With a little February rain, icicles emerge from the strata of rock rising one hundred feet above Spring Street in Eureka Springs, Arkansas. As the day progresses they vanish into the air, like the ghosts, legends say, that inhabit the nearby Crescent Hotel.

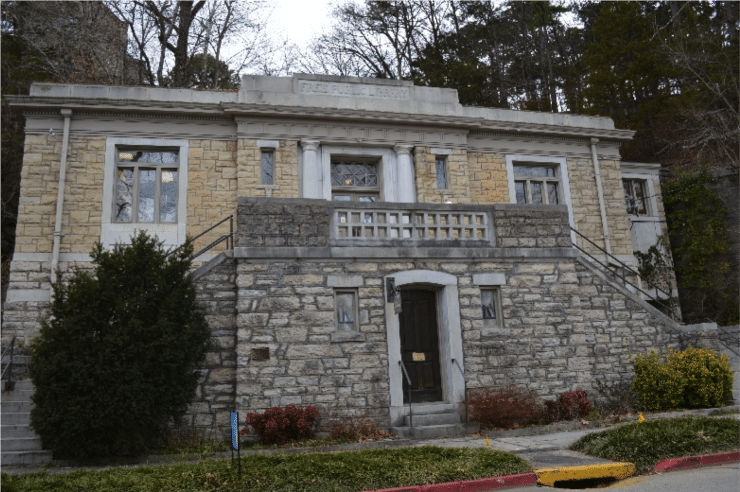

Green tips of jonquils, harbingers of spring, attend themselves in short rows and irregular clusters from the limestone cliffs. In relief from these same bluffs, the broad shoulders of a compact building, donated by Andrew Carnegie, rise over the narrow, century-old avenue. On its facade, the spirit of its benefactor is inscribed in stone: FREE PUBLIC LIBRARY.

Eureka Springs Carnegie Library

The library is not a big building, but it appears massive, seemingly incapable of being razed by nature or human. I take comfort in this perception, as it is one of only two remaining Carnegie libraries in Arkansas.

During his lifetime, Andrew Carnegie donated 90 percent of his wealth to philanthropic goals. One of these goals was to make available to the state of New York 5.2 million dollars to build sixty-five branch libraries. Carnegie was inspired by the memory of having access, as a young man, to the personal library of colonel James Anderson. As news of his generosity spread, he received requests from all over the world. The first Carnegie library in the United States was built in 1889 in Braddock, Pennsylvania. By the time of his death in 1919, Carnegie had provided 41 million dollars to build libraries worldwide, including 1, 946 libraries in the U.S. alone.

In Arkansas, four libraries were built from four separate Carnegie grants: Fort Smith in 1908, Little Rock in 1910, Eureka Springs in 1912, and Morrilton in 1916. The Fort Smith library was converted to a television station in 1970. The august Little Rock library was demolished in 1964 to build a more modern library.

The grant of $12, 500 for a library in Eureka Springs was received in 1906. St. Louis architect George W. Hellmuth was hired as the architect to build the library and a site was chosen, but was subsequently considered instead for the Eureka Springs Post Office. In 1910, R.C. Kerens gifted a new site for the library on Spring Street, where a gazebo with opposing stairs stood on the hillside and served as the entry point to the Crescent Hotel by way of a long flight of stairs.

Gazebo with stairs to Crescent Hotel

Unpredictable Arkansas winters and problems excavating and building on the jagged rock delayed construction. The Library Board of Trustees made numerous petitions to Carnegie for an additional $3000, and in 1910 they received the requested funding to complete the library in 1912.

Few structures seem to emerge from the terrain around them in the manner of the Carnegie library. It declares itself as something revealed from within the rock face so typical of the Arkansas and Missouri Ozarks.

