephant was so easily held, in spite of all his strength. Hmmm.

Donna Falcone says

Unless the elephant thought she had been stuck in one of those dreams where you can’t run or scream or save yourself… and she just let it roll on til morning.

Michelle Ortega says

I think what causes some of the tension in the phrase “the truth is always changing” is the nature of the word “truth.” There are indeed facts, concrete events that are “true,” such as “Adele is alive.” But then there is the grey area that is uncovered with the elephant’s “truth” that she was not where she belonged. In her frame of reference, she was not where she belonged, but to the others in the story she was exactly where she belonged to be able to fulfill the fortunetellers prophecy to Peter. Perhaps the elephant’s “truth” is actually a “belief,” and it’s beliefs (shaped by changing circumstances) that are always changing.

I think about this in terms of faith, where the Truth is claimed, but my understanding of Truth has changed as my faith has deepened. Or, beliefs can muddle any of the ongoing polarizing conversations of our culture surrounding religion, politics, the environment, when people are speaking from a personal (or corporate) belief system that to them is “truth.”

Will Willingham says

And even that’s a part of the tension, right? It can be hard to say that there’s more than one way to look at “truth,” rather than accepting that both of these things about truth can be true at once. 🙂

I agree our understanding of truth, even of Truth, changes over time, even if the underlying truth (or Truth) does not.

L.L. Barkat says

Something I really love about DiCamillo’s playing with this issue of truth is how the various characters change in the face of new truths. Many of them simply accept the new truth as something that will forever define them (the dog, the sculptor, the elephant). There is resignation. After all, especially in the cases of the injuries, there is no revoking them. The truth is that the sculptor will always be bent, and Madame LaVaughn and the dog will always be invalids in their respective ways.

And I think that’s why Leo’s question “What if?” and Madame LaVaughn’s assistant’s insistence that the magician and ML stop repeating the same truths over and over without modification are so important. Because one truth need not predict another. The sculptor finally creating again is such a picture of this. But we, like the elephant, often hold only one truth in mind at a time, and we let it become the overarching truth that determines all else.

Also, regarding whether we become defined by a truth, to the exclusion of other possibilities, is, at least in this book, related to the issue of love and maybe also vision. And for that, we tend to need others. Again, that was the travesty of the magician and ML’s conversations. They were only Other to each other and not the needed-other. Which left them literally and figuratively imprisoned.

Donna Falcone says

I was struck, immediately, by Peter’s apprehension in asking a question – seeking a particular truth – because what if the answer was no? His sister would be gone forever… somehow MORE gone than she was before he asked. And, what if the answer was yes? There would be a lot to reconcile – how would he find her? What to do about the lies he’s been told? And what would that mean for his only stability in this world, albeit a loveless existence. Stale bread and tiny fishes might be better than nothing.

And so, for me, the courage he possessed in asking the question is his personal, deep truth. His courage wasn’t found in soldier training. He had it all along. We know he had courage because of how afraid he was to ask a question he asked anyway.

The truth is always changing, but only if we ask questions which might even be terrifying, and we in that moment are willing to put our entire foundation at risk, because there comes a time when knowing an answer matters more than what we risk to find it.

I was also very curious about the relapsing fever of Vilna Lutz. I need to think about this some more, though.

Donna says

🙂

Will Willingham says

It’s true, Donna, asking certain questions requires great courage. What a great thing to observe about Peter. 🙂 And it takes great courage for us to ask certain questions as well, because the answers may change what we understand to be truth.

Because if we’re going to read the line literally (not like I’ve done above in reading “the truth is forever changing” to mean that more than one thing is true at the same time), then is it the truth that’s forever changing, or is it that our understanding is forever changing? 🙂

I see that courage as Peter debates back and forth (as Laura notices above) with the “I hope he lies” inner dialogue. When would we ever want someone to be lying? (We would prefer someone lie, even if we hate lying, when we desperately need the truth to be something else.)

