It started at the British Library in London. In the library’s shop, likely my favorite shop of any institution in the city, I saw a pile of small (4 x 4 ¾ inches) books, each for a pound. And right on top was one about poet William Blake, William Blake’s Notebook, a little volume with drawings and notes from the notebook the poet and artist kept from 1787 to his death in 1827.

I read the little volume on the plane home. It would be equally accurate to say I looked at it and read the captions; it includes an explanatory text by Jamie Andrews, who works for the library and was the co-curator of the 2007 exhibition “William Blake: Under the Influence.”

Shortly after I returned home last fall, Harvard professor Leo Damrosch published Eternity’s Sunrise: The Imaginative World of William Blake. Coincidence, I thought. And then I discovered that one of my favorite popular history and biography writers Peter Ackroyd had published Blake: A Biography in 1995.

Shortly after I returned home last fall, Harvard professor Leo Damrosch published Eternity’s Sunrise: The Imaginative World of William Blake. Coincidence, I thought. And then I discovered that one of my favorite popular history and biography writers Peter Ackroyd had published Blake: A Biography in 1995.

I asked myself, how much did I really know about Blake?

What I knew stretched back (way back) to high school and college, where poems from Songs of Innocence and Songs of Experience were included in textbooks. I know he was loosely and incorrectly associated with the Romantic poets; he was actually a generation before them. And I knew he had drawn illustrations for his poems, or perhaps it was more he had written poems for his illustrations.

Between the little notebook volume, the Damrosch book, and Peter Ackroyd, I dove into the poetry and art of William Blake. It turned out to be a surprising dive.

From the time he was a child, Blake had visions. This was not necessarily unusual in the latter part of the 18th century, and not unlike all of the dystopian books, movies, and television programs of our own era. It may have run in Blake’s family—his older brother James had them as well. The difference was that Blake drew and wrote what he had experienced, and many of his contemporaries thought him more than a little mad.

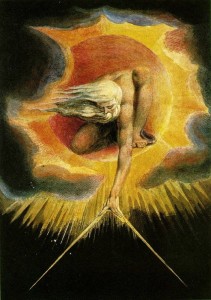

The Ancient of Days by William Blake (1794)

His parents recognized his artistic skill. He was not pushed into the family hosiery business but was given art lessons and eventually apprenticed to a printer and engraver. He was eventually accepted into the Royal Academy school, but he left it for the engraving business, and it was what provided an income for him and his wife for the rest of his life.

Blake experienced periods of decent income, but most of his life was a financial struggle. He had patrons for most of his career, a common enough occurrence at the time for artists, but his personality was such that he could easily offend. Once he offended a soldier, and found himself charged with and put on trial for sedition. He was found not guilty, but it was a close thing.

A great part of his inspiration (and perhaps his visions) came from religion and the Bible. His family were Dissenters, but that is a broad term covering all kinds of groups, from Puritans and Anabaptists to Quakers, Seekers, and “Muggletonians.” They were definitely not Church of England; his parents (and eventually he himself) were buried in the Dissenters’ cemetery. Blake struggled with religion, and that struggle played out in both his poetry and his art. Ackroyd calls Blake “the last great English religious poet, ” and I think he’s right, but it’s a broad definition of “religious.”

Blake involved himself in social causes. He was friendly toward the French Revolution, even when it became dangerous in England to be friendly in that direction (once the Terror began). He wrote poems about the plight of chimney sweeps, young children essentially enslaved to clean chimneys. He wrote about poverty and the poverty of children, like in this poem:

Holy Thursday

William Blake

Is this a holy thing to see

In a rich and fruitful land,

Babes reduced to misery

Fed with cold and usurous hand?

Is that trembling cry a song?

Can it be a song of joy?

And so many children poor?

It is a land of poverty!

And their sun does never shine.

And their fields are bleak & bare.

And their ways are fill’d with thorns.

It is eternal winter there.

For where-e’er the sun does shine,

And where-e’er the rain does fall:

Babe can never hunger there,

Nor poverty the mind appall.

He generally published his own books, often printing only a few copies at a time, with his wife Catherine typically coloring the engravings. One of his best known works (and to call it “best known” is stretching the reality a bit, at least for a long time after his death) was Songs of Innocence, and it was popular as poems that could be read to children.

He was largely unknown in his lifetime, and forgotten for decades. It was later in the 19th century and more fully in the 20th century that his poetry became well known and the genius of the man appreciated. His work became especially popular in the 1960s, when even Jim Morrison borrowed a line from a Blake poem to name his band “The Doors.”

Next week, I’ll take a more in-depth look at Ackroyd’s biography and Damrosch’s study of Blake’s artistic vision.

Photo by Seabamirum, Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post by Glynn Young, author of the novels Dancing Priest and A Light Shining, and Poetry at Work.

__________________________

“I require all our incoming poetry students—in the MFA I direct—to buy and read this book.”

—Jeanetta Calhoun Mish

- “Horace: Poet on a Volcano” by Peter Stothard - September 16, 2025

- Poets and Poems: The Three Collections of Pasquale Trozzolo - September 11, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Boris Dralyuk and “My Hollywood” - September 9, 2025

Mary Harwell Sayler says

Interesting word, Glynn. Thanks. I’ve never been a big fan of Blake, but your post invites me to read more.

Glynn says

Thanks for reading the post, Mary. I wasn’t familiar (or interested) with him or his work myself, until I picked up that little book in the shop.

Maureen says

Nancy Willard wrote a children’s book, ‘A Visit to William Blake’s Inn: Poems for Innocent and Experienced Travelers’. It’s a lovely book. Perhaps something to share with your grandchildren.

Glynn says

Maureen – I will check into it. Thank you!

Bethany says

That line from “Holy Thursday” is just crushing:

“Is that trembling cry a song?”

Glynn says

I want to add, “or is that song a trembling cry?” Thanks for the comment, Bethany!

Rick Maxson says

Wonderful post, Glynn. And what a poem for these times as well.

Marilyn Yocum says

Illuminating! I enjoyed reading this. Looking forward to next week’s edition. For the record, I am not jealous of your trip to the British Library’s shop, no matter what anyone says. ?