Sometime in the early 90s while I was an undergrad, the Career Development Department at my university introduced me to What Color Is Your Parachute, a guide to finding one’s career path by finding one’s passion. It was the same era when I took personality and gift inventories about every other month, including the one which said “garbage collector” would be a good career match for my skill set.

But I was no more passionate about waste removal than I was about fashion modeling. I was passionate about writing. And though I earned little more than minimum wage in my first professional writing position as a newspaper reporter, I believed my passion was worth pursuing.

I’m still passionate about writing in fact, and despite the growing collection of experts who now insist we should stop counseling young people to follow their passions, I’m still writing.

Why shouldn’t we follow our passions?

The “don’t follow your passion” movement started sometime around 2012. That’s the defining moment Cal Newport, author of So Good They Can’t Ignore You, highlights in a recent Business Insider article “A Steve Jobs quote perfectly sums up why passion isn’t enough for career success.” According to Newport, people had been talking about Jobs’ 2005 Stanford commencement address for years. “Your work is going to fill a large part of your life, and the only way to be truly satisfied is to do what you believe is great work. And the only way to do great work is to love what you do, ” Jobs famously told that graduating class.

But during a panel at the 2012 Democratic National Convention, Jobs biographer Walter Isaacson felt like he needed to set the record straight, to tweak the advice Jobs had given. “The important point is to not just follow your passion but something larger than yourself, ” Isaacson said. “It ain’t just about you and your damn passion.”

Newport goes on to talk about seeing a career, even a job, not just as a thing to get something from, but a place where we can give back. It’s good advice. He also says that the “follow your passion” advice can become limiting to young people who don’t feel a true calling or don’t know exactly what they want to do as a career. No passion? No problem, says Newport. “… work passionately toward the hard but worthy goal of making an impact.”

Of course the “don’t follow your passion” folks talk about career choices just as blindly as they accuse the “follow your passion” crowd of doing, as if young people don’t know how hard it is to get a job with an English major. In fact, in a January 2015 article in Inside Higher Ed, Colleen Flaherty reported that English majors are declining throughout the country. She interviewed Sarah Feeney, a senior at the University of Maryland, who followed her passion in choosing English as her major but understands why other students don’t.

But maybe you are following your passion

“I think that a large part of why we’re seeing fewer English majors, and fewer humanities majors in general, is because students are constantly told that studying a subject in the humanities will only prepare them for jobs in the fast-food or retail industry, ” Feeney said in that interview. “We need to work hard to show students that studying a subject like English can help to prepare them exponentially for the future. Studying the humanities helps you to learn to quickly analyze and understand information and to communicate ideas.”

The “don’t follow your passion” advice also seems to suffer in a way similar to the “write what you know” mantra for authors. I can know new things by giving myself different experiences and acquiring new knowledge. The same is true for passion. I can care about different things throughout my life. If nothing else, that’s what I gathered from the story about Steve Jobs.

In an earlier article Newport wrote for Fast Company, he tracked the life of Steve Jobs, saying Jobs was decidedly not passionate about technology, business, or entrepreneurism as a young man. “He instead studied Western history and dance, and dabbled in Eastern mysticism, ” Newport wrote. But as I see it, Job’s famous drop out of college and those early years in his adult life when he was dabbling in spiritual enlightenment and taking jobs as needed demonstrated he actually was just following his passion.

When, as Newport and others have noted, Jobs got his “lucky break, ” abandoned his passions, and became rich, who’s to say that he would have been prepared to take those early risks had he been off doing what was practical? Maybe those first few years of following his passions gave him the vocational flexibility and freedom to see a good deal—and develop a new passion—when the time came. Would anyone argue that Jobs was not passionate about Apple?

So we should follow our passions?

If the “don’t follow your passion” advice is a little off, should we all just go back to telling young people to follow their passions again? Maybe not. The follow-your-passion advice also has some limitations.

