It happened, therefore it can happen again: this is the core of what we have to say. It can happen, and it can happen everywhere.” ~ Primo Levi

A renovated boxcar is set on rails embedded in the floor where we enter the Holocaust Memorial Center. Two hundred people might have once crammed inside to start a three- to six-day journey in stifling heat or freezing cold. They may have anticipated resettlement somewhere, unaware they were about to lose their names and identities, that they’d become mere numbers, that these days could be their last. Or since they had friends or family they’d never heard from, maybe some did suspect.

Nobody knows for sure if this particular car was once packed with Jews, but it’s one of the last existing World War II-era German boxcars. It’s the same type the Nazis used. I linger alone, tiptoe around it, dare to reach out and touch it, feel the lock, stroke the door and walls. My eyes well. I’m barely breathing.

Our next stop is in the circular room that displays a timeline of Jewish history, beginning with Abraham’s migration from Haran to Canaan, juxtaposed with milestones in world history in a way that hints that the world fiddled while the Jews burned. Of course, how could the world know the extent of the extermination when the news was buried in the papers? We later learn that The New York Times published a full-page apology on November 14, 2001.

A picture is captioned: “Hank Greenberg leads Detroit Tigers to 4 World Series (1934-1945).” On the same line I read that the Nuremberg laws were imposed against the Jews in Nazi Germany.

When I get home I do a little research and learn that Greenberg was “one of the most famous Jewish American baseball players of all time.” He closed the 1938 season on October 2 three home runs shy of beating Babe Ruth’s record of 60, in part because pitchers walked him during the last five games instead of letting him hit. I would have been in the stands cheering wildly.

Three days later, Germany required all Jewish passports to be stamped with a “J.” And a month later, November 9-10, Kristallnacht (The Night of Broken Glass), became a turning point in the Nazi’s attempt to annihilate the Jews.

In the United States, Crystal Bird Fauset became the first African-American female state legislator, elected on November 8 in Pennsylvania. On November 10, Kate Smith sang “God Bless America” for the first time on her weekly radio show, and Pearl Buck received a Nobel prize for literature for The Good Earth.

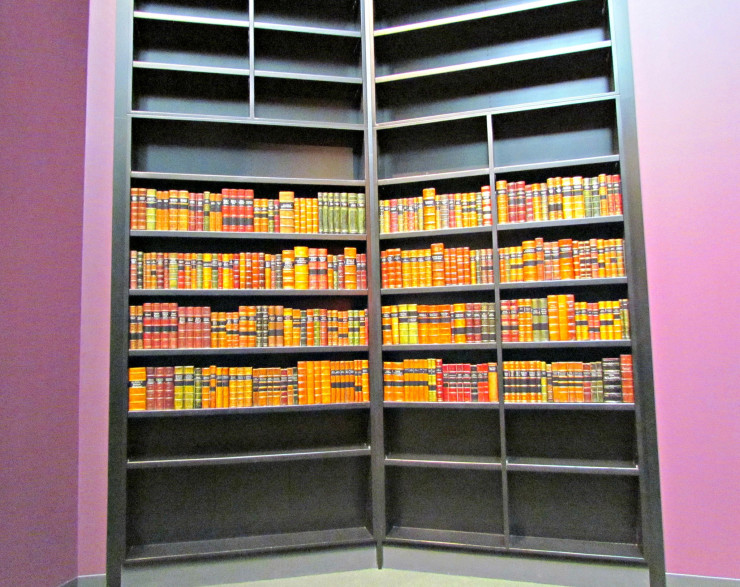

The museum’s Jewish history and cultural exhibit is presented in vivid color, but when we meet up with our guide, he points out how the space moves from open and light to narrow and dark as we approach the large poster of Hitler. We stop before a bookcase, and he points out the center shelves that display images of books written by Jewish authors. The top bookshelves are empty because there’s no way to know what adults might have written. The bottom shelves are also empty. He reminds us that 1.5 million children died during the Holocaust. Who knows what literature they might have contributed. What future Nobel prize winners were exterminated?

