“It is the purpose of our government to elevate the condition of men, to lift artificial burdens from all shoulders and to give everyone an unfettered start and a fair chance in the race of life.”

— President Abraham Lincoln, July 4, 1861.

On a recent Saturday in September, while the rest of Nebraska cheered on the Cornhuskers, my son Noah and I drove 40 miles south from our home in Lincoln to Homestead National Monument in Beatrice and stepped back more than 150 years in history.

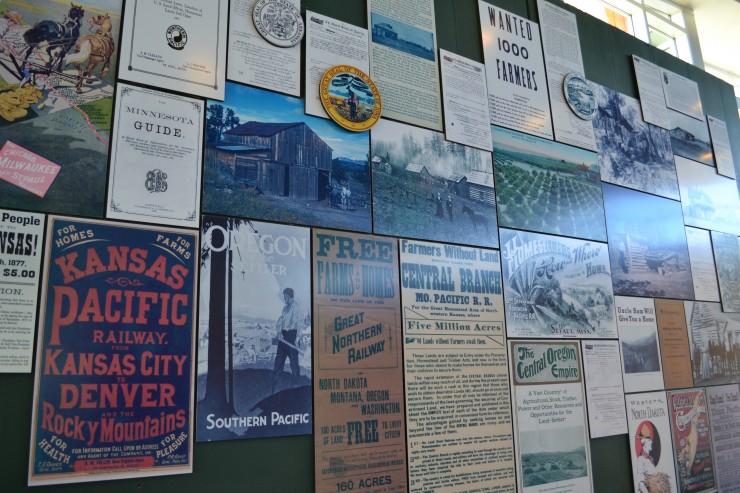

You may have studied the Homestead Act of 1862 in your middle school social studies class, and if you did, you likely read Abraham Lincoln’s words conjuring images of lurching covered wagons, humble sod houses, acres of ripening corn, a vast sky and endless land — a time of bountiful opportunity, an era of courage, exploration and wild freedom.

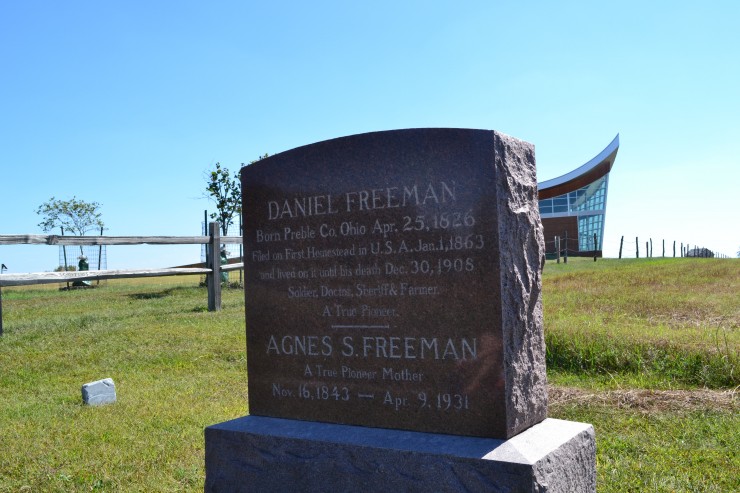

As Noah and I explored the exhibits at Homestead National Monument, we heard the stories of a few of the two million people who settled approximately 278 million acres of land over 125 years, including Daniel Freeman and Kenneth Deardoff. Freeman was a soldier, farmer, doctor, coroner and sheriff who filed his claim ten minutes after midnight on the day the Homestead Act went into effect, January 1, 1863. Homestead National Monument now sits on the site of his claim, and Freeman and his wife Agnes are buried on the property. More than 120 years later, Deardoff built a cabin in southeast Alaska, and in 1988 was the last person to receive a title to land claimed under the Homestead Act.