First, it can be biased. Back when I was trying to figure out what color my parachute was, nobody—and I mean nobody—was telling my friends who were passionate about business or education or science that they might want to major in art or literature as a “back-up.” Those friends are now psychologists and teachers and business analysts who followed their career dreams and have made a nice living for themselves.

The “follow-your-passion” folks get nervous when it comes to people like me, though, people whose passions will never translate into FTEs in corporate America or tenure-track positions or partnerships in other established institutions. We give scholarships to students who want to cure cancer, but we offer employment applications to Starbucks for those who want to write the great American novel.

Of course, humanities majors are having their day now, too. According to new statistics, philosophy majors have increasing earning power in today’s economic landscape, and The Washington Post recently reported that tech companies are snatching up liberal arts majors for their “diversity of skills and flexible critical thinking.” Newport might say, “See, I told you it’s better for them not to follow their passions.” But I would say the opposite. Following one’s passions doesn’t mean a life of poverty, and success doesn’t always look like one thing. I think today’s young people are smart enough to know that.

But that’s the second difficulty with the follow-your passion advice: it has become something of a master narrative in our culture. “Once certain stories get embedded into the culture, they become master narratives—blueprints for people to follow when structuring their own stories, for better or worse. One such blueprint is your standard “go to school, graduate, get a job, get married, have kids, ” writes Julie Beck in a recent Atlantic article called Life’s Stories. Master narratives can be helpful templates to young people, providing them with a vision for success in their lives, especially for those following their passions. But they can “stigmatize anyone who doesn’t follow them to a T, and provide unrealistic expectations of happiness for those who do.” On this point, Newport and I tend to agree.

You can both follow and work outside your passion

At its heart, the follow-your-passion advice for people of any age is not about creating self-entitled employees who will only ever seek to do what they are passionate about. It’s about giving people permission to keep caring about whatever it is that fills up their souls.

Likewise, most of us know that following our passions doesn’t always mean changing the world or creating an empire or padding our personal bank accounts. We may have to move outside of our passions to meet the needs of our community or achieve financial security. But we can still follow our passion by doing it “on the side” or for no pay at all, by coming to that thing we love prepared to work, to put in the time, and to take the risks when they come along.

Because unless you try, you’ll never know. Maybe you can change the world with your passion. Just be sure you’re wearing your parachute—whatever color it is.

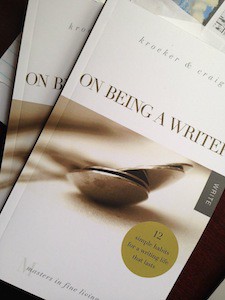

Photo by Diana Robinson, Creative Commons license via Flickr. Post by Charity Singleton Craig, co-author of On Being a Writer: 12 Simple Habits for a Writing Life that Lasts.

_______________________

Pursue a Masters in Fine Living

Let this book act as your personal coach, to explore the writing life you already have and the writing life you wish for, and close the gap between the two.

- Grammar for a Full Life Book Club: On Becoming Less Possessive - June 16, 2021

- Grammar for a Full Life Book Club: Chilling Out on the Grammar Rules - June 9, 2021

- Grammar for a Full Life Book Club: A Passive Voice - June 2, 2021

L. L. Barkat says

What a thoughtful essay. (And of course I approve of both English and Philosophy majors! 😉 ).

I have done and still do both. For I am practical and passionate, both. As much as possible, though, I try to meet my practical needs through things I can take a passionate interest in. There’s more energy to be had in that.

Your last line made me laugh aloud. Love. 🙂

Charity Singleton Craig says

Laura – I see you living that – passionate and practical at the same time, at every turn. You model that well for so many of us.

As for me, I have felt more that I am a pendulum swinging between the two … until recently, that is. I have struck a balance recently that I feel very happy with.

Donna says

Yes yes yes I love this!