Donna Falcone says

Ah, yes, sweet Peter. He was really in a quandary. That would have been an interesting turn – had Vilna Lutz lied and told him what would have been easier, I mean. I have a feeling that Peter would have not believed him, though… not for long, anyway. A person who is moved to ask such a big question will not feel satisfied by the conflict between the fortune teller and Vilna Lutz.

I’m still pondering that fever. I had hatched a theory that two things would happen and I was wrong on both counts. I thought the fevers would stop when Peter and his sister were reunited, and I thought that the woman who was injured would be restored to health once the elephant went back. But the consequences of lies cannot be so easily reversed… not even in this fairy tale. Adele did offer compassion and care to Vilna Lutz, however, which I find really interesting. Maybe because she was less tortured by the lie. She hadn’t been tricked into breaking a promise to a dying mother, and so maybe it was easier for her to help him in his time of need. Although she was in an orphanage, she was also with a woman who cared for her and probably even loved her – a woman who understood light – and so Adele possibly saw the light in poor Vilna Lutz. Peter, on the other hand… his wounds were different, and very deep.

This was a great pick for book club!

Donna Falcone says

Only maybe I was right about Madam LaVaughn. When a great weight flapped free of her – do you think she could walk, again?

I love how it ends with forgiving – I could like snow again, briefly, for this. 😉

Will Willingham says

I don’t get the idea that she was able to walk again. This is something that DiCamillo does quite well, creating endings that are not quite “happy.” There are happy parts, yes — the home that welcomed Peter and Adele, the elephant’s return home, the magician’s new life. But nothing changes for Vilna Lutz (one could argue his life is worse, as he no longer has the constant companionship of Peter and a sense of purpose in training him to be a good soldier, even if he does now have the visits from Adele), and the noblewoman’s injuries were real, not mere figments created by her grief and anger, and they did not, as best as I can tell, go away when the magician undid his magic.

I typically find myself at the end of a DiCamillo story in that place of being deeply disappointed (over the lack of the happy ending I was angling for — case in point, read Edward Tulane, oh my) and being fully content. Again, it’s the two truths existing alongside one another: I am disappointed because I am wishing, yet content because it is, after all, the way life works. And she paints these endings where even though things don’t turn out as we might wish, it’s evident that the people are going to be okay. So then, contentment. 🙂

Donna Falcone says

Yes. Contentment. I felt that way at the end. 🙂

I never thought her injuries were not real. I just hoped that by returning the elephant via magic, the damage done to her would be reversed (which I guess would not make sense… of course now that I think of it, because to reverse the things that happened, along with sending the elephant back, would mean to separate Peter and Adele again. Sigh. But still, I do get the feeling they are all okay, and even Vilna Lutz might in the end be better off – because in my mind the story goes on like a dream you keep creating after it is over – Adele cares for him and by her example the others soften, offer him kindness, and maybe even stew. Not right away, but eventually. You know, forgiving snow and all.

Christine Guzman says

I haven’t read this book, but reading all your discussions – seems a very similar read in Jodi Picoult’s book: Time Flight – about an elephant researcher’s daughter who goes looks for her missing Mother. It involves a retired detective and a fortune teller, both flawed individuals who have made mistakes in life.

A very fascinating read, giving lots of information on elephants and their human caretakers behavior, the “truth” of the book takes a very unexpected turn at the end.

Terri says

This may be over-spiritualizing the story, but I see themes of the spiritual movements of desolation (a period of feeling abandoned, crying out for God to reveal himself) and consolation (the comfort that follows desolation, which often reveals deeper truths about oneself, or about God.) By that, I’m not implying that it was Kate DiCamillo’s intent, only that the movements are very much a part of our human experience on earth, and that DiCamillo is a truth-revealing author.

I love all the insights y’all have brought to light about this deep little book. Brilliant. DiCamillo is amazing.