Ruins are my weakness. Witnessing the remains of former dwellings unnerves me—especially when the site’s abandonment remains unexplained. Wistful over what has been irreparably lost, I’m also intrigued. Curious.

My husband and I have been seeing America via Big Ed, our 30’ RV—a far cry from our backpacking days. I’ll just say this: A girl my age craves a few amenities. We hope to see all the National Parks before we’re reduced to pushing up daisies.

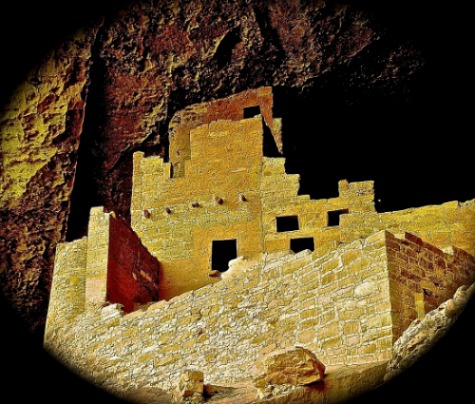

Recently, we visited Mesa Verde National Park, in Colorado, home of the fabulous cliff dwellings. It’s also our only National Park dedicated to a culture. The region is one of North America’s premier expressions of human culture.

Ruins at Mesa Verde National Park in Colorado

Our first morning there, we scanned the park literature, which mentioned more than 4, 000 archaeological sites and over 600 cliff dwellings, some more accessible than others. My husband wanted to see Balcony House, the most athletic tour. Allergic to heights, I half-dreaded the day. Ancient Mesa Verdeans were resilient. Courageous. I hoped I would be, too.

They were also artistic and highly organized. Formerly called the Anasazi, their current name, Ancestral Puebloans, was given to honor their link with modern descendants. Between 1150 and 1300 A.D., their civilization flourished. Alongside ingenious buildings and irrigation systems, Ancestral Puebloans accomplished something revolutionary.

Something scholars have failed to completely explain.

Something I would fail to appreciate until later that day.

Don’t look down

More than 700 years ago, Balcony House, which faces east, was built on a high ledge. A stone honeycomb of 45 rooms, it’s a multi-storied ruin.

I’d been warned that I’d have to descend a 100-foot staircase, scale a primitive 32-foot ladder, squeeze through a 12-foot tunnel the width of a chair seat, climb two more ladders, then switch-backing flights of uneven steps carved in stone—with only a chain for a handrail.

Stone steps with chain handrail

Stone steps, another view by Jirka Matousek

Was I ready for this?

Before our tour group faced The Gigantic Ladder of Death, the ranger encouraged each of us to make the wisest choice for ourselves: a quiet “out” with honor.

I was tempted.

Ladder of Death

When a woman twenty years older than I opted for the climb, my pride kicked in. Tuning out the ranger, my husband, the waiting crowd, I white-knuckled up that ladder as fast as I could, mentally chanting Not a wuss, notta-wuss, not – a – wussss.

Safely inside the ruins, we learned Ancestral Puebloans had used only hand-chiseled toeholds. Babies bound to their backs and crop baskets cinched with straps around their foreheads, adults spidered down open rock face, from mesa to canyon floor.

“The Ancient Ones, ” Edward J. Fraughton, Cast Bronze, 2012

Mortared blocks of sandstone resembling loaves of bread still stoutly enclosed the communal storehouse. Masonry crenellated by time partially defined former apartments. Remnants of painted walls suggested personalized décor.

Prehistoric color schemes? I loved these people.

Bemused, and slightly chilled, I ambled through haphazard shadows, quietly slipped into rooms formerly enlivened by men and women with shockingly brief life spans (35-40 years)—so arduous was their survival.

Metates, or stones for grinding corn, ranged across a flat rock, as if the women had just stepped out (or up) for some sunshine.

Metates

Everywhere I looked hints of once-vibrant community permeated the atmosphere. I filled in the emptiness by conjuring aromas of baking squash and beans, an echo of footsteps. I could almost hear songs and stories shared around fires, as wind honed itself like a blade against the stone.

I was eavesdropping on absence.

Pulling my jacket closer around my body, I wondered why intrepid people would abandon their state-of-the-art homes.

