History was never my favorite subject. But reading a few book paragraphs about something that happened before I was born, many states away, is different from living where something happened and is still discussed and analyzed. So after living most of my adult life in central Arkansas, I finally toured the Little Rock Central High School National Historic Site.

The site has a visitor center staffed partly by National Park Service rangers. National historic sites exist to interpret history, and there’s a reason the rangers are also called interpreters. I’ve taken the tour with two rangers. Each highlighted some things the other didn’t even mention.

In the fall of 1957, the Little Rock School District began desegregation with nine black students at Little Rock Central High School. The first day, they didn’t even make it into the school; they were kept out by the Arkansas National Guard, under orders of governor Orval Faubus. (One interpreter noted that in holding the line against blacks, those troops also kept out some employees—cafeteria workers and janitors.)

Nineteen days later, they started school, but a gathering mob got so menacing that school officials had them whisked away early, hidden under blankets in the back seats of police cruisers. Two days later, they finally completed their first day of school at Central. President Dwight Eisenhower had sent in troops from the 101st Airborne—the same infantry unit that helped storm the beaches at Normandy and drive back the Germans at the Battle of the Bulge—to escort the students in.

The more experienced ranger asked us questions to make us think. And, altogether, the tour and the visitor center displays will have you considering…

1. Clothing and school supplies

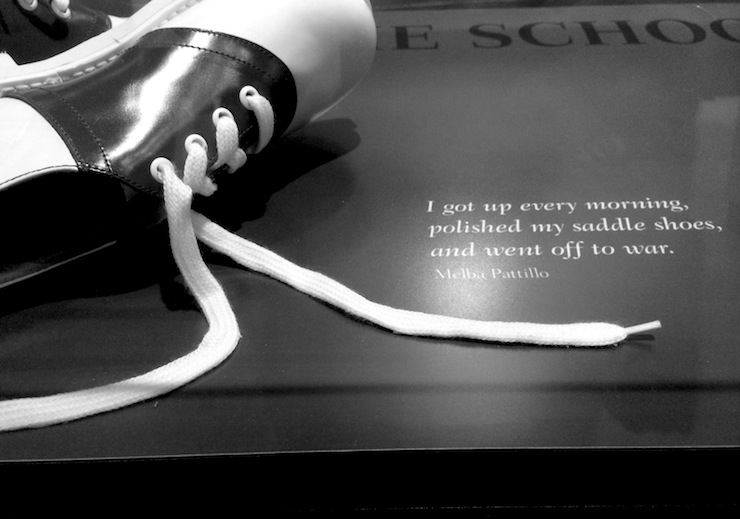

A doll-sized dress replica in a display case in the high school foyer and a pair of saddle shoes in the visitor center serve as reminders that, whether routine or historic, the first day of school is still the first day of school, with its usual anticipation. Elizabeth Eckford sewed her first-day-of-school skirt herself, and laid it out the night before. Melba Patillo shined her saddle shoes. Ernest Green wore a pencil behind his ear.

People spat on Eckford’s clothing that day. Patillo’s saddle shoes became her combat boots, as she later wrote in her journal, “I got up every morning, polished my saddle shoes, and went off to war.” Green’s jaunty pencil was a sign of the responsibility he felt to succeed as the only senior. He graduated the following spring, and a young Martin Luther King sat with his family.

2. Decisions

The perfunctory detail is the Supreme Court’s 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision that “separate but equal” public education was unconstitutional. But the decision that wows tourgoers (and left me privately thinking, could I do that? Would I let my child do that?) is the decision those students made.

Their first decision was an easy yes or no: Who wants to go to Central? Roughly 150 to 180 black students volunteered, some without discussing it with their parents. Sorting for excellent grades and spotless behavior whittled that list to 17 students, who were given a much harder decision to make: You can’t participate in any extracurricular activities. No sports, no choir, no band, no student council. You can’t even attend a football game. You can’t retaliate if you’re teased or taunted. Ten of them—many already active in sports or band or student council at their schools—said yes.

3. Civic pride (and prejudice)

When the school was built in 1927, it was the largest, most expensive high school in the U.S., as well as the most beautiful, according to the American Institute of Architects; 20, 000 people came to its opening. Its auditorium was used for concerts and other public performances. That’s one reason some whites didn’t want black kids going there, even though the neighborhood was already racially integrated.

