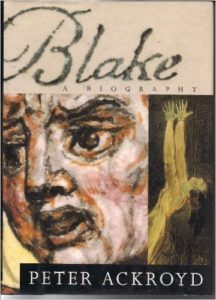

British writer, historian, biographer and novelist Peter Ackroyd, and Harvard professor Leo Damrosch, have both written studies of the poet and artist William Blake (1757-1827). Although the two works are separated by 20 years (Ackroyd’s in 1995 and Damrosch’s in 2015), they form a cohesive understanding of Blake and his work. Damrosch used Ackroyd’s biography in his own research, and calls it one of the best ever written about Blake.

Blake: A Biography is classic Ackroyd, whom we in the United States would call a popular as opposed to academic writer but who occupies a different position in Britain. Amateur historian and biographer he may be, but few living writers today can equal his output, erudition, and insight. He’s in the process of writing a multi-volume history of England. He’s written three novels. He’s retold the stories of the legend of King Arthur and The Canterbury Tales. And he’s written biographies of Charles Dickens, T.S. Eliot, Sir Isaac Newton, Edgar Allen Poe, Geoffrey Chaucer, J.M.W. Turner and Shakespeare. And William Blake.

We see Blake growing up in a “Dissenting” household (people who did not belong to the Church of England). We’re walking with him on a London street when he gets caught up in the anti-Catholic Gordon Riots that led to looting and the destruction of Newgate Prison (nine years before the Bastille was stormed in Paris). We discover that London always seemed like a riot waiting to happen, and that public licentiousness at all class levels was common. We rub shoulders with the artists and poets who were his friends, and those who thought he was more than slightly mad.

This is where Ackroyd excels as a writer, allowing us to imagine what it was like to be William Blake, and how his personal life and the times in which he lived shaped and directed his art and his poetry. Here, for example, is a poem from Blake’s notebook, written in 1792 when the fear of the French Revolution had reached levels of near hysteria in London and the king had stationed Prussian mercenary troops in and around the city:

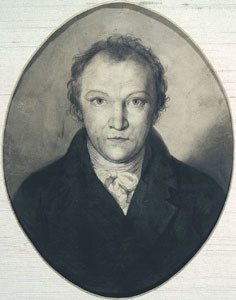

William Blake

I wander thro each dirty street

Near where the dirty Thames does flow

And see in every face I meet

Marks of weakness marks of woe

In every cry of every man

In every voice of every child

In every voice in every ban

The german forged links I hear

But most the chimney sweepers cry

Blackens oer the churches walls

And the hapless soldiers sigh

Runs in blood down palace walls

Read the whole “London” poem and see original illustration

Blake: A Biography is a fascinating account, meticulously researched and extraordinarily well written.

Damrosch includes the important biographical details of Blake’s life, but his Eternity’s Sunrise: The Imaginative World of William Blake focuses on Blake’s artistic vision. He addresses both Blake’s art and poetry, emphasizing how intimately the two were connected. But his primary focus is Blake’s art (the book includes two sets of black-and-white illustrations of Blake, various locations, and people he knew, and 40 color plates of his artwork).

Many fellow poets and artists thought Blake a bit mad (and often more than a bit), but Samuel Taylor Coleridge was one who saw Blake’s genius. Of course, Coleridge was himself given to visions.

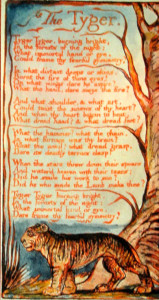

Blake’s works combining art and poetry included the familiar Songs of Innocence and Songs of Experience, but other subjects caught his eye as well. These included religious subjects, like The Marriage of Heaven and Hell; biographical subjects like Milton; the city of London as a kind of new Jerusalem; and apocalyptic subjects. He also created his own mythologies, and even was writing (and drawing) orcs almost 150 years before J.R.R. Tolkien.

Damrosch has also written The Sorrows of the Quaker Jesus: James Naylor and the Puritan Crackdown on the Free Spirit (1996); Jean-Jacques Rousseau: Restless Genius (2005); Tocqueville’s Discovery of America (2011); and Jonathan Swift: His Life and His World (2013).

The Tyger, poem in Songs of Experience

What Damrosch helped me to understand about Blake was how integral his art was to his poetry, and how integral his poetry was to his art. They were woven together as the same cloth.

The title, Eternity’s Sunrise, is taken from another unpublished poem found in Blake’s notebook:

Eternity

He who binds to himself a joy

Does the winged life destroy

He who kisses the joy as it flies

Lives in eternity’s sunrise

Blake’s life was a struggle for acceptance and understanding, as well as a financial struggle. It took more than a century, but he was eventually understood, as if he were writing for generations yet unborn. And he indeed kissed the joy as it flew.

Related:

Photo by Zach Dischner, Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post by Glynn Young, author of the novels Dancing Priest and A Light Shining, and Poetry at Work.

__________________________

“I require all our incoming poetry students—in the MFA I direct—to buy and read this book.”

—Jeanetta Calhoun Mish

- Poets and Poems: Mary Brown and “Call It Mist” - September 18, 2025

- “Horace: Poet on a Volcano” by Peter Stothard - September 16, 2025

- Poets and Poems: The Three Collections of Pasquale Trozzolo - September 11, 2025

Bethany says

Interesting to learn a bit about these Blake biographies. Fascinating how, as you said, “integral his art was to his poetry, and how integral his poetry was to his art. They were woven together as the same cloth.”

Glynn says

Bethany, in Blake’s case, the two were rather inseparable. In fact, he may have thought of himself as more of an artist than a poet, in the vein of “OK, here are the pictures, now I need the captions.” Thanks for the comment.

Sherry says

In my comment on the Whitefield bio, I meant eighteenth century, of course. The Akroyd biography sounds as if it would be good reading for this project, too.