In the presence of death or unexplained endings we often shiver. I did. Mortality jars us, like missing that last rung on the ladder. How will we manage the cumulative wear of time?

Geographically speaking

My husband majored in Geography. Mesa Verde is Spanish for “green table”—a geographical misnomer. A mesa is flat. Mesa Verde is a ridge that slants to the south, steeply on one side, gently on the other. The correct term is cuesta.

“Slant” is one reason deep alcoves formed in Mesa Verde’s towering canyon walls. (An ancient sea, cycles of drought, uplift and subsequent erosion played additional roles.)

Imagine living within a vast, echoing bowl of stone, tipped up on its side.

More mystery

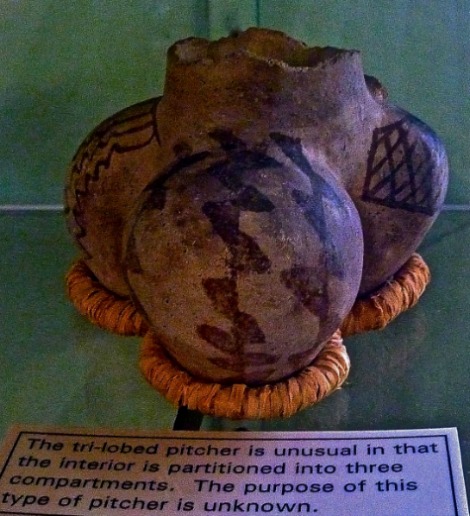

In the visitor’s center we cruised the exhibits. I pored over pottery from the area’s golden age.

To this day, people of the Southwestern pueblos believe their vessels embody Spirit. Born of Mother Earth’s body and bounty—from various clays to plants used for brushes and pigments—hand-built vessels are every-day-sacred objects. They emanate mystery.

Who taught the Ancestral Puebloans how to make pottery? Early Mesoamericans?

The Mogollon people lived nearby. Did Ancestral Puebloans buy pots from them, then copy their work?

Here’s my favorite theory: Perhaps an enterprising woman lined a cooking basket with mud to create a better surface for parching seeds. Perhaps the basket caught fire, then burned away, leaving behind the fired clay: voila, her community’s first bowl.

No one knows their pottery’s origins, just as no one knows why the people left.

By now, my husband had left. He needed fresh air. I couldn’t stop reading. Early pottery attempts probably used the bottoms of baskets as molds. Additional coils of clay created each vessel’s height.

Trial and error taught rookie potters the clay would crack unless bonded with another substance. Not grass. Not straw. These burned out during firing, leaving holes in the pots. Mixing in local volcanic ash finally solved the problem.

I thought of the Mt. St. Helens eruption, all the souvenir pottery made from its ash still for sale, resourceful people re-shaping catastrophe into a new means for living.

I thought about blending various elements in poems, and essays, sealing the gaps in logic, creating an argument that holds water.

Trial and error and perseverance, using what’s at hand. What’s in the heart.

The revolutionary part

Some scholars believe women became the community potters, passing down tools and skills from mother to daughter. Seed jars, cooking pots, ladles and pitchers, canteens and water jars, spectacular mugs and bowls—over time, their repertoire expanded.

No more dependence on leaky baskets or drawstring pouches made of animal hide. Mole- and rodent-proof, fire- and bug-proof, heavier than baskets, yes, but waterproof—pottery revolutionized women’s lives.

No more nomadic sojourns. Pottery clinched settling down. Farming and architecture developed.

Pottery ushered in leisure. More efficient food storage and preparation allowed time for artistry to grow.

• Stunning black-on-white geometric designs developed

• Red ochre pigment soon enhanced ornamentation

• Individual styles, shapes, and symbols emerged

Then, as now, a bowl was for holding, a classic ceramic embrace. Shallow or capacious, crimped or wide-mouthed as the proverbial frog, a bowl’s open posture invited response.

What was I holding forth in the world? Something within me hungered for hands-on connection. For newness amid antiquity.

I bought a DIY pottery kit.

The Dreaded Ping

The kit supplied dark, stiff clay. Once we were home again, a little water and persistent kneading softened my lump. Eventually.

Ancestral Puebloans would have prayed, then gathered clay from a pit or mine, filling a basket, which they hefted up those perilous toeholds.

