Every time I hear someone say I don’t like poetry, or I’m not a poetry person, I think the opposite is true. I believe everyone is a poetry person. Poetry is just a form of storytelling, and we’re born to tell stories.

A few weeks ago at Bistro de l’Arte in Brasov, Romania, I was rearranging the order of my manuscript, yet again, when a little girl wandered over to me, looked at my laptop screen, and rested her chin on my table. I asked her in Romanian if she knew poetry. Yes, yes, she said, I know poetry. I like it. Kids get it.

I once read Elizabeth Bishop’s The Fish to a ten-year-old girl. We were talking about how a simple moment can be a poem. I told her I was going to read one that was just this. I wasn’t sure if the length of it would hold her attention—Bishop poems are so patiently written, and reading them requires patience. (I often tell my students that her poems are like beer—sometimes an acquired taste.) Also, based on my own experience googling several of the boat terms toward the poem’s end the first time I read it—bailer, thwarts, gunnels—I knew she wouldn’t understand all of the vocabulary.

“I caught a tremendous fish…”

As I read it, she sat quietly, looking from one object in the apartment to another. I couldn’t read her face, but she didn’t look particularly interested.

“…And I let the fish go.”

I looked at my young friend, who sat without talking for a moment. You know what? she said. You’re right. It’s about something so simple, it’s like it’s not even worth it. Oh. I probably shouldn’t have, but I felt a little bummed out. I knew she was just a kid, that this was just a poem—But then, she continued, she makes it worth it.

The moral of this moment? Children teach us about poetry.

Somewhere along the way—usually around high school, sometimes college—a lot of students (mainly the ones who aren’t writing poems) become intimidated by poetry. They associate it with archaic grammar, rhymes, rigid form. It has to be understood one specific way, becomes something that can’t be penetrated. Before beginning a writing exercise for a Mass Poetry Student Day of Poetry one morning, a teenager raised his hand and asked me, Do we just write, or do we write in the form of a poem?

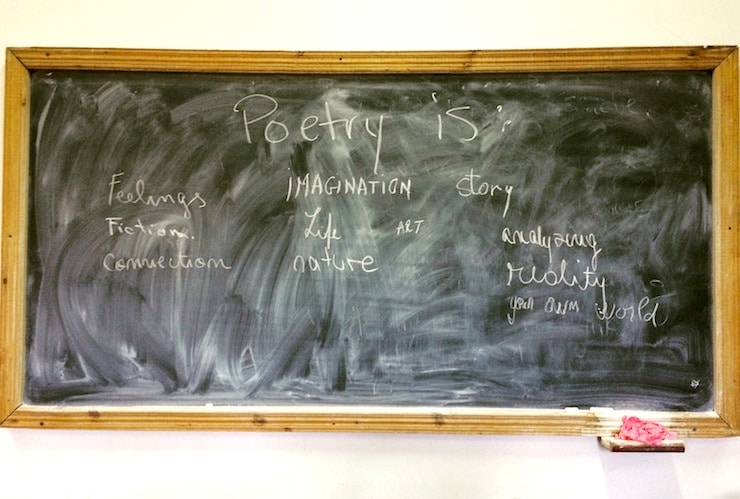

The good thing is, returning to poetry is just like trying to use a second language you haven’t spoken or heard in a while: its essence remains intact. It’s all about getting started. I write Poetry is… on the board (I got this idea from my good friend, poet Derek JG Williams). Each student comes up and writes a word. Fear, feelings, imagination, story, fiction, life, art, analyzing, communication, nature, reality, honesty, mystery, melody, limitless, unknown, dreams, freedom, love, hidden. Sometimes unlearning is the simple act of realizing again what you once instinctively felt.

I like to begin each semester with an in-class guided writing exercise on memory. I have the students think of a moment in which their perceptions of themselves, the world, a person, changed. Another person must be present in this memory. I tell them to use specific details (and that detailed doesn’t necessarily mean more words) and not to worry about complete sentences. 20 lines max. I give a series of directions while they write, and I interrupt them constantly with these instructions—because this is how memory works: seemingly unrelated moments are triggered by senses, place, story. The whole thing takes less than 10 minutes.

My current version of this exercise, simplified, is:

