Perhaps it comes from having a long, rather unexpected career as a speechwriter, but I tend to listen carefully to spoken language, both in real time and through various media reports of what people have said. You might imagine that the presidential election cycle sends my brain into overdrive, as if someone is pouring political phraseology through large funnels into both ears.

My solution is to not watch or listen, or at least not listen much. Language and how it’s used is important to people who write speeches as well as other things, and language does not usually fare well during political seasons. It even spills over into sports. Do you know that according to Wired Magazine, if you go anywhere near the Super Bowl you will be “surveilled” hard? And I think that, without having watched a single political debate all the way through, I can tell you the “message points” of all the candidates.

My preoccupation with language came to mind while reading Danniel Schoonebeek’s first poetry collection, American Barricade. It’s an unusual collection: the poems are unusual, the structure is unusual, and the close blending of the personal and social is unusual. That said, Poets & Writers called it one of the 10 best collections published in 2015, the Poetry Foundation has awarded Schoonebeek a Ruth Lilly and Dorothy Sargent Rosenberg Poetry Fellowship, and the collection has been widely praised as one likely to influence poetry for some time to come.

In these 58 poems, Schoonebeek alternates between what one might call social poems and personal poems (the personal poems are called “family album”). And the personal become the social, and the literary and social become the personal. Threaded through all of the poems is how he uses language—incomplete thoughts, incomplete sentences that may or may not finish in the next line. At first it’s disconcerting, and then comes understanding. Here’s an example:

My god can he hide a nickel.

My god his tooth is gold and like a bullet.

And do you see the way the coin.

When he touches its face it disappears.

And if he takes my hands, which I was saving.

If I place them on his table, which collapses.

It is almost too bright now, this setting.

This west where I have still not heard my numbers.

It is almost Black Friday.

And may I thank you for the ticket that wins nothing.

For the bag of mint too rotten to eat.

May I thank you for your death, and for your clothing.

Now, when it’s almost never closing.

When the door disappears, and the siren begins.

And my god if I could push my way past you.

Language, or how language is used, is the barricade. In the larger context of this collection, language becomes the barricade, the American barricade. It’s a difficult collection to read, but the effort is ultimately rewarding.

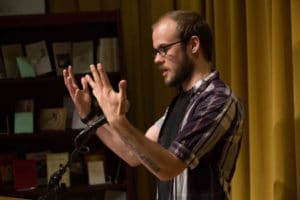

Danniel Schoonebeek

Schoonebeek’s poems have appeared in Poetry, Iowa Review, Boston Review, Indiana Review, Guernica, The New Yorker, and Kenyon Review, among others, and in several anthologies. In addition to his fellowship, he’s received a number of awards and honors. His second collection of poems, Trebuchet, was a winner of the 2015 National Poetry Series and will be published this year by University of Georgia Press. C’est la guerre, a collection of poetry, travel articles, and reflections, is scheduled for publication in 2017 by Poor Claudia Press. He hosts the Hatchet Job poetry series in Brooklyn and is an editor of the PEN Poetry Series.

American Barricade is not easy or light reading. It requires close attention. It often requires rereading the poems. The poems are not what many would call “beautiful” but they are certainly what I would call “important” poems. The collection is important for what Schoonebeck says in it. And what he says is that language matters.

Related:

Purchase College, Schoonbeek’s alma mater, interviewed him about his poetry last fall.

Photo by Diana Robinson, Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post by Glynn Young, author of the novels Dancing Priest and A Light Shining, and Poetry at Work.

__________________________

“I require all our incoming poetry students—in the MFA I direct—to buy and read this book.”

—Jeanetta Calhoun Mish

- Essays: Benjamin Myers Takes on Ambiguity and Belonging - February 4, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Louis MacNeice and “Autumn Journal” - January 30, 2025

- “What Remains: The Collected Poems of Hannah Arendt” - January 28, 2025

Maureen says

It helps to read these poems aloud, to find the places where punctuation might normally appear; I find their clarity comes through more easily. (Something interesting happens, too, when you read them from the last line up.)

I like “barricade” as a metaphor; its possibilities lend themselves to creating the poem’s structure as well as taking it down.

Glynn says

There are those who argue that all poetry should be read aloud — and if it doesn’t work when read aloud, it’s not poetry. And that’s a good point about the use of “barricade.” Thanks for the comment, Maureen.

Bethany R. says

I appreciate these poetry collection posts. They help me along as I explore a poetic voice or structure that’s new to me. Yes, Maureen, I found myself getting farther into “Thimblerigger” the more times I read it outloud. What a fascinating and original piece.

Glynn says

Bethany, thanks for the comment. It is an original piece of work, and it does require focused reading. But I found it well worth the effort.

Michael says

If anyone spoke like this in real life with incomplete thoughts or incomplete sentences you would think they didn’t know how to speak or had a problem expressing themselves. At the very least you couldn’t hold a conversation with them because their is no way to connect with them; yet because he wrote it down and made a book of it you think this is really art? I have to respectfully disagree. You can’t read a person’s mind or intentions and with this poetry it’s just the same, there is no real understanding. I’m not sure how this connects with you; are you telling me you KNOW what he’s trying to say here? Broken walls are up. Finished what it started. Chopped celery not words.

L. L. Barkat says

Michael, such an interesting point and fun to consider.

I think that the best dialog (in fiction) often comes in fragments (unnatural dialog tends to be full sentences and it sounds stilted). Poetry, of course, is already often in fragments, so this pushes the boundaries of the fragment (whether or not it does a good job at this is up for discussion).

Dialog in life often comes with stops and starts. Few sentences get completed without an interrupting gesture, a word from the other, or even a change in the flow of one’s own words.

So I’m thinking now… how much sentence completion do we need, to extract meaning? What kind of meanings are extracted where there are gaps or walls? At what point can we say a thought is complete?

Just thinking, questioning. Thanks for the inspiration 🙂

Glynn says

Michael – thanks for the comment. It’s a difficult poem to read — and to speak aloud. What it prompted me to do was pay attention to the images it presents — hiding a coin, a table collapsing from the pressure of hands placed upon it, Black Friday, a ticket (the lottery?) that pays nothing, the brightness of the west (the direction of the setting sun), a disappearing door (suggesting no escape), and the siren. This leads me to consider the end of things, or at least the end of things as we know them and understand them. Dystopia is a common theme in literature and film these days.