“We’ve come a long way, ” I told my husband while pummeling my clay.

Thanks to modern neutron activation analysis as well as contemporary wares made by Puebloan descendants, experts can infer how early pots were made.

• Clay was pulverized, then soaked for a week to remove impurities.

• Volcanic ash tempered clay against the firing’s thermal shock.

• Warning! Flawless consistency was crucial. A single impurity would cause a small pock, or ping, in the clay, cracking the vessel—even years after completion.

• Readied clay was rolled, coiled, molded, or pinched into shape.

• Once dried, vessels were scraped smooth with a piece of gourd, then burnished with water and a polishing stone. Over and over.

• Slip, or very thin clay (up to 8 coats), was applied.

• More drying.

• Designs were incised.

• Pigments were mixed from ground minerals and vegetation, then applied with strips of yucca, chewed at one end to form a brush.

I dutifully chewed my yucca. It did not taste like chicken.

Fire and dung

My bowl air-dried on our counter. No rituals. No special conditions.

For the Ancestral Puebloans, a windless day, warm ground, and prayers accompanied the firing process. Lacking kilns, workers amassed cracked pots—their ruins a subtle message, perhaps? Careful hands balanced the new pots atop the rubble, piled on more sherds, then lots of dried dung.

Then another layer of finished pots. More sherds. More dung. Tinder, tented around the mound’s base, was ceremoniously lit. Firing took all day.

Unearthed, the cooled pots, when sharply tapped, rang like crystal.

Post-ruins

After conquering the giant ladder to experience the ruins at Mesa Verde, after researching its pottery, and after shaping and painting my own stubborn lump of clay, I feel hollowed out. A little haunted. Ready for something to grow.

“Your bowl looks authentic, ” my husband says. We can’t identify the traditional “water animal.” An arthritic reindeer with an overbite?

My odd little bowl embodies generations of souls linked by earth and need and the love of beauty. Dust to dust. Ashes to ashes. An ongoing hum of the same crystalline song.

Featured image by David Fulmer. Stone steps photo by Jirka Matousek. Both Creative Commons license via Flickr. Post by Laurie Klein, author of Where the Sky Opens. Post photography by Laurie Klein. Used with permission.

Sources Consulted

National Park Service

Ancestral Puebloans, Rose Houk, Western National Parks Association, 1992, pp10-12.

Pueblo Pottery Kit, Lorna Pollock, Wildwoods Crafts Lot. Mariposa, CA

Wikipedia

Cameron Trading Post

Sophie Wagner-Marx, Waunakee Community School District

Women Artists of the American West

Mesa Verde visitor center displays

Coffee Times

Browse more Regional Tours

Read our interview series with Colorado Poet Laureate Joseph Hutchison

Enjoy a Mischief Cafe in Colorado Springs

__________________________

Megan Willome’s The Joy of Poetry—part memoir, part poetry reflections, part anthology—takes readers on a journey to discovering poetry’s purpose, which is, delightfully, nothing. “Why poetry?” Willome asks. “You might as well ask, why chocolate?” Poetry reflects nothing more and nothing less than the pure joy of living, loving, and being, in all of its confusion and wonder. Willome’s book will gently guide you to read, write, and be a little more human through language’s mystery and joy.

—Tania Runyan, author of How to Read a Poem: Based on the Billy Collins Poem “Introduction to Poetry”

- Poems to Listen By: Yondering—6: Restricted Travel - March 26, 2025

- Poems to Listen By: Yondering—5: Upon Arrival - March 12, 2025

- Poems to Listen By: Yondering—4: Off the Map - February 19, 2025

Sandra Heska King says

My husband and I visited here 30-something years ago. We loved it. But I don’t remember that ladder. I didn’t make any pottery. We must have missed a lot. Thanks for catching us up.

I stopped and read this line several times: “I was eavesdropping on absence.”

Your words reminded me of a poem I wrote a few years back. I hope it’s okay to share it here.

Bring Me That Piece of Pottery

“Bring me that piece of pottery,

the one that feels like poetry.”