Charity Singleton Craig says

Donna – Were you given one set of advice or the other when you were younger? How did that play out for you over time?

Donna says

I don’t remember getting that kind of advice. I can’t really remember anyone ever talking with me about career or college (which doesn’t mean they didn’t, but I don’t think so). My Aunt Nellie was a woman way ahead of her time. She went to college when most women didn’t. She graduated the year my father was born. At 19 she was a nurse. She continued her studies and work and became the first female principal and then superintedent of the Willard School of Nursing in NYS – so she was a very influencial figure in my life. So much so that I never thought of NOT going to college. I wound my way to Early Childhood Education, which my father thought was a crazy waste of money and maybe he was right, but this is what I chose as a life path and he learned to accept it (or at least not argue the point). I had always been fascinated with children, from a young age myself. I couldn’t help but be amazed at the way they learned, the way they said things, the way the were constantly changing. I guess I did follow my passion, though i didn’t know it at the time. I was so curious that I couldn’t get enough.

Charity Singleton Craig says

I think this is probably similar to many stories about how people choose their careers. I doubt a lot of students get any advice — or any helpful advice — and they just make choices that seem right, which have something to do with their passions. Others may look back and realize it, like you did, without being aware at the time.

Part of my desire in writing this is to remind readers that it’s not too late to follow your passions, either, whatever that may look like. You model that well, Donna.

Will Willingham says

“…as if young people don’t know how hard it is to get a job with an English major.”

Loved that line. 🙂 (Add to that, a Political Science major.)

I think what is so true here is the idea of both and neither. That one thing need not be universally and at all times true. That following one’s passion can sometimes be preceded by doing things we are less (or not at all) passionate about, or that sometimes following one passion leads us into another.

And that sometimes we just need to be patient, and nurture that passion in other ways.

Thanks, Charity. 🙂

Charity Singleton Craig says

LW – I think your take here is exactly what I wanted to explore. We can follow our passions and at the same time, or sometimes in turn, we shouldn’t follow our passions. We put a lot of pressure on young people to decide what they want to do with the rest of their lives AND become self-supportive AND follow their passions or not. I think it takes a while to figure a lot of that out.

I’m well aware, too, that this is a discussion not all people even get to participate in. For all kinds of reasons (poverty, race, geography, disability, obligation, incarceration, and others) some people just don’t have the choice about whether or not to follow their passions. Those master narratives aren’t helpful in those cases. Then what?

You can see that I still have more to say! 🙂 But in general, I at least wanted to communicate the complexity in an otherwise oversimplified topic.

Thanks for all your help with this.

L. L. Barkat says

I am really glad you brought that up, about not everyone getting to participate in such a discussion. And yet there is that little sub-text in what LW said, about somehow finding those cracks in the pavement of our lives (if that’s all our lives are presenting in terms of space and privilege) and planting something we can love there. My own mother did that. Her life was hard. 70 hour weeks at jobs no one really dreams of having. But she brought patience and beauty to the layaway desk at the version of Walmart that used to be Jamesway and to the tables at Burger King. Everyone loved my mother. They looked forward to her smile and the way she heard them and cared for every little need, as if it was the most important thing in the world. She built that into me, I believe, even though I have had far more privilege than she ever did. (And now you—or I—have got me crying.)

Charity Singleton Craig says

Laura – That’s a beautiful story. I am so thankful for stories like this. They defy the master narratives; they provide hope and vision in a different way. Often, even in the most difficult circumstances, there is a way to improve or redeem or lighten the load for ourselves or others.

Rick Maxson says

Charity, I remember a book I read years ago called, “Do What You Love, the Money Will Follow” by Marsha Sinetar. I think doing what you love is part of the key. Love is pervasive and powerful and, yet I do not subscribe to “all you need is love.” Along with love, a person needs awareness, skill, patience, curiosity, humanity, failure, and perseverance. I do subscribe to the homily: “The harder I work, the luckier I get.” But in my life I feel what served me best was not being afraid to change if what I was doing was not serving me or others well, or had grown lackluster.

