There’s no particular form or beauty to draw one’s eye to the old brick building that sits at the edge of Circle Drive. No stainless steel or glass architecture or even interesting sculptures on the grounds. You have to know it’s there, down just a tad from the Beaumont Tower and across from the Red Cedar River and Main Library. The Science and Culture Museum at Michigan State University, established in 1857, is one of the oldest museums in the Midwest and the first in Michigan to become a Smithsonian affiliate in 2001. Its mission is to understand, interpret, and respect natural and cultural diversity.

I’m a native Michigander. I got my BSN at MSU, only 25 miles from where I live now. Still, this is only my second visit to the museum—ever. I bring my husband and Grace, our oldest granddaughter, along with me.

After laughing at how fat the campus brown squirrels are in January, we enter the building and begin on the top floor, which seems an odd place to display dinosaur and elephant skeletons. “I’d have placed those exhibits in the basement, ” I say, but then I remember bare bones weigh much less than the bulk they have to support.

We spend some time studying dioramas of seven of the major North and Central America habitats and learn about the diversity of deer designed to live in each, from the small mazama to the bull moose. None of them would likely live well where they don’t belong. We also learn that when Michigan was a young territory and market hunting was legal, deer skins or whole deer were used as money. A deer carcass was worth a dollar, and that’s how a dollar bill became known as a “buck.”

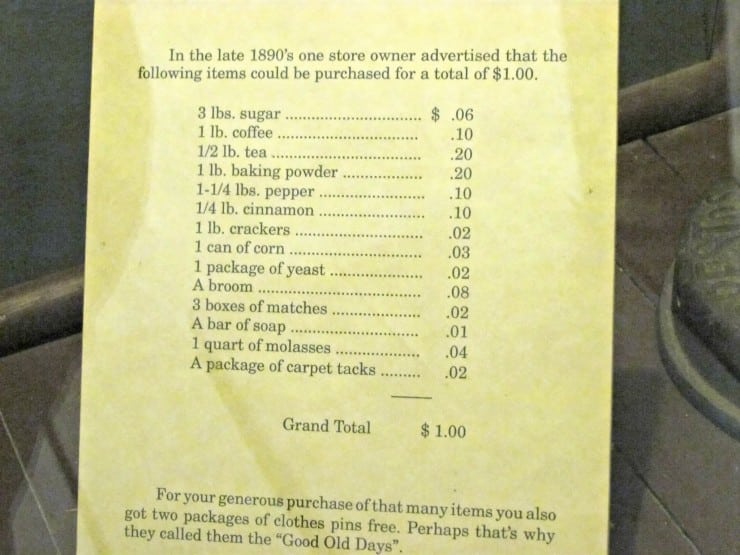

In the 1890’s, a buck could buy you most of your kitchen staples, plus some clothes pins for free.

What a buck would buy you in 1890

The Heritage Gallery currently houses an exhibit called “Up Cloche: Fashion, Feminism, Modernity, ” and I linger here. I learn a cloche was a bell-shaped, head-hugging hat and was a symbol of women’s rising political and social power in the 1920s. (Ironically, its minimal design led to the precipitous decline of professional milliners who found themselves likely to be slapping simple hats together in a factory.)

The cloche framed women’s new freedoms and new Art Deco fashions, bobbed hair and painted cupid-bow lips. The women who wore them were often known as flappers. While I wondered if that was because they were creating a societal or cultural “flap” by defying traditions, it turns out the term “flapper” originated in Great Britain when women wore rubber galoshes they left open to flap when they walked. Like their galoshes, flappers were often considered “loose” in many ways.

The head-hugging hats and bobbed hair made the hatpin obsolete except for decorative purposes, but that didn’t stop Michigan state senator Joseph Bahorski of Detroit from introducing a bill that redefined any hatpin longer than 10 inches as a concealed weapon. One wonders why he chose 10 inches. I’m thinking I wouldn’t want to come face-to-face with someone wielding a weaponized hatpin even half that long.