Whispered words slipped

from lips dry like sun-cracked earth,

thirsting now to touch the flow

of lines and patterns in polished clay

thrown and balanced on earth’s wheel

brushing fingertips of soul,

an Adam vessel smooth and cool

now centered on the stage

as curtain draws a final bow.

The spirit spins complete

and snaps the golden thread

to sing eternally.

(“Bring me that piece of pottery, the one that feels like poetry” was something my husband’s actor cousin requested when he was dying from cancer.)

Laurie Klein says

Sandra, what a marvelous poem you’ve written from that poignant, remembered quote, spoken aloud by family from the rim of eternity. A breathtaking way to start my day. Thank you.

Maureen says

One of my favorite parks. It’s such a fascinating place to spend time. I do remember doing a lot of climbing. Getting through some of the passageways can be difficult, even for a person as small as I am. It was thrilling.

Thank you, Laurie, for taking me on your tour.

Laurie Klein says

Maureen, “fascinating” and “thrilling” are perfect words to describe Mesa Verde. I wish we’d had more time to spend there, although one trip up that giant ladder was enough for me. 🙂

I wondered if I’d get claustrophobic in the tunnel but managed it by focusing on the glimpse of daylight. I lost my sunglasses en route and crawled right over them. Thankfully, the person behind me rescued them before they were shattered.

Glad to know we share the wonder of this singular place!

Megan Willome says

Laurie, this is wonderful! I’ve never been, but my husband went many times growing up–multiple home movies of the family at Mesa Verde. You’ve helped me understand why they continued to return to that place.

P.S. Go NPS! One of the best things about our country.

Laurie Klein says

Megan, so delighted to give you a cyber-tour! Rich memories for your husband and family. And yes, here’s to the National Parks!!

Bethany says

What a beautiful post, Laurie. I have to admit I started to feel a bit woozey just looking at that picture of the chain handrail — what a feat to have climbed there. And what a rich experience you’ve come away with. Thank you for sharing it with us.

Laurie Klein says

Bethany, there were woozy moments for me, too. I have always admired intrepid travel writers and what they will risk for the experience and the story. In my case, I learned a little more about myself and ways to manage my fear as well as geology and amazing people and art forms and times. Feeling richer for it. Thanks for your encouragement!

Donna Falcone says

Wow Laurie! Thank you for this! You have taken me back to something I actuallly did as a child – I visited Mesa Verde – we walked around in the places they allowed tourists and we peered up at the toe holes wondering how they did it without all the ladders and handrails and …. and… you know I can’t for the life of me remember how we got UP (or down) into the Mesa we visited – did I walk that same trail you and your husband walked, fifty years ago? You’d think a kid would never forget that kind of experience, right? So maybe I didn’t, but then how did we get there? We have pictures – I was there. Now you have me wondering how I got there, and how a thing like this can be forgotten.

I love your way of telling this story – the reverence… the humor… the history and the present so richly interwoven. I can’t get over this wonderful short sentence: “I was eavesdropping on absence.” Just, oh.

laurie Klein says

Donna, hello my friend! I bet you were fearless and captivated, so no drama about getting up and around the fabulous ruins. Thanks much for your encouraging words. Love knowing the piece took you back and stirred you too!

April Yamasaki says

Laurie, it’s such a treat to read your wonderful post. I’ve never been to Mesa Verde and perhaps never will, but I’m living it vicariously through your thoughtful words and pictures. I’m glad that you were “eavesdropping on absence,” and thank you for sharing your travels

Laurie says

April, I am delighted to give you a virtual tour! Thanks for traveling along. I know your time is precious.

Pat Foster says

Hi Laurie,

You have such a wonderful gift of expression, in your writing as well as your music. My first job out of college was Ranger Archaeologist at Wapatki National Monument, near Flagstaff, AZ. This was another site the Anasazi left. We don’t know why. I often had the same feeling walking through the ruins. How would it be to have lived then? Why did they leave? This Spring I toured an ancient Celtic ruin in Spain. This dated back to 2000 BC. These were circular stone dwellings honey combed on the top of a mountain. I had the same feeling wandering through these. Your article really spoke to me.

Laurie Klein says

Pat, what a cool job to have on your resume. I never knew about your work there. Your time in Spain must have been wonderful. The mystery of abandoned ruins reminds me what the word awesome really means. Makes me want to move on tiptoe.