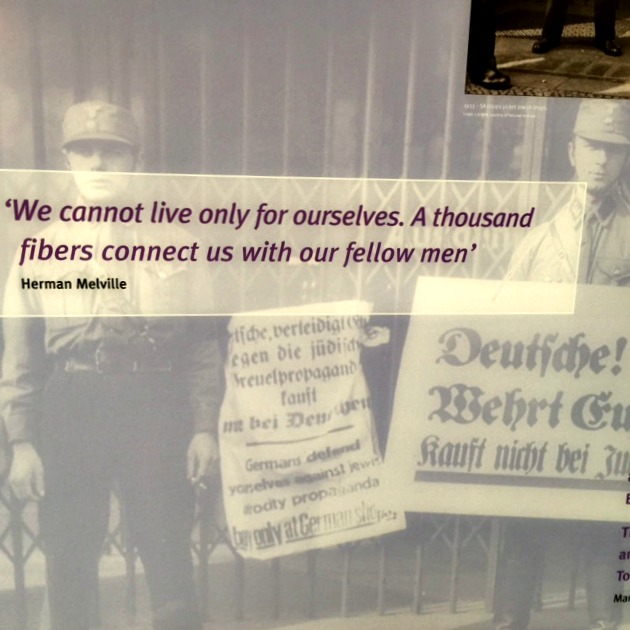

Our guide tells us that 10-12, 000 Jews died fighting for Germany during World War I, and 25-30, 000 Jews were awarded medals. But after the war, Germany’s economy suffered, and as Nazism continued to rise, the Jews became scapegoats. In the early 1930s, they were expelled from professional services. They lost jobs, voting rights and citizenship, and they were forced to wear Star of David patches. The Nazis burned books that weren’t authored by Germans.

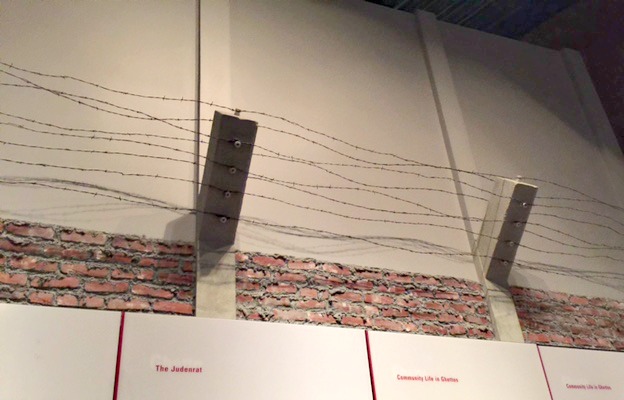

They constructed ghettos to confine Jews. Poland had the largest population (they settled in Poland in 1364 according to the timeline), and those behind the wall in Warsaw tried to establish a normal life, including literary evenings and concerts and clandestine libraries—entertainment to provide diversion from the circumstances. Writers and poets continued to work to keep the heritage alive.

Killing squads systematically murdered those “unworthy of life”—not just Jews, but Jehovah’s Witnesses, homosexuals, gypsies, and those with mental or physical disabilities. The one person/one bullet system was psychologically hard on those asked to pull the triggers, so the Wannsee Conference established the “Final Solution of the Jewish Question”—mass killings by gas instead of guns. It proved more economical and increased deaths from thousands to millions.

Our guide leads us into “The Abyss” where several screens flash images of the “evidence.” He describes this area as depicting the lowest thing people can do to people. These photos and movies are hard to watch. But General Eisenhower required news media and military camera units to record proof of what had happened.

Bright spots in our visit included the “Institute of the Righteous” where we were introduced to many non-Jewish people who stood up and helped, such as Varian Fry, the “American Schindler, ” a journalist and editor who smuggled thousands of refugees—including scientists, musicians, writers and artists—out of France.

Samuel Pruchno’s four paintings portray his experiences during the Holocaust, and I sit with those for awhile. I try to imagine what those Hershey bars the American soldiers threw from the tank during their liberation must have tasted like.

