I leave London’s Circle Line underground train (aka The Tube) at Temple Station, adjacent to The Temple, the legal center of London with two of the four Inns of Court, Middle Temple, Inner Temple, and Temple Church. It’s raining, and I fortunately brought my umbrella. From the Tube station, I walk what are essentially back alleys and narrow delivery streets, passing not a few pubs, some older than the United States. Think Pomeroy’s Bar in Rumpole of the Bailey, the pub which provided Rumpole with his “Chateau Thames Embankment” white wine.

When I reach Fleet Street, which becomes the Strand going west and Cannon Street going east, the setting becomes even more Rumpole-like. The front windows of several clothing shops feature the black gowns and white wigs worn by attorneys in court; one is even advertising a special price for the entire ensemble for only 599 pounds (about US $1, 000).

Samuel Johnson House on Gough Square, London

I walk east, and can’t help but notice the huge edifice of St. Paul’s Cathedral dominating the skyline. My destination will stop a few blocks short of St. Paul’s. I’m looking for 167 Fleet, which is the closest address to a meandering alleyway. A small sign at the alley’s entrance contains the words I’m looking for: “The Samuel Johnson House.”

I’ve been to London several times, but have never visited the Samuel Johnson House in Gough Square. The great lexicographer lived here for only about 10 years, but it was a critical 10 years—the period he wrote and assembled his dictionary. This work served as the pre-eminent dictionary of the English language for more than 150 years, until the Oxford English Dictionary (the O.E.D. for short) was published. Quite a good run for a book.

The alleyway takes a number of twists and turns, and several times I wonder if I’ve passed the house without realizing it. And then I’m there, in Gough Square. The house is unmistakable—the only 18th century building around. Up a short flight of steps, and I’m inside. The fee is reasonable (about US $7 for adults and $5.50 for seniors) and I pay the extra pound or so for the headset tour.

If you go, don’t stint on the headset. It’s well worth the money; the guided tour is filled with fascinating details you would miss without it, such as why there is a metal bar crossing the transom over the front door. In the 18th century, before London had a police force, life on the streets could be interesting. Criminals seeking to rob houses would often break the glass over the transom and lower a child down through the opening to open the door. And what looks like a place to insert mail was actually a kind of peephole—useful if, like Johnson, you were constantly being harried by creditors.

The primary room on this main floor is a kind of parlor, where Johnson (1709-1784) took his meals and often had friends for a glass of wine and conversation. And what friends: Sir Joshua Reynolds, the painter and president of the Royal Academy of Arts; Edmund Burke, the parliamentarian; the playwright Oliver Goldsmith; the actor and producer David Garrick; and James Boswell, Johnson’s biographer.

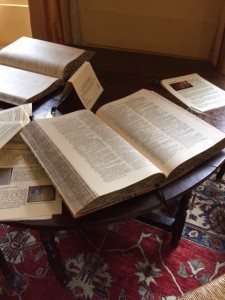

A facsimile of Dr. John’s dictionary

The next floor, reached by the spiral-like staircase, is where Johnson would have officially entertained, and includes both a dining room and drawing room. The floor above it housed Johnson’s bedroom; it now looks like a library, with display cases, bookshelves, and a facsimile of the two-volume dictionary open on a table for perusing.

The top floor is the ultimate destination. It runs the entire length of the house, a large open room where Johnson wrote the dictionary and supervised the work of clerks involved in the project. At this time, it’s also the room for a small but fascinating exhibition on how Johnson and his close friend David Garrick, an actor and play producer, resurrected Shakespeare, whose plays hadn’t been performed in more than a century. In another great publishing project, Johnson painstakingly assembled the Shakespeare folio, determining which scripts were the most reliable. Garrick undertook a restaging of several of them. Together, they may well have saved Shakespeare from obscurity.

Samuel Johnson

This attic-like space is interesting for another reason. During World War II, the director of the Johnson House allowed rooms to be used for tea breaks for the firemen fighting the fires from the blitz, and often allowed firemen to sleep there. The surrounding area was nearly leveled by bombing, and the Johnson House itself was hit several times, once by an incendiary bomb which did serious damage to the roof and attic. The house was saved by the presence of the firemen. (This detail is another good reason to get the headset tour.)

Descending the stairs to the main floor, I spend some time in the small shop, where you can buy everything from Boswell’s Life of Johnson to tea and coffee cups bearing Johnson’s likeness. I can see through the windows that it’s raining harder. Suddenly the door opens, and some 30 law students from the nearby University of London crowd in, or try to, as the line extends outside. They’re here for a tour; their professor is going to instruct them on how Johnson affected the English language and (indirectly) English law.

I leave, to return to the Temple Tube station. But I’m intrigued. On the third floor of Dr. Johnson’s House, with the exhibits, books, and facsimiles, I discovered that Johnson’s professional life was bookended by poetry. And that’s the story for next week.

Photo by Davide D’Amico, Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post by Glynn Young, author of the novels Dancing Priest and A Light Shining, and Poetry at Work.

__________________________

“I require all our incoming poetry students—in the MFA I direct—to buy and read this book.”

—Jeanetta Calhoun Mish

- Poets and Poems: Paul Pastor and “The Locust Years” - June 26, 2025

- What Happened to the Fireside Poets? - June 24, 2025

- “What the House Knows”: An Anthology by Diane Lockward - June 19, 2025

Bethany R. says

Thank you for writing and sharing this piece. So interesting to hear how the this scholarly house was at times a respite for firefighters. Looking forward to the next installment and hearing about those poetic bookends.

Glynn says

Bethany – thanks for reading – and the comment.