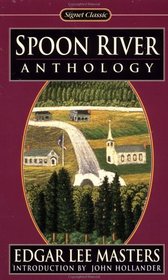

If you asked who my favorite poet is, I wouldn’t hesitate in my answer: T.S. Eliot. If you asked me my favorite poem or collection of poems, my answer would not be “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock” or “The Hollow Men” or “Four Quartets.” My answer would be Spoon River Anthology by Edgar Lee Masters (1868-1950).

I first read Spoon River Anthology in high school, junior year, in fact, the year we all took American literature (paired with American history). Our teacher, Mrs. Prince, was a larger-than-life character who spoke in breathless superlatives and occasional exuberant shouts. She told us that Jacqueline Susann’s Valley of the Dolls was the greatest American novel ever written; it had been published the previous year.

She loved American literature, however, and she was wildly enthusiastic about Huckleberry Finn (apparently is was almost as good as Valley of the Dolls) and Walt Whitman. But when she introduced us to the Realists (Edith Wharton, Jack London, Willa Cather) and the early Modernist poets (Eliot, Vachel Lindsay, Sara Teasdale, and others), I believe I fell in love with literature.

We read parts of Spoon River Anthology, that collection of more than 200 tombstone inscriptions, aloud in class. I read the whole work for a research paper. I was enthralled. The class even attended a production of Thornton Wilder’s Our Town, which seemed to me a dramatic version of Spoon River Anthology.

The Edgar Lee Masters Home in Lewiston, Illinois

Masters was born in Kansas but moved at a young age with his family to Lewiston, Illinois, whose Oak Hill Cemetery furnished the setting for the poems. His love was literature and poetry, but he trained as a lawyer, and moved to Chicago to practice. For several years he was the law partner of Clarence Darrow. He published a few collections but without much notice or success. In 1914, Marion Reedy, editor of Reedy’s Mirror in St. Louis (and a promoter of Carl Sandburg and Sara Teasdale, among others), published several of Masters’ poems, which were noticed by Harriet Monroe of Poetry Magazine. She helped Masters assemble the collection that became Spoon River Anthology. It was an almost overnight sensation and national bestseller.

What it did was simple. At a time of industrialization and burgeoning growth of the cities, it reminded people that their romantic notions of small-town life were more nostalgia than reality.

I reread the work in the early 1990s, about 25 years after first reading it. I was still fascinated by the picture it painted, the stories it told, and the concise way it told those stories, so that a few short lines of verse unfolded a person’s life.

Edgar Lee Masters

And a few weeks ago came my third reading. What strikes me forcefully now that didn’t strike me as much in the two previous readings is how dark the work is. The stories told by the tombstone inscriptions are largely stories of sin, failure, crime, and the sense of profound loss. A few are positive, but most of the poems are about untimely death, lost love, murder, industrial and work fatalities, political corruption; hypocritical ministers, women who die having abortions and the doctors who perform them, unhappy marriages, and general misery.

What also strikes me is the connections between groups of poems, so that we see the same events through different, often completely different, perspectives. Overall, the poems offer a dark view of small-town life, and a dark view of humanity.

Here is one I missed, or didn’t remember, from the first two readings, the one that might summarize Masters’ own experience as a poet.

Petit, the Poet

Tick, tick, tick, like mites in a quarrel—

Faint iambics that the full breeze wakens—

But the pine tree makes a symphony thereof.

Triolets, villanelles, rondels, rondeaus,

Ballades by the score with the same old thought:

The snows and the roses of yesterday are vanished;

And what is love but a rose that fades?

Life all around me here in the village:

Tragedy, comedy, valor and truth,

Courage, constancy, heroism, failure—

All in the loom, and oh what patterns!

Woodlands, meadows, streams and rivers—

Blind to all of it all my life long.

Triolets, villanelles, rondels, rondeaus,

Seeds in a dry pod, tick, tick, tick,

Tick, tick, tick, what little iambics,

While Homer and Whitman roared in the pines?

Masters would eventually give up his law practice and move to New York City to write full time. He wrote more poetry, an autobiography, and non-fiction works, but never again achieved the fame he gained with Spoon River Anthology. Still, to have achieved what he did with this work was sufficient enough. More than a hundred years later, it still speaks to us of the human condition.

Related:

Spoon River Anthropology: Tracking the Ghosts of Edgar Lee Masters

Photo by Pai Shih, Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post by Glynn Young, author of the novels Dancing Priest and A Light Shining, and Poetry at Work.

__________________________

“I require all our incoming poetry students—in the MFA I direct—to buy and read this book.”

—Jeanetta Calhoun Mish

- Poets and Poems: Sandra Marchetti and “Diorama” - April 24, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Christina Cook and “Roaming the Labyrinth” - April 22, 2025

- Longfellow’s “Paul Revere’s Ride”: Creating a National Legend - April 17, 2025

Rick Maxson says

Thank you for this essay, Glynn. We ran the poem for “Isaiah Beethoven” not to long ago in EDP and that was my first rereading since high school. When I was younger, I remember dismissing Spoon River Anthology as simple. I thought of Frost the same way until much later in life. My loss. I love the example you extracted. What description in the last 7 lines!

Cinematically, today we have the equivalent in Twin Peaks and Blue Velvet. But I have sought small towns all my life. If I’m going to have drama and angst around me, I want a mill wheel and pond available to ruminate about it, a wood nearby to restore my sight and hearing.

Bethany says

I enjoyed hearing your take on the Spoon River Anthology the third time through. Isn’t it interesting how varied our own takeaway can be about one work after multiple readings? And over time?

Sandra Heska King says

I don’t remember ever reading Spoon River Anthology. I don’t remember much of what we read in high school literature class. When I read your pieces, I feel like I’m finally learning a lot of what I missed–or forgot. Even though English and lit were my favorite classes, I think I tried too hard then to “get it right.” I don’t think I enjoyed it as much as I could have–and certainly not as much as now.

Megan Willome says

Glynn, it is three years after you wrote this, but I’d tucked it away. I just started reading “Spoon River Anthology,” and I’m enthralled. Like you, I love the different perspectives of the same people and events.

What puzzles me is where did this nostalgia for small-town life originate? It never has been idyllic. It isn’t now, and it won’t ever be. Why then do we perpetuate the myth?

(Speaking as someone who lives in a small town and loves it, but with wide-open eyes.)

Glynn says

Megan, I’m impressed you kept this for three years!

I suspect nostalgia for small-town life goes back to the 19th century, as the US was industrializing and people were leaving the farms for the cities. Life seems simpler in small towns, although I suspect that the reality is that the complexities are there in small-town life but different from those in the cities.

The smallest town I ever lived in was 120,000 people, so I can’t say I have vast experience in living in and understanding small towns.