I graduated with English/ Anthropology majors. Now I am a business analyst with HP (aside from what I do with TS Poetry) and thank the various methodologies from those disciplines every day for my skills in analysis. I think I always wanted to write, but as a child I didn’t know it, even though I had a neighborhood newspaper at 8 years old. I don’t know how those who know their life’s work early on know that. It seems mystical to me, even now.

I love the way your essay seems to say follow your nose rather than your passion or what someone says. I think the nose knows, if we pay attention. When what I was doing did not feel right for me, because it did not seem to be contributing in a real way, I tried to see what had to change — the whole or part.

Charity Singleton Craig says

Rick – What an interesting comment. You have captured this duality well – both sides have merit, both sides can serve us well. But like you, I subscribe to the “follow your nose” method. The more I do something, the more my nose can sniff out those kinds of things. Also, like you, I’ve made several changes in life. I think those were all good, or at least mostly good.

Thanks for your insight.

Amy hinkelman says

Charity,

I enjoyed this though-provoking article. Indeed, you present a realistic portrait of what it means to follow your passion. Often I think it comes down to a question of how much risk you are comfortable taking and how important financial renumeration is to your plan.

You inclusion of the fact that passions need not be your primary wage job. “On the side” can be a critical step in the process. Doing your job with passion, for something greater than yourself will provide an increased sense of fulfillment.

The humanities have dwindled as higher percentages of Americans seek higher education. The more they see it as to tool to increase earning potential the higher the likelihood that they will move into fields that pay more.

It is tragic that our culture values the humanities so poorly, but throughout history this does tend to be the pattern. In practical terms those who follow their passions are really committed to the field. The deficit left by those who would have contributed greatly to a field, if they had only been allowed a bit more opportunity, is an invisible and unquantifiable loss for us all.

Thank you for sharing your insight.

God Bless You!

Amy

Charity Singleton Craig says

Amy – I was especially struck by that last part of your comment — about what we as a society miss out on when people are not able or willing to follow their passions. I hadn’t thought about it in quite those terms. That is striking. Makes me want to do everything I can to make it possible for others to follow their passions.

As a side note to that, then, might be a discussion of sustainability of the arts, literature, and other humanities pursuits that don’t pay well. Because economics is spread throughout the subtext of this conversation.

Thanks for pushing me to think more deeply about this.

Jody Lee Collins says

What a thoughtful discussion…..loved this line, “It’s about giving people permission to keep caring about whatever it is that fills up their souls.”

You have to do what fills up your souls, even if, ESPECIALLY if it’s on the side. My son has a degree in Social Work and a minor in ministry and worship from an Oregon Seminary. He dreamed of going into ministry and leading worship but has to provide for his family, which includes 5 children, so he’s worked at grocery chain stores (5 years) and currently works as an Acct. Exec. (commission only) at a Christian radio station.

They are very close to the poverty line because his passions don’t pay well, but he still holds them…And the world is a better place–his children are a great part of that–because of his heart.

I am one of those Liberal Studies majors with a 5th year teaching credential and I’m grateful for the all around education I received.

But at the end of the day, although teaching may be my vocation, my passion is still people and words…..

Yep, it’s a complicated world. Thanks for tackling it, Ms. Charity.

Charity Singleton Craig says

Jody – You bring up another interesting economic piece of this puzzle: the fact that some people are willing to go ahead and follow their passions even if it means not making much money. They don’t wait for the windfall not do they just move on to something else that pays. They patch it together. I read a recent Atlantic article about our “gig” economy, and how more and more people are living this way. I could see how some would argue that this creates a less stable economy, when people don’t have full-time positions with paid benefits. At the same time, if people are doing good work and providing for themselves and are happier, isn’t that better than a higher GDP?

Thanks for talking through this with me.