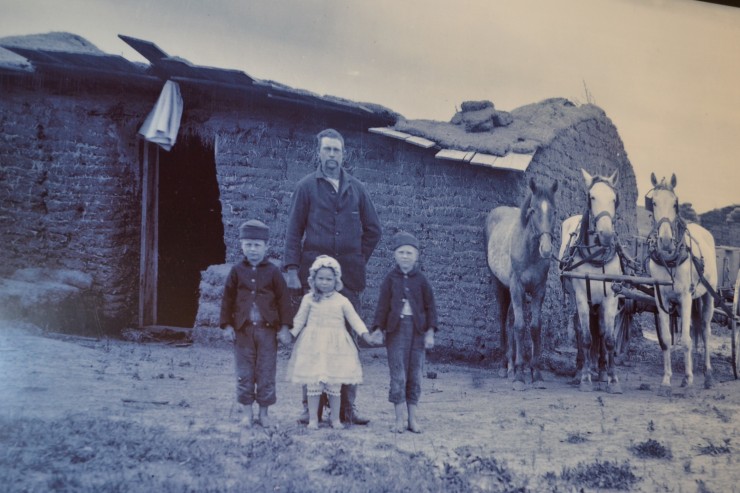

Many of the images displayed at the Monument were familiar from my middle school social studies textbook. I recalled the grainy photographs of grim-faced families seated side-by-side in front of houses that looked like grass-covered hills of dirt. I remembered reading about the devastating droughts and dust storms, the howling winds and snow drifts 20 feet deep. As I gazed at the images and read the exhibit materials, I recalled the pride and awe I’d felt when I first learned about these strong, fiercely independent pioneers who broke the wild land and slept in homes carved into the cool, dank earth.

But Homestead National Monument also highlights the largely untold story of the people harmed by westward expansion. The Monument not only commemorates the Homestead Act of 1862, it also illustrates the far-reaching effects of the Act, both on the people who arrived to stake their claim and those who were forced out as a result.

As it turns out, what I learned in middle school is only part of the American story. My text books didn’t cover the other less noble, less inspiring pages of that period in history: the story of the hundreds of thousands of American Indians who were displaced, driven from their homes with each 160-acre parcel of land signed over to a homesteader. The story of the thousands who died from illness and starvation as they walked hundreds of miles to the reservations. The story of a people who lost not only their land, but their culture and their way of life as well. While we celebrated and admired our ancestors’ quest for a “fair chance in the race of life, ” we neglected to acknowledge that not everyone was given the same fair chance.

Before we drove back to Lincoln, Noah and I walked behind the Monument building to the spot where Daniel and Agnes Freeman are buried along the edge of the tallgrass prairie. The original headstones are still there, timeworn and mottled grey, two small stone lumps barely visible above the grass. Next to them is a large, modern headstone that was clearly erected more recently, the granite polished to a sheen.

I crouched to snap a photograph and read the words engraved below their names. “Soldier, Doctor, Sheriff & Farmer. A True Pioneer, ” Daniel’s epitaph declared, and beneath it, Agnes’s inscription: “A True Pioneer Mother.”

I don’t doubt for a moment that Daniel and Agnes Freeman were true pioneers in every sense of the word — courageous, determined, smart, industrious and fierce. But as I gazed at their headstone with the prairie unfurling beyond it, I also couldn’t help but think about those whose lives were irrevocably altered to make room for the Freemans and the other homesteaders on this vast expanse of land.

Featured Photo by Kristaps Bergfelds. Creative Common license via Flickr. Post and photos by Michelle DeRusha.

Browse more on Literary Tours

__________________________

“I require all our incoming poetry students—in the MFA I direct—to buy and read this book.”

—Jeanetta Calhoun Mish

- Regional Tour: Homestead National Monument, Beatrice, Nebraska - November 13, 2015

- Making Little Free Library No. 25, 001 - November 4, 2015

- Regional Tour: North House Folk School, Grand Marais, Minnesota - August 12, 2015

Megan Willome says

Thank you, Michelle. There’s always more to the story, isn’t there? Especially when it comes to history.