4. Images and faces

You probably know two of them: Elizabeth Eckford, the black girl in sunglasses and carrying schoolbooks, walking with what looks like stoic courage but might also be shellshocked fear, and Hazel Bryan, the white girl behind her, shouting with what looks like hate but might be getting caught up in the moment, the cheers of “2-4-6-8, we don’t want to integrate!”

Other faces are just as riveting, in the photographs and newsreels displayed throughout the center. The innocence of the students. The fury of the segregationists. The fear on the faces of some of those National Guardsmen, not much older than the students.

5. Telephones and voices

The Mobil filling station across the street from the school became a command post for out-of-town journalists, because it had a pay phone they could use to file their stories. A drugstore across the street at the other end of the school had a pay phone, too, and Eckford headed there to call her mother, but someone locked the door and flipped the CLOSED sign in her face.

Throughout the visitor center, you can lift an old-timey black handset, press a button and hear the voices of the Little Rock Nine talking about the reasons they wanted to attend Central High, and what life has been like since.

Gloria Ray wanted to be a doctor, and Central had science labs. The sister of Minnijean Brown noticed something Central didn’t have that their all-black high school did: laundry class. She realized that class was like vo-tech for a future as a domestic servant.

Terrence Roberts tells about the white guy who stopped him in an airport years later and said they were in the same gym glass, the site of some of the severest harassment. The man told Roberts he had stood by silent. He felt bad that he didn’t step in and help. “It would have been great had he come to that realization earlier, ” Roberts said.

6. Mobs and order

How do they form? What is it about being in a group that emboldens people to behave badly? What’s the tipping point between respecting forces of order (like the 101st Airborne) and disobeying them (as the crowd did the day the city police force was in charge)?

It happened in classrooms, too. Roberts also tells of an English teacher who turned a blind eye to mistreatment, and a math teacher who firmly established her classroom as a safe place by announcing, “We are here to study algebra. Anything else will land you in the principal’s office.”

7. Memes

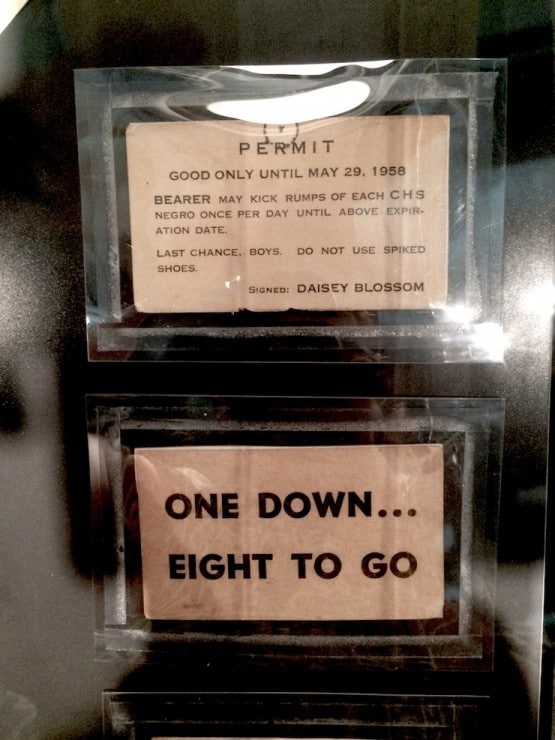

The Internet didn’t exist yet, let alone Facebook, but people had a way of spreading ideas: Printing them on wallet-sized cards. After one of the nine was suspended from the school, cards were circulated saying “ONE DOWN … EIGHT TO GO.”

8. Politics

The tussle between Faubus and President Eisenhower was one dot in the timeline of a perennial struggle in our country, between the federal government and the powers granted to states. But that’s not the only political issue involved here.

Governor Faubus talked on TV about why he was calling out the National Guard. He said it was to keep order, because he feared a mob. But it’s possible to hear his words as a tacit invitation to segregationists to come to Little Rock and form that very mob.

9. Acknowledge

There’s another photograph of Elizabeth Eckford and Hazel Bryan, all smiles side by side in front of the school, taken by the same photographer 40 years later. Bryan had long since apologized. The pair even became friends for a while. But they haven’t talked in years. Eckford asked that the bookstore not sell a print of that reunion photo anymore without a sticker on it with her words: “True reconciliation can occur only when we honestly acknowledge our painful, but shared, past.”