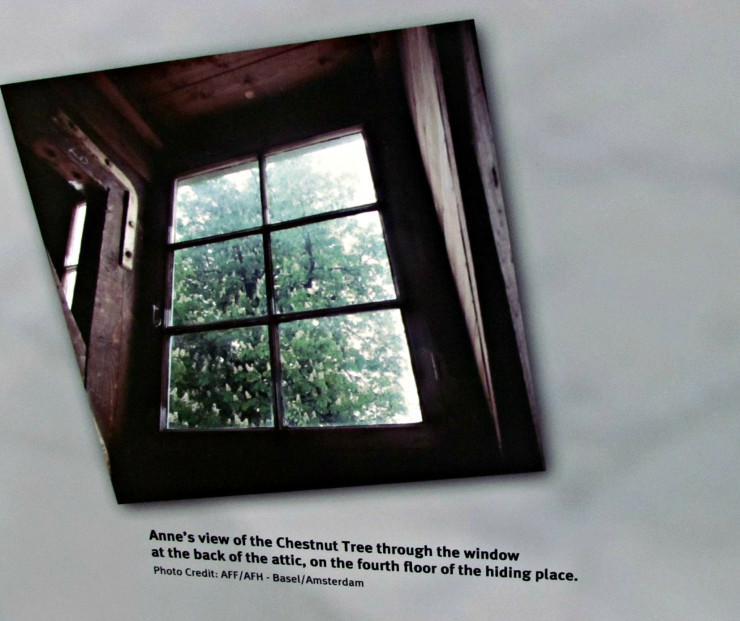

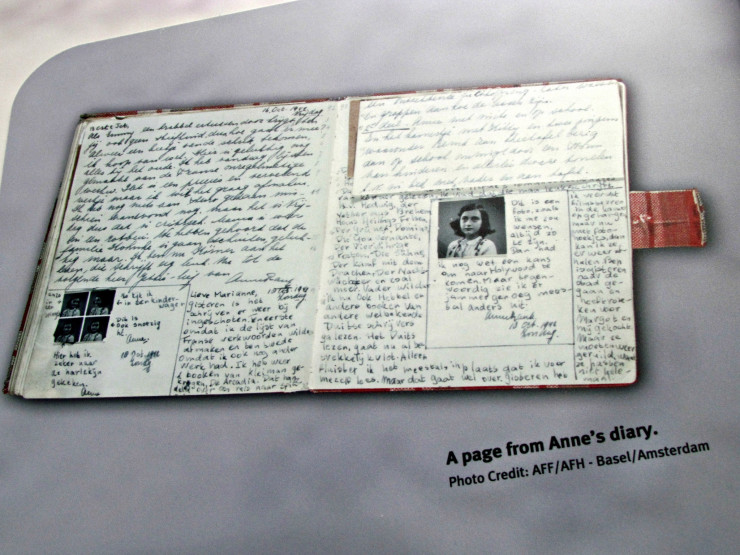

“From my favorite spot on the floor, I look up at the blue sky and the bare chestnut tree on whose branches little raindrops shine, appearing like silver, ” Anne Frank wrote in the Diary of a Young Girl. Watching the tree change through the seasons her family spent in hiding in an attic gave her hope. The Holocaust Memorial Center is one of only eleven sites in the United States to receive a sapling from that tree. I stand at “her” window and imagine hanging hope on a tree.

At the end of our tour, we listen to Fred Findling, a Holocaust survivor, share his story. His given name is “Siegfried, ” which means “dragon slayer.” That name gave him courage, he says. His father was deported to Poland in October 1938 (the same month that Hank Greenberg was trying to beat Babe Ruth’s record). Fred witnessed the torching of a synagogue during Kristallnacht. Through the efforts of Eleanor Roosevelt, he and his brother eventually came to the United States and were placed in an orphanage. He told us how he worked as a “soda jerk” and eventually went to Wayne State University where he ate bread and soup he made from catsup and water. He became an attorney and later in life learned of his parents’ deaths. One third of the world’s Jewish population died, he told us. He’s now 85 years old and says though his brother has not quite overcome the trauma and dwells on the past, he himself lives for the present and the future. He said success is his form of revenge.

