When we read a poem, or a collection of poetry, we rarely make a connection to the poet’s geography, unless the poems are specifically about a place or a historical event, like Alfred Lord Tennyson’s “The Charge of the Light Brigade, ” Robert Frost and New England, or Matthew Arnold’s “Dover Beach.”

When we consider Walt Whitman (1819-1892), we might think of Washington, D.C., where he worked in the hospitals during the Civil War, or perhaps Camden, New Jersey, where he spent the last days of his life. And yet if there is one location that had a powerful influence on Whitman and his poetry, it was Brooklyn, New York.

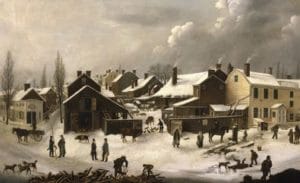

Brooklyn in 1830 by Francis Guy – the area where the Whitman family first lived

Born on Long Island, Whitman was not quite four years old in 1823 when his father moved the family to Brooklyn, where they settled in a rental house on Front Street, according to Walt Whitman: A Life by Justin Kaplan. At the time, Brooklyn was the third largest city in the United States and exploding with growth, which Whitman’s father hoped to get a piece of.

From 1823 to 1835, Whitman lived at various addresses in Brooklyn. One of his earliest memories was watching the aged American Revolution hero the Marquis de Lafayette dedicate a Brooklyn library. When Whitman was 11, he was apprenticed to a printer, and served as office boy, delivery boy, and eventually printing itself. He would later tell the story of how frequently he crossed the Hudson on the Brooklyn Ferry, to deliver printing proofs to various customers, including Aaron Burr.

The Brooklyn Eagle

His apprenticeship finished in 1835. He crossed the river and spent the next 10 years working in New York City, primarily in printing but also trying his hand at writing. He returned to Brooklyn in 1845, to work for a short time for the Brooklyn Star newspaper and then becoming editor at the Brooklyn Daily Eagle. (Tania Wojczuk at Tin House has a concise summary of his work at the Eagle.)

Here at Brooklyn’s largest newspaper, he wrote on such issues as slavery and manifest destiny. He opposed the idea of popular sovereignty (articulated most famously by Stephen Douglas). Eventually dismissed by the Eagle, he left Brooklyn for a short time to become editor of the Crescent in New Orleans, but returned the same year and eventually established the Brooklyn Freeman, a newspaper supporting the presidential candidacy of Martin Van Buren. After its first issue, a fire destroyed the area around Fulton Street, where it was published. By November, he was able to resume publication.

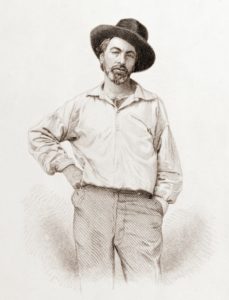

Whitman in 1848

He lived on Prince Street with his family, but eventually found his way to Myrtle Avenue. He became what today we’d call a property investor and developer, buying several houses on Cumberland Street. By the early 1850s, he was also working in New York and moving in literary, journalistic and artistic circles there and still managing properties in Brooklyn. In May 1854, he moved to a house on Skillman Street, and the next year to 99 Ryerson Street, where he finished work on Leaves of Grass.

Registered for copyright in May 1855, the poetry collection was being sold by July. Whitman had set the type himself at the printer’s shop in Brooklyn. Ralph Waldo Emerson was one of its wildly enthusiastic readers. “I find it the most extraordinary piece of wit & wisdom that America has yet contributed, ” he wrote in a letter to Whitman.

In 1856, Whitman published “Crossing Brooklyn Ferry, ” which was added to the 1860 edition of Leaves of Grass.

He moved between Brooklyn and New York for the next several years, and was in New York when the Civil War began. At the end of 1862, he left New York for Washington, D.C.

