This year marks the 400th anniversary of the death of William Shakespeare. While Great Britain, never a slouch in the “can we find some anniversary celebration to draw tourists” department, has all kinds of recognitions and celebrations underway in Stratford-on-Avon as well as the rest of the country, the United States is mounting its own extensive series of Shakespeare festivities. And The Bard would likely smile to know he’s become a hashtag on Twitter: #Shakespeare400.

“@RomeoMontague: Hark! What tweet through yon window breaks? It is the moon, and @JulietCapulet is the sun. #Shakespeare400.”

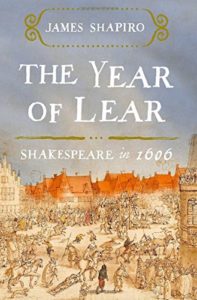

One of the best recently published books on Shakespeare has less to do with the quadricentennial celebration and more to do with what happened a little less than 400 years ago—1606 to be precise. The Year of Lear: Shakespeare in 1606 by James Shapiro, the Larry Miller Professor of English at Columbia University, is a wonder of re-creation of that year in Shakespeare life.

At the time, Shakespeare had been rather out of the picture for writing plays. The death of Queen Elizabeth I (1533-1603), the last of the Tudors, might have been a dampening influence on Shakespeare’s writing and producing new plays.

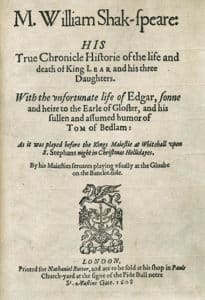

Shakespeare would likely have been writing King Lear in late 1605, when the news of the Gunpowder Plot—the plan to blow up the royal family and Parliament on November 5—rocked the country. The trials of the conspirators continued in early 1606, and Shapiro shows how the plot affected Shakespeare’s writing of the great tragedy of Lear. He also includes a delightful discussion of the theme of “nothing” as a powerful factor in the play. (Little did I know that “Something Good, ” sung in The Sound of Music by Maria, includes the lines “Nothing comes from nothing, nothing ever could, ” which are likely borrowed from King Lear; that’s my observation, by the way, not Shapiro’s).

Other significant events of 1606 that would have been influencing Shakespeare with all three plays were the desire by King James I for union between England and Scotland, a desire that would be frustrated for another century; the always simmering religious controversy, bubbled to the surface by the Gunpowder Plot which was often called the “Jesuit Treason”; various cases of suspected witchcraft (James I had written a book on the subject); and recurring outbreaks of the plague.

James Shapiro

Shapiro knows his Shakespeare. He’s the author of A Year in the Life of William Shakespeare (2009), about the year 1599; Contested Will: Who Wrote Shakespeare? (2010); and Shakespeare and the Jews (1986; reprinted in 2016). He also served as editor of Shakespeare in America: An Anthology from the Revolution to Now (2014).

The Year of Lear is a masterful account of how Shakespeare wrote the three tragedies, including two of his most important works—King Lear and Macbeth. And it is a masterful account of how his contemporary context shaped what he wrote, how he wrote, and why he wrote.

Photo by Kurtis Garbutt, Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post by Glynn Young, author of the novels Dancing Priest and A Light Shining, and Poetry at Work.

__________________________

“I require all our incoming poetry students—in the MFA I direct—to buy and read this book.”

—Jeanetta Calhoun Mish

- Poets and Poems: Forrest Gander and “Mojave Ghost” - March 27, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Siân Killingsworth and “Hiraeth” - March 25, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Donna Hilbert and “Gravity” - March 20, 2025

Bethany R. says

Interesting to hear about the historical events these plays were written in. I didn’t know about Shakespeare’s daughter refusing to take that oath at first. Wow.

Glynn says

Shapiro spent a lot of time researching local documents, both in London and Stratford. I didn’t know about Susanna, either, or that the Gunpowder Plot extended to people in the region of Stratford.

Thanks for the comment!