Across the way, in the Main Gallery, hang several quilts from Southwest China. Because I used to quilt, I’m particularly enamored with how these colorful pieced and appliqued patterns help piece together the cultural heritage of the Chinese people, and intrigued at the way the threads of the past can patch holes in the present.

Another exhibit shares the work of an Odawa quill worker who uses undyed porcupine quills, birch bark, and sweet grass to create beautiful boxes. (I don’t know where an artist goes to find quills, but I read that porcupines shed them, and that one porcupine can provide thirty to forty thousand.) Since my granddaughter Lillee’s daddy is Odawa, I’m pleased to learn more about her heritage in the stories and photos displayed.

My great-great grandfather passed down a “woody” heritage to me (I may even have sawdust in my veins), so the Michigan lumbering display particularly interests me. There, I find a little poetry.

I am a jolly lumberman, the pinewood

Is my home.

Like many other fellows—from camp to

camp I roam.

On many raging rivers, I’ve been

throughout this land.

But now I’m on the Manistee, with a

peavey in my hand.

From “The Manistee River Song, ” by Ole F. Nelson, at Sherman, MI in 1880

It reminds me of Grandpa Baxter’s poem:

Make me a grave on a sunny slope

A pine tree at my head.

A fit place for a shanty boy

To lie when he is dead.

Peel off the bark, hew down the sap,

And there mark well these lines,

“Here lies an old-time shanty boy

From the harvest of the pines.

From “The Harvest of the Pine” by James G. Baxter

Lumber harvested in Michigan in the nineteenth century was over a billion dollars more valuable than the gold of the California Gold Rush, we discover. Michigan trees even helped to rebuild Chicago. Unfortunately, there was not an endless supply, and only 49 acres of old growth pines remain in Hartwick Pines State Park, a reminder of the importance to restore what we use up.

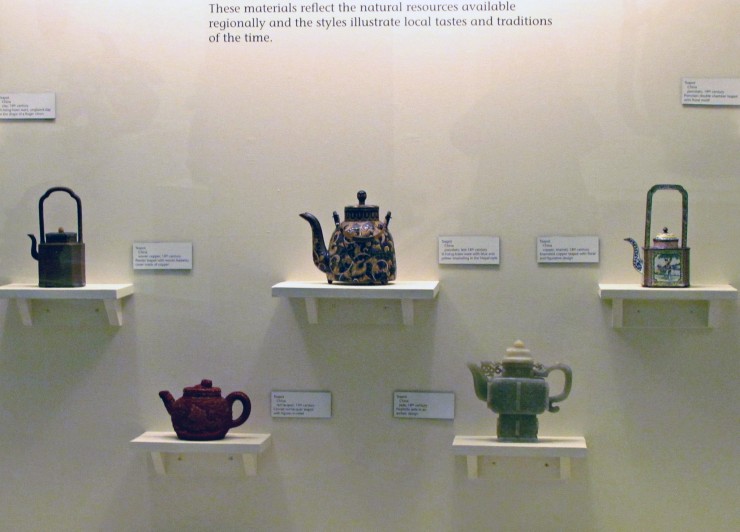

In the Hall of Cultures, a display uses teapots to illustrate the idea that culture is adaptive, diverse, dynamic, and symbolic. Their sizes, shapes, materials, decorations, and uses help us learn about the cultures that used and use them, we’re told. I have a sudden craving for tea and cinnamon toast in the Mischief Café.

On the ground floor, a collection explores the effect work has on us and how we affect our work. “Iron Hulls and Turbulent Waters” tells a story of Great Lakes shipping through black and white photos of ore boats and dock workers. There’s a replica of the S.S. Edmund Fitzgerald, the largest ship ever to sink on the Great Lakes. It went down on November 10, 1975, and was found in two pieces at the bottom of Lake Superior. Gordon Lightfoot sang about it in “The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald.” Prior to that, the Carl D. Bradley went down in Lake Michigan in 1958 and the Daniel J. Morrell sank in Lake Huron in 1966.

