Poets have been writing about exile at least as far back as Ovid’s exile to the Romanian coast of the Black Sea by the Emperor Caesar Augustus in 8 A.D. “Our native soil draws all of us, ” he wrote in one poem, “by I know not what sweetness, and never allows us to forget.” Exile is about both the present moment and memory, and about both simultaneously.

Two recent collections of poems explore the idea of exile, but they do it in very different ways.

Lucia Cherciu

Lucia Cherciu is a professor of English at the State University of New York in Dutchess/Poughkeepsie. She was born in Romania, and in fact has had two collections of poetry published there—The Abandonment of Language (2009) and Gifted Laughter (2010), both by Editura Vinea Press in Bucharest. She writes in both English and Romanian, and her first book of poetry in English, Edible Flowers, was published in 2015.

While not all of the poems are about exile, many of them are, about a life and people left behind, about a people nearly destroyed by the Communist regime under Nikolae Ceaucescu. The poems consider what’s missing, what is remembered, what life was like and not like. And the poems address what it means to return, when return becomes possible.

A Tour of the Ceausescu Palace

we waited in line after a long walk

on threateningly straight streets,

trying to imagine what the houses

looked like before

the neighborhood was erased.

Inside, the tour guide

told us she had two stories:

one for foreign tourists

and one for the Romanians

in the room, depending

on which group came in.

Sometimes, people whose houses

had been destroyed

corrected each of her words.

No pictures of Ceausescu and his wife.

Only in the basement, we found

the image of the scythe and hammer.

You were impressed with the candelabrum

that weighed fourteen tons. I could only see

the dozens of conference rooms

and the rhythm of hands clapping

at the macabre wooden tongue.

Edible Flowers is a moving collection, tinged with both a sense of sadness and a determination to go on, because not to go on is to die.

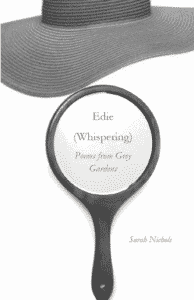

Sarah Nichols

The chapbook Edie (Whispering): Poems from Grey Gardens by Sarah Nichols is about a different exile—a kind of exile by choice in one’s own country—or one’s own house.

The collection is all found poems, taken from a 1975 documentary entitled Grey Gardens. The subject of the documentary is a woman and her daughter: “An old mother and her middle-aged daughter, the aunt and cousin of Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, live their eccentric lives in a filthy, decaying mansion in East Hampton, ” according to the official description.

Nichols has taken words and phrases from the transcript of the documentary and transformed them into poems. The mother speaks in some of the poems; we’re hear the daughter’s voice in others. Here is the mother speaking:

Come here—back here.

Everything disappears in this place,

and we

couldn’t possibly leave.

Night after night, morning

after morning, the ghosts

hold our breath.

What was the point of my

searching the line between

the past and the present ?

Would you tell me ?

This woman is lost,

and I couldn’t possibly leave.

Nichols is the author of a previous collection of poetry, The Country of No (2012), published by Finishing Line Press. Her poems have appeared in numerous literary journals and publications.

The poems in Edie (Whispering) make sense of an exile of choice. One thinks of Miss Havisham in her wedding dress in Great Expectations by Charles Dickens, but the mother and daughter in this poetry collection are not isolated because of a jilting at the altar. Instead, their exile by choice seems more driven by fear.

As Ovid suggested, exile does not allow us to forget. In fact, it forces our reality into memory.

Related:

Lucia Cherciu reads the poem “Geraniums” at The Cortland Review.

An interview with Sarah Nichols at The Found Poetry Review.

Photo by Rob Franskdad, Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post by Glynn Young, author of the novels Dancing Priest and A Light Shining, and Poetry at Work.

__________________________

“I require all our incoming poetry students—in the MFA I direct—to buy and read this book.”

—Jeanetta Calhoun Mish

- 10 Great Resources for Teaching the Civil War - March 6, 2025

- Relearning Civil War History to Write a Novel - March 4, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Marjorie Maddox and “Seeing Things” - February 27, 2025

Rick Maxson says

“As Ovid suggested, exile does not allow us to forget. In fact, it forces our reality into memory.”

What a powerful line to end this post. We are being made aware of many types of exile these days from the Middle East to our own inner cities and social consciences.

The first three lines of Cherciu’s poem seemed to address forcing reality into memory:

“Although I didn’t want to see it,

we waited in line after a long walk

on threateningly straight streets,”

Where Cherciu evoked in me a sense of forced memory, Nichols’s poem began with being exiled between two worlds: here and not here.

Everything disappears in this place,

and we

couldn’t possibly leave.

Regarding the last line about memory, I just finished a book by a Belarusian poet (the first to be published in English), Valzhyna Mort, called “Factory of Tears.” She writes:

and now: imagine

somewhere there are towns

with white stone houses

scattered along the ocean shore

like the eggs of gigantic water birds

and every house carries a legand of a captain

and every legend starts with

“young and handsome…”

Glynn says

Rick – thanks for the great comment!

Bethany says

Cherciu’s second stanza communicates so much in just a few words:

“…she had two stories:

one for foreign tourists

and one for the Romanians”

And what a fascinating question posed in Nichols’ piece concerning:

“the line between

the past and the present ?”

Thank you for this post, Glynn.

Glynn says

Bethany – the poems in both collections are full of these kinds of lines, taking you where do do — and don’t — expect. Thanks for the comment!