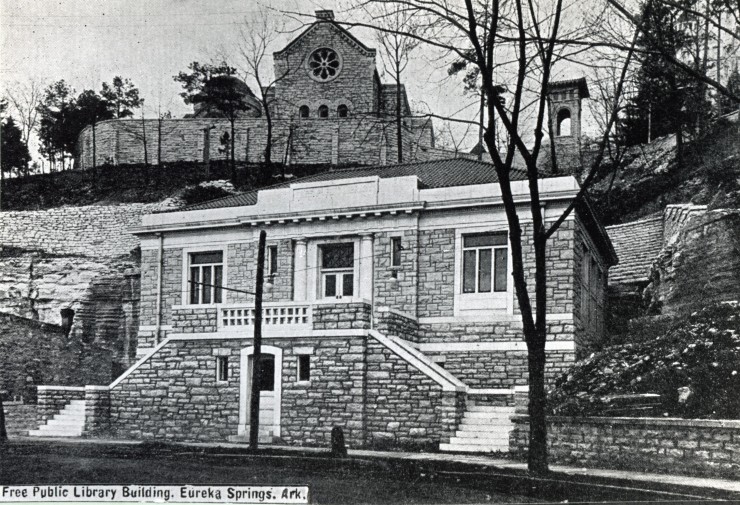

1912 photo of completed library – no elevator

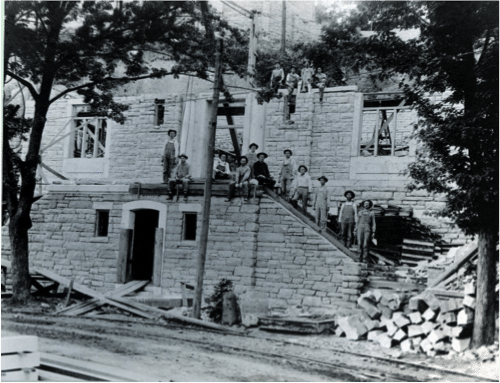

In one of the few photographs of the library in mid-construction, carpenters and stonemasons pose in the front, the basement door and windows barely framed. The dense, heavy limestone blocks are stacked in a pile waiting to be set. The gazebo stairs, where hotel guests in their fine clothes once sat for a photo, are incorporated into the front stairs where the builders stand. The original stairs leading up the steep hillside to the Crescent Hotel are gone to make way for library interior and the towering, thick retaining wall I saw through one of the windows during my first visit.

Looking at one of the early photographs of the finished library, before the hillside regained its flora in the ensuing years, I can see the source of my current day impression that the Eureka Springs Carnegie Library was sculpted from the Spring Street limestone precipice: The builders stand and sit, with their hand tools, on the shell of this magnificent building.

1911 photo of workers in front of partially completed library

Approaching the stairs, I am warned by a plaque that they are formidable and there is an elevator to the right. My intent is to immerse myself in the library’s history. I feel I must climb the stairs where the guests once sat and the craftsmen stopped working for a photograph. I sit halfway up and try to imagine a Sunday with friends, the women in their long dresses and the men in seersucker suits and straw hats, having descended the stairway from the hotel to sit for an image over one hundred years ago.

People seated on gazebo stairs

The modest but sturdy front entrance with its wooden doors keeps me walking in this fin de siècle. I take the five stairs rising between two stone columns on either side of the doors, and I step inside a small foyer where George W. Hellmuth’s original 1909 blueprint hangs in a glass frame on the wall. Leaving the foyer, I enter onto the original brick-colored tile floor. In the middle of the floor, between two opposing lofts of stacks, is a long oak table with periodicals.

Beyond that, on the back wall, is a fireplace mantel with a sconce on either side, one needing a new bulb. The sconces are additions—I can tell by the markings behind them they were once gas lamps. In the middle is a portrait of Andrew Carnegie. The names of the board, builders and benefactors are painted across old tile blocks.

Fireplace in Eureka Springs Carnegie Library

Sitting at the oak table, I drift once again into the past. The fireplace is warming the small room. The newly painted face of Carnegie flickers in the glow. There is a stack of wood near the hearth. One of the gas lamps has gone out and I smile, knowing soon our new library will be getting electric lights. It is 1917. On the table is a copy of our newspaper, the Eureka Springs Echo. A woman sits down across from me and says hello. This brings me back to the present.