It seems appropriate that I end my visit with the discovery of a new-to-me Michigan poet, Cindy Hunter Morgan, who shares poignant words about both of these shipwrecks. When we return home, I scour the Internet for more of Morgan’s poetry and connect myself to The Michigan Poet. I remind myself of what beauty can be discovered behind old doors. And I write down the date of the Chocolate Party coming up next month to benefit the museum.

Featured photo by Judit Klein, Creative Commons via Flickr. Post and museum photos by Sandra Heska King.

Browse more Regional Tours

Browse more Museums

__________________________

“I require all our incoming poetry students—in the MFA I direct—to buy and read this book.”

—Jeanetta Calhoun Mish

- 50 States of Generosity: Iowa - April 7, 2025

- 50 States of Generosity: Montana - January 27, 2025

- 50 States of Generosity: Idaho - December 16, 2024

Donna says

Sandra, of course I love the teapots! Thanks so much for the wonderful tour, and all of the word origins… it’s so interesting to learn where commonly used words come from. The buck! Love that. 🙂 I feel like I’ve seen a bit of Michigan now, thanks to your top to bottome tour. 🙂 Maybe I’ll see it in person some day. I’ll look for the cloche collection, and you know – I never would have guessed in a million years that flapper had to do with rain gollashes!

Sandra Heska King says

I couldn’t believe the teapots! How perfect, yes? I wonder what fun stuff I’ve missed over the years by ignoring what’s right under my nose. I totally loved the hats. 🙂

Maureen says

Lots to like: great hats, marvelous handwork, beautiful tea pots. Thank you for allowing us to tour with you.

Sandra Heska King says

Thanks, Maureen. There was so much other stuff I wish I could have shared. I stayed a long time contemplating an Aztec diorama that included a pyramid sacrifice taking place (ugh) and several creative displays from different cultures. I’m glad I got to bring you along. 🙂

Patricia @ Pollywog Creek says

I love this, Sandra. The “buck”, the hats and pins, and the box made of quills are my favorites. As the mother of a harbor pilot, the sinking of large ships is a sad reminder of his dangerous occupation.

I’m inspired now — wondering where I’d find the closest museum.

Sandra Heska King says

I know, right? I’m on a mission to find things I’ve missed. I think knowing I was going to write about this visit made me way more attentive, too. 🙂

Jody Collins says

Sandra, what a fascinating tour and history lesson. Now I know why a dollar is called ‘buck’. I love trivia like that.

What a joy to have such a treasure so close to home….

Sandra Heska King says

There are several museums and such nearby. Silly me for not paying attention. And I never knew that about a buck either.

L. L. Barkat says

I think you should be a museum journalist. 😉

Seriously, I loved this. You could go on museum-writing tour. 🙂

Sandra Heska King says

Thanks. Wait. Seriously? There is such a thing? This was fun–hard, but fun. I’d do it. But I’d need LW to clean things up. 😀

L. L. Barkat says

If you do it, there will be such a thing 🙂 And you already have a set of readers waiting for you when you get home.

Sandra Heska King says

Well, I’ve learned a lot from the museum journalists who’ve posted here before. But this could be fun. Maybe I need to make a museum bucket list. 🙂

Rick Maxson says

I read this, then read it again. It was a fascinating tour. The writing was marvelous, the photographs as well. The whole piece made me want to go there. I actually love the architecture of the building. Much more interesting than walls of reflecting glass. Well done!

Sandra Heska King says

Thanks so much, Rick. The only way to tell it’s really a museum is by the letters over the double doors. The building kind of reminds me of my old brick junior high/high school.

Laura Brown says

Sandra, you have this curiosity that is both practical and fearless. I loved reading this and seeing the museum through your words and photos. The hats! The teapots! Even the little poems.

L.L. is right. Go to more museums, see them, and tell us about them.

One question: What’s a peavey?

Sandra Heska King says

Practical and fearless? Now that makes me smile!

A peavey was (is?) a logger’s bestest tool–a long pole with a spikey end used to roll, hook and control logs. River drivers rode the logs as they floated downriver and used their peaveys to keep things moving and not jam up. It was an adventure–and a very dangerous job.