Cover photo by Kendra Miller, Creative Commons license via Flickr. Museum photos by the author. Post by Laura Lynn Brown, publisher of makesyoumom.com and author of Everything that Makes You Mom.

Browse Literary Tours

Browse Regional Tours

__________________

Subscribe to our free weekly newsletter.

We’ll make your Saturdays happy with a regular delivery of the best in poetry and poetic things.

Need a little convincing? Enjoy a free sample.

- Pandemic Journal: An Entry on Pencil Balancing - August 4, 2020

- Between Friends: Wordplay and Other Playful Bonds - July 25, 2019

- The Power of Curiosity: “Can I Touch Your Hair?” by Irene Latham & Charles Waters - May 29, 2019

Sandra Heska King says

Wow, Laura. That’s all I’ve got to say.

And that last line by Eckford… word.

Laura Brown says

Indeed.

L. L. Barkat says

I am curious if the museum organized by these topics (I suppose at least somewhat, yes?), or if you decided to organize your experience by these topics. Either way, I think it’s a provoking way to break it down, as a person sees just how complex the dynamics are (even if they take simple parts of life we take for granted into their framework).

This has me thinking… if a person wants to work to turn a situation around, or to frame or reframe any situation at all, it takes multiple inroads to accomplish it. Some can be easier to tackle first, and I would assume those would be great places to start in creating change.

Hmmmm.

(I’ll probably be back later with more thoughts. These are initial ones.)

Laura Brown says

This is my own organizational device, with nine because of the Nine. I could’ve done 15 or 20. The center’s organizational structure is different. One I could have added that the tour and the center’s displays both highlight is the role of the media in making this a national story and carrying the realities of segregation in the South to TVs and breakfast tables across the U.S.

Large-scale change takes multiple inroads, yes. But I think the small individual gesture is powerful too. To risk friendship, for example.

I’d like to hear your further thoughts when you have them.

L. L. Barkat says

Okay, then I very much like that you organized the retelling of the experience in this way. I think it causes a person (at least me) to think about some of the aspects of a situation like this one from many angles—and, like I said before, to consider what it takes to really effect change.

One of the things I wondered about (not that we’ll ever know) is if when that girl saw that picture of herself so filled with hatred… if when she saw how ugly and frightening she could be… if that maybe was a mirror that caused her to make amends. It is not easy to find mirrors of ourselves. If it’s mirrors others hold up in words, we can often write that off to their own “over-sensitivity” or “agenda.” But a visual mirror. How hard to deny.

So… there is need for art, photography, and poets who can make pictures with words to help us, as Blake says “see ourselves as others see us.”

The meme cards are examples of “bad poetry.” Not so much in structure, but in the way we can misuse poetic type language to oppress others. The world needs good poets, it does.

Laura Brown says

There’s a whole book about what happened between the two after that photograph. Here’s an article by its author (also linked to in the text):

http://www.slate.com/articles/news_and_politics/history_lesson/2011/10/elizabeth_and_hazel_what_happened_to_the_two_girls_in_the_most_f.single.html

Kelly says

Great story Laura. I recognized the first picture of Eckford. We had a lot in common. I also sewed my own clothes and wore saddle oxfords. They were my cheerleading shoes. Polishing them was my favorite past time. Of course I was born in 1959. By the time I got to high school things were very different. Our school was fully integrated and we didn’t even think about the struggke really. We were all standing side by side fighting the authorities for a smoking lounge where the afros and long hairs were talking about love and getting high. I did go to Middle School in Santa Monica, CA where we left our midwestern catholic grade school for a year due to my dad’s work. Talk about culture shock! Our school bus was hit with bottles as we drove away some days…always a fight between the races. There was an apparent pecking order… Black. Hispanic.

White. Asian. It didn’t take me long to figure it out. I was attacked by a gang of “chicanos” (sp? That is what they were called) out in the yard between the gym and the main campus. They cornered me up against the 7 foot chain link fence and started pushing, shoving and smacking me. All because I told them to stop making fun of my friend’s breasts in gym because they were making her cry. I was terrified until a bunch of my black classmates came to my rescue. They put an end to it all. They surrounded me on every side and walked me to class. I was so proud to be in their company and so relieved.

Laura Brown says

Wow. Thank you for sharing your story, Kelly.