We’re standing on the sidewalk outside the Hampstead Tube station north London, right on the southern edge of Hampstead Heath. We’ve taken the Tube from near our hotel in Westminster to the Embankment station, and changed to the Northern line. We find ourselves this busy Saturday morning at the major crossroads of Hampstead—the intersection of Hampstead High Street and Rosslyn Hill.

We’re waiting for John Keats.

More precisely, we’re waiting for Anita Miller, our guide for the monthly Keats Walk in Hampstead. We booked our tickets online through what is today the John Keats House (also known as the Wentworth House) in Hampstead. The tour will end at the house, but we have about two hours of walking, stopping and listening before we arrive at the house. My wife would want me to point out that it’s less a walk and more a hike—Hampstead and the heath are hilly, and some areas are more suitable for mountain goats.

Our group is eclectic, with one exception—most of the 12 of us are female. I’m one of two men, and the other looks like he’s come along at his girlfriend’s request. Our ages range from high school to Baby Boomer.

Anita Miller arrives and ticks our names off the reservation list. We’re the only Americans on the walk, and it’s a bit unusual for tourists to do this, unless they’re academics. She’s likely a little younger than I am, but she’s used to walking Hampstead, and she walks very fast. Fortunately, she’s good about waiting for stragglers. We follow her across the street and down a wide alleyway, where she explains what we will be doing, how the walk is structured, and how she will be reading from Keats’ poetry at each stop. She’ll also point out interesting historical facts along the way.

I read Keats in high school and college, and on the plane from Detroit to London Heathrow, I read a Penguin edition of his Selected Poems, which included the earliest known poem he wrote (usually dated to about 1812), “Imitation of Spencer”:

Now Morning from her orient chamber came,

And her first footsteps touch’d a verdant hill;

Crowning its lawny crest with amber flame,

Silv’ring the untainted gushes of its rill;

Which, pure from mossy beds, did down distill,

And after parting beds of simple flowers,

By many streams a little lake did fill,

Which round its marge reflected woven bowers,

And, in its middle space, a sky that never lowers.

There the king-fisher saw his plumage bright

Viewing with fish of brilliant dye below;

Whose silken fins, and golden scales’ light

Cast upward, through the waves, a ruby glow:

There saw the swan his neck of arched snow,

And oar’d himself along with majesty;

Sparkled his jetty eyes; his feet did show

Beneath the waves like Afric’s ebony,

And on his back a fay reclined voluptuously.

Ah! could I tell the wonders of an isle

That in that fairest lake had placed been,

I could e’en Dido of her grief beguile;

Or rob from aged Lear his bitter teen:

For sure so fair a place was never seen,

Of all that ever charm’d romantic eye:

It seem’d an emerald in the silver sheen

Of the bright waters; or as when on high,

Through clouds of fleecy white, laughs the coerulean sky.

And all around it dipp’d luxuriously

Slopings of verdure through the glossy tide,

Which, as it were in gentle amity,

Rippled delighted up the flowery side;

As if to glean the ruddy tears, it tried,

Which fell profusely from the rose-tree stem!

Haply it was the workings of its pride,

In strife to throw upon the shore a gem

Outvieing all the buds in Flora’s diadem.

He was 16 when he wrote that poem.

Of all of the major Romantic poets, Keats is definitely the odd man out. Shelley, Wordsworth, Byron and Coleridge were better educated. They came from a “better class” than Keats in a society that was even more class conscious then than it is now (and it is still plenty class-conscious today). They were all somewhat older, and he would die first, in 1821, although Shelly died a year after Keats and Byron two years after Shelley. Their reputations (good and bad) continued mostly intact after their deaths; Keats nearly disappeared into obscurity.

In his lifetime, he published only 54 poems; he wrote about 150 in all. Some three decades later, it would be Tennyson who began the revival of interest in Keats and his poetry. Today, he might be called the most influential of all the Romantics—you can find his influence in the poetry of the Pre-Raphaelites, Tennyson, Ezra Pound, T.S. Eliot, James Joyce, Derek Waldcott and Seamus Heaney.

Keats was born in London on Oct. 31, 1795; a few weeks later he was baptized at St. Botolph Without Bishopsgate Church, near where his parents lived and father worked as the manager of a stable owned by his father-in-law. Keats was the eldest of four children, with George, Tom, and Fanny following him. The family was well off enough that the boys were sent to Clark’s Academy in Edmonton at what is now the north London borough of Enfield for their education; it was riding his horse home from a visit to the school that Keats’ father fell and died the next day. His mother remarried (rather quickly, in fact), fought with the rest of the family, and died fairly young from consumption or tuberculosis, which was all too common at the time and would eventually claim the life of Keats’ youngest brother, Tom, as well as Keats himself.

He was apprenticed to a local doctor, but the relationship didn’t seem to work too well. He ended up working at St. Guy’s Hospital in the Southwark district of London, continuing his medical training and writing poetry (the site of the original St. Guy’s in now occupied by London’s tallest office building, known locally as “The Shard”).

While Keats had numerous city connections (Anita Miller also has a “Keats in the City” walk), it is with Hampstead that he is most closely associated. Fellow poets lived there, as did the editor who first published his poetry. Artists whom Keats associated with lived there. Keats himself would move there with his brothers. Keats and his friends would wander Hampstead Heath, talking and arguing poetry and the issues of the day. After moving into Wentworth House in Hampstead, Keats wrote five of six famous odes, including “Ode to a Nightingale.” And it would be at Wentworth House in Hampstead that Keats would realize that he was dying from the same disease that took his mother and younger brother.

Anita Miller gets our attention. Our walk is now beginning, and our first stop will be Church Row, the oldest street in Hampstead, which leads directly to our second stop, the Parish Church of St. John in Hampstead. It’s a rather unusual place to stop for a Keats walk, since the poet was an atheist and never visited the church.

During the month of November, I’m posting each week on John Keats and his poetry. Next week, we’ll continue the walk and discuss some of the “politics” surrounding Keats and his poetry.

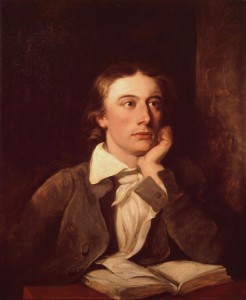

Photo by Robbie Shade, Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post by Glynn Young, author of the novels Dancing Priest and A Light Shining, and Poetry at Work.

A Month with Keats: Keats and Hampstead Heath

A Month with Keats: Poetry, Religion and Politics

A Month with Keats: A Walk into His Life

__________________________

“I require all our incoming poetry students—in the MFA I direct—to buy and read this book.”

—Jeanetta Calhoun Mish

- Poets and Poems: Sandra Marchetti and “Diorama” - April 24, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Christina Cook and “Roaming the Labyrinth” - April 22, 2025

- Longfellow’s “Paul Revere’s Ride”: Creating a National Legend - April 17, 2025

Sandra Heska King says

This is going to be great! Color me excited.

Glynn says

It was a pretty challenging walk – both for the speed and the hills! Thanks for reading the post!

Megan Willome says

What fun! It makes me happy to know there is such a thing as a Keats Walk in the world.