I greet her and wander up the stairs to the north loft, pausing to look through a back window at the sheer cliff and retaining wall. There are several stacks of young adult books on stained oak shelves that seem newer than the large wooden columns and beams supporting the loft. I stop to inspect one closely and notice a crack in the veneer of the crown molding, which only adds to the charm of this majestic building.

On one of the walls of the loft is a photo of school children with the dedication, Carnegie Rising: The Second 100 years of Eureka Springs Carnegie Public Library 2010. During my visits to the library, I haven’t seen any children inside. So, I’m happy to see this photograph and the small display of young adult books that represents the involvement with students. After a brief tour of the second loft and the poetry section under it, I see a corner dedicated to very young children.

I ask to see the library basement.

“I have read about the tunnels, from here to the Crescent Hotel, ” I say.

“Oh, ” responds a librarian, “I’m not sure about those, but the basement is full of construction equipment now. We are renovating. Last May we added the annex next door. You wouldn’t want to see that anyway; it’s dark and damp and creepy.”

“Now I really want to see it, ” I say and we both laugh.

“There are some photos here.” She points to a small file with photos of Eureka Springs from the 1800s to the present. “Also, the History Museum has even more. You may find photographs of the basement in those.”

I thank her and head for the door to leave. At the oak table, I look around. From here I scan the library’s interior once again: the “great room” with its hearth and inscription, the four sections of stacks, lofts and main floor, the front desk where volunteer librarians are busy helping a local resident with some posters. To the right of the front desk, a short hallway leads to the elevator for those wishing to avoid the concrete stairs to and from Spring Street.

It is intimate here. On the table are the unassembled pieces of a jigsaw puzzle and I remember the photograph upstairs of the students. Richard Kerens donated the land for the library on the condition that it always remain a Carnegie library. Otherwise, the land would be deeded back to him. Given the predominance of electronics these days, I hope the students here realize what they have available to them for free. I hope they learn the spirit of generosity that made this place.

Photo by Adam Tinworth, Creative Commons, via Flickr. Historical photos courtesy of the Eureka Springs Historical Museum, used with permission. Post by Richard Maxson.

Browse more Best Buildings

Browse more libraries

Browse Literary Tours

Browse Regional Tours

__________________________

Subscribe to our free weekly newsletter.

We’ll make your Saturdays happy with a regular delivery of the best in poetry and poetic things.

Need a little convincing? Enjoy a free sample.

- Pandemic Journal: War is Over (If You Want It) - January 7, 2021

- Pandemic Journal: An Entry on How We Learn - April 23, 2020

- Adjustments Book Club: Homecomings - December 11, 2019

Bethany R. says

Oh, the crack in the molding, the plaque preparing you for the stairs, the markings of the gas lamps, what a charming telling of this library. Loved learning a bit of the history and generosity behind it.

Your piece inspired me to look up the Carnegie libraries in my own state. I was delighted to find out there is one in Pt. Townsend, on the same street as my most favorite restaurant in Washington. I can’t wait to take the ferry back over to Sweet Laurette Cafe & Bistro, sip on a Cafe Borgia in their herb garden and then walk for “one minute,” (according to Google Maps) to visit their still-operational library. Thank you so much, Rick.

Rick Maxson says

Thank you for reading and commenting, Bethany! Maybe you could write a piece on your Carnegie library. I’m sure there is an interesting history there as well.

Bethany R. says

What a lovely idea, Rick. Pt. Townsend is a lovely, historic town that my husband and I try to visit each year on our anniversary. The whole quiet adventure of riding the ferry from bay to bay, walking from the dock up through the old neighborhoods to the bistro, and exploring this Carnegie library would certainly be brimming with writing possibilities. Next time I go, I’ll bring my journal.