“The term genocide did not exist before 1944, ” our guide told us. He talked about the companies and institutions and countries who watched and did nothing. Today someone is a victim of genocide every 19 seconds. He asked us to think about how we might be responsible to help stop it, to think about how we can accept and value differences. He reminded us that we are free to do nothing.

A quote by writer, poet, and Holocaust survivor Primo Levi on the wall in the mock camp reads, “It happened; therefore it can happen again . . . It can happen everywhere.”

Browse more Regional Tours

Explore the Holocaust Poems series with filmmaker Janet R. Kirchheimer

Featured image by Chris Jones, Creative Commons license via Flickr. Post and museum photos by Sandra Heska King.

Click to get 5-Prompt Mini-Series

- 50 States of Generosity: Iowa - April 7, 2025

- 50 States of Generosity: Montana - January 27, 2025

- 50 States of Generosity: Idaho - December 16, 2024

Maureen says

Thank you for this post, Sandra. These centers/museums serve such an important function. We cannot have the luxury of forgetting.

I’m curious: how did the center come to be established in Farmington Hills?

The Holocaust Memorial Museum in D.C. has some of the most moving objects to be found, including a huge wall of images, a boxcar, a mountain of shoes. The architecture of the museum, with its watchtower-like windows, even resembles on the outside a concentration camp. It is not an easy place to visit.

Sandra Heska King says

Maureen, its founder Rabbi Rosenzveig, was a local holocaust survivor who lost his mom and dad and bother and sister. The original museum opened in 1984 and was later moved and expanded in Farmington Hills. I’ve read pieces that said it was the first museum of its kind in the United States, but I haven’t confirmed that.

Some things I’ve read later–and kind of missed on this first visit were more of the metaphors that were utilized in the building–like the elevator tower that resembles smokestacks from the crematoria, the use of sheet metal to resemble the gray and blue uniforms the Jews were required to wear. If I ever go back, or to another one, I’ll pay more attention to that. I’d like to visit the one in Washington–or maybe not. This visit was hard enough. But oh so important to have experienced.

Dolly Lee says

Sandra,

So very important to remember even though it is very hard. Thank you for bearing witness.

Sandra Heska King says

Hard, yes. At one point on our tour, the guide had us step inside another boxcar replica, When we stepped out in front of a “camp,” he divided us up. One group would live. The rest of us (me included) would die immediately. Thanks for reading, Dolly.

Elizabeth says

My daughter visited the concentration camps in Germany last fall. More horrific than you can imagine, she said. Sitting on a flight to New York last summer I met a wonderful Jewish woman. She told me of the loss of family members during the holocaust, and of her fear of the rising anti-semitism in our world.

Sandra Heska King says

I can’t imagine standing on that ground. My sister is the communications director for the Catholic Diocese in my hometown. They’ve sent something like 42 World Youth Day “pilgrims” to Poland. Yesterday (or the day before), they toured Auschwitz-Birkenau. The photos she posted on the diocesan site are pretty sobering

Martha Orlando says

Reading this left me in tears . . . It happened and can happen again. Praying it never will!

Blessings, Sandra!

Sandra Heska King says

Oh, I hope not, Martha. Our guide did point out, though, that someone is a victim an act of genocide every 19 seconds. The term didn’t even exist until 1944. It was coined in response to the Nazi extermination of the Jews. Hugs to you.

Laurie Klein says

Sandra, what a powerful post and group of photos. I saw Dachau some years ago. Haunts me still. Thank you for bringing this to us, “Lest We Forget”

Sandra Heska King says

I can only imagine, Laurie, how moving that visit must have been. Thanks so much for reading and for letting me know you did. This trip left an imprint on me. I won’t forget.