Whitman in 1854; used with Leaves of Grass

In addition to “Crossing Brooklyn Ferry, ” it is in “Song of Myself” in Leaves of Grass (with that wonderful prose-poem-like introduction) that one can see the sights, sounds and people of Brooklyn. And Whitman identifies with all of them—the butchers, the runaway slaves, the carpenters, the farmers, the printers, the spinning-girls, the machinists, the deckhands, the reformers, the young wives (and the old), the canal-boys, and more. Whitman spent 22 years of his life absorbing the sights and sounds of Brooklyn, and often reporting on them.

It is Brooklyn that became the poems of Leaves of Grass. And Whitman took what he saw as an extraordinary place and made it more so.

Related:

Walt Whitman’s Guide to Brooklyn, a photo essay by Conde Nast Traveler.

Walt Whitman and the Arts in Brooklyn, 1823-1860s, a photo essay by the Brooklyn Museum.

Brooklyn’s History Enlarged: Illustrations of Whitman’s Brooklyn in the mid-19th century.

An excerpt of “Song of Myself, “ read by Tom O’Bedlam.

Photo by misselejane, Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post by Glynn Young, author of the novels Dancing Priest and A Light Shining, and Poetry at Work.

__________________________

“I require all our incoming poetry students—in the MFA I direct—to buy and read this book.”

—Jeanetta Calhoun Mish

- Poets and Poems: Siân Killingsworth and “Hiraeth” - March 25, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Donna Hilbert and “Gravity” - March 20, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Emily Patterson and “So Much Tending Remains” - March 18, 2025

Ayietim says

Whitman, a great poet, a great writer and a lyricist that wrote great stories in poetry.

Bethany says

Ayietim, welcome to Tweetspeak Poetry! If you haven’t already visited our welcome space, The Mischief Cafe, it’s a fun spot to find our monthly theme, poetry promps, and other goodies. -> https://www.tweetspeakpoetry.com/mischief-cafe/

Glynn says

Thanks for reading, Ayietim!

Bethany R. says

“When we read a poem, or a collection of poetry, we rarely make a connection to the poet’s geography, unless the poems are specifically about a place…” Excellent point, Glynn. And physical geography can inform the writing in a rich way. Thank you for the history here on Walt Whitman’s “home town.”

Glynn says

Bethany – I think only skimmed the surface of Whitman’s time in Brooklyn. He wrote hundreds of newspaper editorials and articles, and was an early proponent of abolition. And the idea of him poring over his page proofs of “Leaves of grass,” making his own corrections and changes — that’s probably a book in and of itself. Thanks for reading!

L. L. Barkat says

Always so interesting to see how poets support themselves and what roles they play in society beyond “poet.” A developer? Who knew 🙂

(And I love that painting of early Brooklyn!)

Glynn says

Poets have to do something to support themselves. I’ve always said only three poets in the US make a living from poetry, and two of them are Billy Collins.

Rick Maxson says

Glynn, you always bring such a fresh perspective on poets/authors new and familiar. This was no exception, but it is one of my favorites.

I particularly honed in on Whitman’s apprenticing to a printer at age 11. That had to have influenced greatly who he became. Being an apprentice (not the Trump variety) to a specific vocation at an early age might serve a child far better that “middle school.”

I have never read the 1855 edition but I have one on the way. Thanks for writing this.

Glynn says

Rick – I was more familiar with Whitman’s years in Washington, D.C., and his experience with the wounded of the civil War. I knew his early years had been spent in Brooklyn, but what I didn’t know was how truly formative those early years were for his poetry. And the connections to newspapers — typesetter, reporter, editor — rolled him into politics, journalism, and the life around him.

Separately, I’ve been reading several books published decades ago about 19th century American literary life and how a national literary “self” was shaped for the United States. Building on the Emersons, Hawthornes, Irvings, and other earlier authors, three authors particularly shaped the 19th and the 20 centuries in a literary sense — Melville, Whitman (both born on the same day in the same year), and Twain.