1. Write the place of this memory.

2. Focus, zoom in on the thing that stands out, what is happening.

3. Who are you with?

4. This person reminds you of someone, something. Relate this person to a person, image, object, sense, place, etc.

5. Change a detail of this memory (because memory is a narrative, and narratives can be altered).

6. You hear something.

7. Someone says something.

8. Change another detail.

9. You do something. What do you do?

10. Zoom in on what stands out.

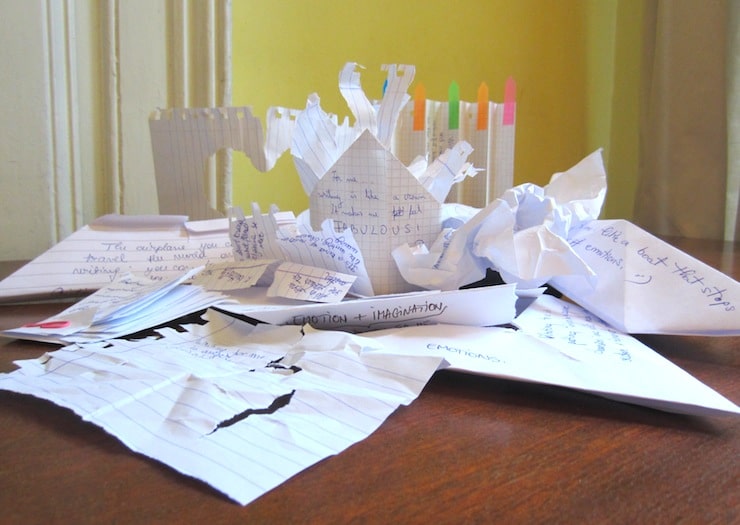

Before they know it, they’ve drafted a poem of sorts that has place, metaphor/simile, character, dialogue, the senses, action, image. And, most importantly, something is at stake. Speaking of stake, I mentioned in Poetry at Stake that I stabbed a poem with a mechanical pencil and tore the page to demonstrate at stake to my creative writing students in Brașov. Yesterday, my penultimate class of the semester, I decided to take this exercise one step further. I had everyone take out a sheet of paper. Think about what writing means to you now, what it represents. I told them to do something, anything, to their sheet of paper. I immediately heard a page being crumpled into a ball. Without hesitation they each knew exactly what to do. I participated as well. I poked a near-perfect hole with a pencil through the middle of a blank page.

When everyone was done, I told them to turn their creation into words. I went first. I told them that writing, to me, is like looking through this small hole in the page at a distant object—first with one eye, then the other—the process of discovering your dominant eye over and over again.

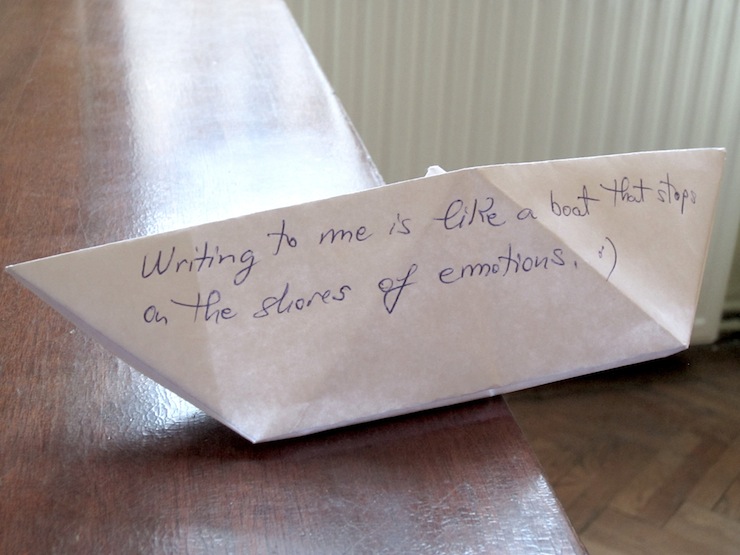

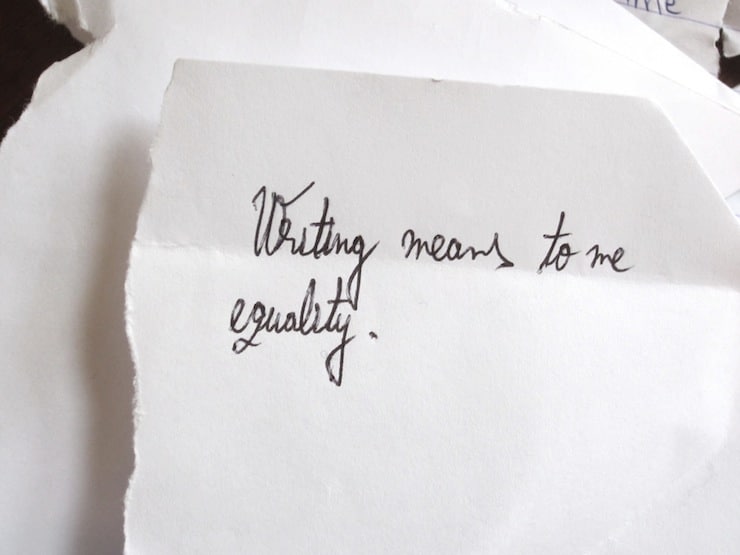

Their turn: equality, sadness, a boat that stops at the shores of emotions, frustration, many fragments put together to form something magic, a crown that makes me feel fabulous, a flower or a tree, an airplane, something useless that becomes beautiful, a butterfly on the way from one flower to another.

Finally, they are poetry people again. Finally, no fear.

Featured photo by rp_photo, Creative Commons via Flickr. Post photos and article by Tara Skurtu originally appeared at Best American Poetry under the title “I Don’t Like Poetry, I’m Not a Poetry Person” and this modified reprint is used with permission.

Read Tara Skurtu’s Journey Into Poetry

Read a poem by Tara Skurtu, in Every Day Poems

__________________________

“How to Write a Poem is a classroom must-have.”

—Callie Feyen, English Teacher, Maryland

- You Are a Poetry Person—Maybe You Just Don’t Know It - January 21, 2016

- Journey into Poetry: Tara Skurtu - July 24, 2013

L. L. Barkat says

I really like how you start with the physical in that paper exercise, which is where all metaphor first begins/began anyway. We often wonder why we have “writers block.” But touching the world and shaping it can become a catalyst.

I also love the child’s response to the fish. I imagine she was questioning silently while you were reading… “Why is this lady reading me this poem? Why a fish? Where is this going?” (Would love to hear you read it aloud! 🙂 )

Megan Willome says

Amen and amen.

P.S. Love your exercise. Thanks for including the steps.

Dawn Paoletta (@breathoffaith) says

Brilliant. Beautiful. YES!

Lynne says

This is fantastic. I love the exercises you used with the children…so effective!

Donna says

This: “Sometimes unlearning is the simple act of realizing again what you once instinctively felt.”

So much power in these words.